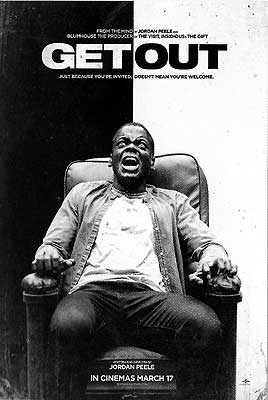

Get Out (2017) ***˝

Get Out (2017) ***˝

I enjoyed “Key & Peele” more than any other sketch comedy show since “The Kids in the Hall” went off the air in 1995. A bitingly satirical and unapologetically absurdist look at race and culture through the eyes of two nerds of mixed parentage, it was the perfect thing of its kind for the Obama era. Also, “Key & Peele” further earned my affection by frequently using horror, sci-fi, and fantasy premises as the jumping-off points for its skits. To name just a few, there was the bit about the evil but cancer-ridden child who enlists the Make a Wish Foundation to give him a chance destroy an idealistic doctor’s faith in humanity; the sketch positing Jaleel White as a diabolical genius with mind-control powers; and the simultaneously breezy and pitch-dark segment in which a man being brutally arrested on trumped-up disorderly conduct charges hallucinates himself into a 30’s-style escapist musical number about the black utopia of Negrotown. So when I learned that Jordan Peele was making his debut as a feature film director with a riff on The Stepford Wives, in which affluent white liberals hatch a nefarious scheme to remake black folks on a model more to their liking, I knew at once where ten of my dollars and 100 of my minutes would be going. Get Out does not disappoint. It occasionally flubs the balance between horror and humor (naturally a horror film written and directed by a comedian would shoot for a few laughs too, right?), but there’s no denying its effectiveness in both modes, nor gainsaying its discomfiting power as satire.

A twenty-something black guy who will later be identified for us as Andre Hayworth (The Purge: Anarchy’s Lakeith Stanfield) is walking down the street at night in a tony suburban neighborhood, talking on his cell phone and visibly feeling out of place. Soon he notices that a white sports car is tracking him, creeping along a dozen or so yards behind him and carefully matching his pace. No, that’s definitely not good— like maybe even George Zimmerman/Trayvon Martin not good. Andre tries a couple course changes, but each time the car speeds up to cut him off. No, not good at all. Hayworth begins talking as the driver gets out of his car, groping for that elusive spot on the graph where “not looking for trouble” and “not looking like a victim” meet. I don’t like his chances. Also— is that guy getting out of the car wearing a greathelm?! He is! He’s wearing a fucking greathelm! I can only hope there’s a witness peering out from one of those darkened bay windows as the helmeted man seizes Andre in a headlock and stuffs him into the trunk, and that tomorrow’s evening newspaper will run a story about the Medieval Times Maniac. Not that it’ll help Andre any…

Meanwhile in Brooklyn, another young black dude is contemplating a trip to the burbs with trepidation bordering on dread. That would be professional art photographer Chris Washington (Daniel Kaluuya), who is about to spend the weekend getting to know the family of his new-ish girlfriend, Rose Armitage (Allison Williams). A lot of guys would find that prospect intimidating, but it’s even more fraught for Chris because Rose is white. Not only that, but she hasn’t yet mentioned to her folks that Chris isn’t, and to the best of Chris’s knowledge, he’s the first black boyfriend the girl has ever had. Finally, as if all that weren’t enough, the Armitages are rich— Dad’s a neurosurgeon and Mom’s a psychiatrist— and the upstate New York neighborhood where they live is exactly the sort of place where you’d expect such people to settle. Still, Rose swears he’s got nothing to worry about. Her parents aren’t racists. They’re open-minded, they’re liberal, and her dad in particular is an outspoken Barack Obama fanboy. Taking Rose’s word for it and setting aside his last-minute jitters, Chris entrusts his dog and his apartment to his best friend, a TSA agent by the name of Rodney Williams (Lilrel Howery), and hits the road.

On the off chance that some of us in the audience are dense motherfuckers, something happens on the drive out to underscore the cause of Chris’s anxiety. It starts when a deer flings itself across the road from one expanse of woods to the other, and bounces hard off the right front corner of Rose’s Lincoln. That alone is unnerving enough, but the real trouble doesn’t arise until Rose calls 911 to report the incident. The state trooper who answers Rose’s summons (Brad Spiers) is patient enough in explaining that this is really a job for Animal Control, but then asks out of nowhere to see Chris’s license, even though it’s already been established that Rose was driving the car. Chris hasn’t got a driver’s license (plenty of city-dwellers don’t), and the cop turns combative when he hears that. Rose turns combative right back, objecting that the cop has no business asking her boyfriend for shit. Chris, meanwhile, starts imagining the forthcoming newspaper op-ed pieces defensively grousing that he was no angel. Luck is with him for once, however. You can practically see the gears grinding behind the trooper’s eyes as it dawns on him that he’s about to cross swords with a rich, white local who knows her rights. He grudgingly stands down, and the couple continue their journey angrier, but in peace.

