Effects (1979) ****

Effects (1979) ****

There was never any such thing as a snuff film— at least not in the sense that Raymond Gauer, national director for the Catholic-oriented anti-pornography pressure group, Citizens for Decency Under the Law, always used the term. Although I don’t doubt that the occasional psycho killer here or there might have shot home movies of his crimes for his own personal enjoyment, there is simply no evidence that a commercial trade in films depicting unsimulated murder, analogous to the trade in films depicting unsimulated sex, has ever existed, in any time or place. That so many people spent the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s believing in one nevertheless testifies to the efficacy of the Ninth Commandment of religious conservatism: Thou shalt bear false witness against thy neighbor whenever doing so is likely to enhance thy political power.

Gauer first mentioned snuff movies in January of 1974, in an address before the Los Angeles chapter of the Holy Name Society at said fraternity’s 38th annual breakfast event. The timing was significant, because the previous year had witnessed the bottoming out of a years-long downward trend in CDL’s* membership figures and number of active chapters, together with a concomitant decline in the organization’s reputation. Both problems had their roots in founder Charles Keating’s decision, in 1971, to transform CDL from a genuine grass-roots movement into a centralized, national-scale lobbying outfit with the help of direct-mail fundraising arch-grifter Richard A. Viguerie. Viguerie and his junk-mail empire increased CDL’s nominal income more than fourteen-fold, but since the lion’s share of that money disappeared into his own pocket, his involvement did the organization at least as much harm as good. Citizens for Decency Under the Law needed a new gimmick that would kindle fires in activist hearts instead of just generating more cash donations from change-scared old people, and Gauer found one by inventing a new low to which he could accuse his foes of sinking. Notably, at the Holy Name Society breakfast, Gauer limited himself to salacious supposition, positing pornographic movies that climaxed with the actual murder of their starlets as something that “may very well be filmed.” An article in CDL’s newsletter around the same time struck a comparably speculative tone, warning that “a progression to the ultimate obscenity” was “not hard to believe” given the porn industry’s easily observed habit of searching perpetually for new stimulations never wanked to before. But by the time Gauer debated David Friedman at a Writer’s Guild of America seminar that summer, he claimed not merely that snuff films might exist, but that he had in his possession evidence that they did. And according to the final CDL newsletter of the year, there were supposedly reliable reports of “as many as twenty-five ‘snuff’ films in current circulation.” Mind you, Gauer seemed to feel no obligation to turn any of this “evidence” over to the authorities, and when Friedman himself called an FBI agent of his acquaintance to ask if he’d heard anything on the subject, the agent replied that Gauer was a flake who was not to be trusted.

Alas, a great many other people did trust Gauer, and some of them did contact the FBI (and municipal police departments in every American city with a red-light district worthy of the name) with increasingly garbled versions of the rumors that he had started. Some of those, incidentally, looked a lot like repackagings of tall tales about the Manson Family that had circulated five years earlier. The story was picked up, too, by those unimpeachable paragons of journalistic integrity, the New York Post and the New York Daily News, which ran competing articles based on the same shoddy reporting almost simultaneously. Criminal investigations were launched all over the country in an effort to determine what, if any, truth lay behind the proliferating scuttlebutt (Hugh Hefner and Sammy Davis Jr. have snuff movies in their legendary porn collections! Dennis Hopper saw one while he was down in Durango making Kid Blue! The New York blue-movie trade papers openly advertise for actresses willing to be killed on film!), but not a one of them yielded anything more than yet more rumors. Even the FBI’s Cincinnati field office— in the same city as CDL headquarters— initially got only a vaguely worded promise that some Citizen for Decency would get back to them eventually with whatever Gauer had… which turned out to be nothing more than that same old story about the Manson Family filming Satanic rituals of human sacrifice, with the names conveniently left out.

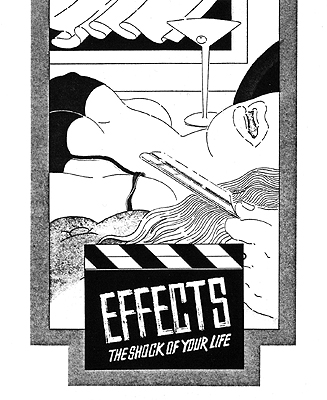

But as we’ve discussed before, there are few mental exercises more productive for tellers of horror stories than to ask oneself what it would mean if mendacious conservative busybodies were right about whatever has them lathered up this week. The latter half of the 70’s thus saw a surprising variety of entertainment media responding in one way or another to the snuff film controversy. Snuff movies and the makers thereof turned up as plot points not merely in the likes of Last House on Dead End Street or Greta the Mad Butcher, but even in such unlikely places as Emanuelle in America and the broadcast TV cop dramas, “Police Story” and “The Rookies.” A new wave of Mondo movies emerged, purporting to compile documentary footage of actual human deaths, including historical atrocities, judicial executions, fatal accidents, and so forth. Ruggero Deodato turned around and riffed on those to scarifying effect in Cannibal Holocaust. Allan Shackleton, in a perversely brilliant display of cynicism, added a crudely shot coda to Slaughter, a five-year-old Manson-panic exploiter from Michael and Roberta Findlay so drearily lousy that nobody wanted it even on 42nd Street, and released it under the title Snuff with a promotional campaign designed to snooker audiences into thinking that it was the movie everybody was talking about. From what I’ve seen, though, the most thoughtful and engaging product of late-70’s snuff-mania is Effects, an unjustly forgotten film originating within the Pittsburgh-based indie horror scene that sprang up in response to George Romero’s early hits. Effects got buried upon its initial appearance by a bad distribution deal with a company that almost immediately went out of business, and fared little or no better in the VHS and DVD eras. It’s back in circulation now, though, in a Blu-Ray release curated by the American Genre Film Archive. Maybe this time, Effects will become at last the cult classic that it always deserved to be.

Independent producer-director Lacey Bickel (John Harrison, from Knight Riders and Jack’s Back, who also composed and performed this picture’s score) is making a movie. It’s a possession story of sorts, in which a businessman and his wife fall prey to a supernatural entity of uncertain nature and origin that has apparently taken up residence in the woods surrounding their home. Whatever’s out there, it fills the couple’s heads with hallucinations and intrusive thoughts of violence, until finally they need just the slightest push to murder each other. The title is pretty great, too— the kind of oblique but evocative thing that works like catnip on me even before you factor in my inexplicable love for titles that are also complete sentences. It’s called Something’s Wrong. Playing the protagonists are real-life spouses Barney (Bernard McKenna) and Rita (Debra Gordon, of Bloodsucking Pharaohs in Pittsburgh and Sorority Row), while a lout by the name of Nicky (Tom Savini, from Martin and Beyond the Wall of Sleep) assays the role of a third character whose function is unclear beyond that he figures prominently in the wife’s hallucinations. The crew is comparably miniscule: cinematographer and special effects artist Dominic (Joseph Pilato, from Day of the Dead and Empire of the Dark), gaffer Celeste (Susan Chapek), and a guy called Lobo (Chuck Hoyes, of Haunted Maze and Home Sweet Home) who might best be thought of as the location-shoot equivalent to a gigging rock band’s roadie.

Among those people, only Nicky and Barney seem to like Lacey very much, although everyone but Celeste (who just plain can’t stand the guy) displays considerable respect for him and his achievements in the realm of regional guerilla cinema. Nor is Lacey’s admittedly unappealing personality the only source of friction on the set. Barney and Rita’s marriage looks like it’s teetering toward complete implosion. Dominic has clearly fallen for Celeste, and although she has feelings for him, too, they’re unmistakably not on anything like the same level. Everyone rightly thinks Nicky is an asshole. And it’s taking a toll on the lot of them to be living together in the same woodland lodge that serves as the principal shooting location, with no real privacy or personal space. Also, the whole operation runs on booze and cocaine, which is rarely conducive to tranquil cooperation. Still, the vibe overall is one of embattled professionalism, with everybody giving whatever they’ve got to the project, no questions asked.

It’s plain from jump, however, that something’s wrong on the set of Something’s Wrong. There are video cameras concealed all over the lodge, which only Lacey and maybe Celeste seem to know about. Nicky evidently has a second, off-the-books role in the production, which he discusses only with the director himself. The basement of the lodge contains a secret space outfitted like a television studio control room, where Lacey leads an entire second crew processing the signals from the hidden cameras. The regular crew audition a girl (Cindy Sebastian) whom Nicky brings by the lodge, but Dominic and Celeste are never called upon to film whatever scene she was under consideration to perform. And perhaps most ominously of all, Lacey is occasionally seen working with a script entitled not Something’s Wrong, but Duped: The Snuff Movie.

The picture toward which all of those signs are pointing comes into focus one night about two thirds of the way through the shoot, when Lacey, Dominic, Barney, and Lobo finish watching the day’s rushes down in the readily accessible part of the basement, and get to talking over beer and blow about the current state of the art and business of horror filmmaking. Director and cameraman get into a debate over the relative importance of shock and suspense, with Dominic, despite doubling as Something Wrong’s goremeister, taking a hard line in favor of leaving things to the imagination. At that, Lacey retrieves a reel of 16mm film from the adjoining room, suggesting as he does so that the contents of the reel might change his companion’s mind. Then he fires up the projector, and watches Dominic and Lobo (Barney has obviously seen the film already) while they watch the screen. What it shows (in silent, grainy monochrome, hinting that the film was blown up from an 8mm source print) is a cramped and somewhat squalid room in which a masked man ties a seminude girl (Jackie Lahanne— later a costumer for “Solid Gold!”) to a chair, and proceeds to grope her roughly. Then he begins to caress her menacingly with the flat of a Bowie knife, cutting off bits of her underwear in between strokes. Finally, he takes to slashing the girl over and over, practically bathing in the blood that sprays from her wounds. Lacey’s comments about the film’s provenance afterward are both evasive and self-contradictory. What if he told