Meeting the family proves as uncomfortable as Chris had feared, albeit in a stranger, subtler way. Dean (Bradley Whitford, from RoboCop 3 and The Cabin in the Woods) and Missy (Percy Jackson & the Olympians: The Lightning Thief’s Catherine Keener) Armitage are welcoming enough, but that’s frankly kind of the problem. Missy offers unsolicited hypnotherapy treatments to help Chris quit smoking. Dean keeps calling Chris “my man,” and goes on a bizarre tirade about his loathing of deer, as if to signal that he’s down with the urban lifestyle notwithstanding the home he’s made for his family out here in the sticks. He also makes a big production— a performance, even— of his positive attitude toward black people, showing off his souvenirs of a trip to Belize and telling Chris all about the time his father lost to Jesse Owens in the tryouts for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. And then there’s Rose’s little brother, Jeremy (Caleb Landry Jones, of Antiviral and The Last Exorcism). Jeremy is fucked up. A mixed martial arts aficionado, he keeps talking about how, with his “genetic makeup,” the proper training regimen could turn Chris into “a beast.” More obnoxious yet, before Missy puts a stop to it, Jeremy shows every sign of trying to talk Chris into letting him demonstrate his jujitsu headlock technique on him right there at the dinner table. (Wait— did he say headlock?) Rose is appalled and mortified. What really disturbs Chris, however, is the Armitage family’s two servants. They’re both black, for starters, which is rather off-putting under the circumstances. But they’re also as unpleasantly peculiar as Jeremy in their ways. Georgina the maid (Betty Gabriel, from The Purge: Election Year) could have come straight from Stepford, Connecticut, if only she were the right color. And Walter the groundskeeper (Marcus Henderson, of Pete’s Dragon and Django Unchained) is even screwier, somehow shy and friendly and threatening all at the same time. If Georgina acts like a robot, then Walter acts like a broken robot. Chris has no idea what the pair’s deal is, but he knows he doesn’t like it.

He likes what happens to him that night even less. Sometime after midnight, Chris gets up to sneak a smoke in the backyard (where he has his creepiest encounter with the servants yet), but gets caught coming back inside by Missy. She takes him aside into her study, where she proceeds to psychoanalyze him against his will, using a sort of stealth hypnosis to make him more tractable! Mrs. Armitage doesn’t seem to be just out to break him of his nicotine habit, either. Near as I can tell, she uses Chris’s lingering guilt over the death of his mother (which he believes he could have prevented) to create a psychic prison inside his subconscious mind. The Sunken Place, she calls it. So long as Chris’s consciousness is in the Sunken Place, he is unable to move, to speak, or to act in any way at all that could impact the world outside his skull. Missy releases Chris after just a few minutes, but if there’s an innocent explanation for her actions, I’m hard pressed to imagine what it could be.

Rose and Chris aren’t the only guests the Armitages are entertaining this weekend, as it happens. The timing of the couple’s visit coincides with that of a party Dean and Missy throw every year, which promises to assemble the densest concentration of clueless, rich, old white people that Chris will ever experience in his life. Unsurprisingly, it’s a trying day for him. The partygoers are mostly like Dean and Missy themselves, only more so. They all extravagantly act out their liberality toward, acceptance of, and admiration for black people, with results every bit as distasteful as outright bigotry, but much harder to rebuff or resist. The one exception is Jim Hudson (Stephen Root, from Red State and Night of the Scarecrow), the blind art dealer who turns out to have brokered quite a few sales of Chris’s photographs in recent years. So not only do the two men actually have something to talk about, but Jim can commiserate with Chris to some extent over his fellows’ unenlightened “enlightenment” and patronizing attempts at inclusiveness. Their conversation is the one really positive interaction that Chris has with somebody other than Rose all day.

Disturbingly, that remains true even when Chris spots one other black guy at the party, and hurries over to go talk to him. Dean and Missy’s Token Black Friend turns out to be just as bizarre as Georgina and Walter, and in much the same way. Furthermore, he’s at least dating, and may even be married to, Philomena King (Geraldine Singer, from The Town that Dreaded Sundown), a square-ass white lady more than twice his age, who barely lets him get a word in edgewise. And the most troubling part is, Chris could swear that he knows the guy from somewhere, even though the name Andrew Logan means nothing to him. Look closely, and you’ll recognize him too. That’s right— Andrew Logan is Andre Hayworth, the victim from the prologue scene, shorn of his goatee and dolled up in affluent honky suburbia’s idea of casual weekend attire. Chris surreptitiously snaps Logan’s picture on his cell phone, and appends it to a text message which he sends to Rodney back home, marveling over the escalating absurdity of the trip so far. (Rodney’s the one who connects Andrew with the widely publicized Andre Hayworth missing person case.) Then he and Rose sneak off to the lake to escape a round of bingo which Dean announces as the afternoon’s next amusement. The thing is, that bingo game looks a hell of a lot more like a silent auction to me, and there’s every indication that Chris is the lot being bidden on. And as if that weren’t creepy enough, Jim Hudson of all people is hell-bent on winning this thing…

A friend of mine who was born in Bristol, Virginia, spent most of his adult life in and around Washington DC, and retired to the South Carolina coast once said to me that the difference between Southern racism and Northern racism was that Southern racists hate black people in the abstract, but like the ones they know personally, while Northern racists like black people in the abstract, but can’t stand the ones they have to deal with face to face. Like all such sweeping pronouncements, it’s an exaggeration and a simplification, but it’s stuck with me for years because I think it captures something real and important. Get Out gets at the same thing. To hear the Armitage family and their circle tell it, they love black folks. But the truth is, their feelings are actually something closer to fetishism— and like my friend said, even that fetishism is largely abstract. In practice, when you get right down to it, the whole lot of them wish black people didn’t have to be so… well, black. Therein lies the despicable genius of the Armitages’ scheme. I don’t want to give the game away completely, but what Dean and Missy are running is basically the ultimate program of assimilationist integration, satisfying their fetish for an unreal, “ideal” blackness while negating the basis of their discomfort with the genuine article. And the way Jordan Peele presents it is discomfiting in the very best way. No white liberal with a trace of self-awareness will be able to watch Dean giving Chris the tour of the Armitage house and its grounds without thinking the whole time, “Oh Christ— am I that guy? Somebody please tell me I’m not that guy.” Then along comes the party sequence, and FUCKING HELL! I was about ready to crawl under my theater seat in vicarious embarrassment by the time the bingo auction got underway. Ironically, the revelation of what this party is really about comes as a relief. The Armitages and their guests being straight-up evil is somehow much easier to take than them merely being awful.

The challenge of a premise like this one is that it places hard limits on how scary the movie can be until the climax is ready to break out. Unsettling things can happen, but anything out-and-out frightening can befall only isolated, peripheral characters, lest it undermine the plausibility of the central figures sticking around. At the same time, though, it can be hard to hold a modern horror audience’s interest with the merely unsettling. The most successful approach to the problem is usually to invest heavily in developing a mystery with which to surround the disquieting events, so that the viewers can match their wits against the story instead of waiting passively around for the next murder or monster attack or spring-loaded cat. Look to The Wicker Man for a master class in that technique. Now Get Out is in no sense the equal of that movie, but Peele certainly has the right idea. We know from practically the start that there has to be a connection between the weird shit going on at the Armitage house and the abduction of Andre Hayworth, yet it’s by no means obvious what. Then there’s the parallel question of what in the hell actually happens to black people who fall into the clutches of Rose’s parents and their friends. And what about Rose herself? Are we really to believe that such a conspiracy could operate right under her nose without her so much as noticing anything odd? Granted, she acts innocent enough, but still…

At the same time, though, the scares in Get Out’s first two acts are a little scarier than normal for one of these “Welcome to Creepytown” sort of films. Whatever we may think of Walter and Georgina, that business with the Sunken Place is hardcore. Pretty much anybody would take that as their cue to leave. But Chris isn’t really a free agent in this, is he? If nothing else, he’s got Rose to think of, and he really doesn’t want to cause a fuss after her parents were so hospitable to him— nevermind that he’s kind of hated every second of their hospitality so far. Race is in back of it, naturally, but in a less obvious way this time. As always, the person with less power and status is the one who has to be accommodating, to give the benefits of doubts that would never be extended to him. For Chris, that means shrugging off even Missy’s hypno-intrusion as well-meaning— after all, he does wake up “cured” of any craving for nicotine the next day! It turns out that the conspiracy depends crucially upon that desire of its victims not to make waves, not to offend a gracious host, not to put unfair burdens on people caught in the middle. I suppose in theory a white boyfriend of Rose’s would feel himself under similar pressure, simply on account of Dean and Missy’s wealth and position, but similar isn’t the same. A white guy isn’t going to feel like he’s letting down all white guys everywhere if he fucks this up. He won’t have spent his whole life conditioned to let shit slide, no matter how offensive or degrading, in the interest of preserving his status as “one of the good ones.” Worrying about that kind of crap when people are trying to hypnotize you and turn you into God knows what? That’s how they get you.

The one really serious mistake that Peele commits in Get Out concerns the character of Rodney. He’d be more at home in a sketch on “Key & Peele;” here, he comes perilously close to the status of Odious Comic Relief. What stops him from actually crossing that line is that he’s usually legitimately funny. On the other hand, he tends to steal scenes in a bad way, making them about him when they more properly belong to Chris and his escalating unease. Especially toward the end, when Rodney assembles enough clues to develop his own worries about his friend’s safety, his comical antics undercut the masterful air of tension generated by the main plot. I’ll say this for Rodney, though: he comes through in the end, both for Chris and for the movie as a whole.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact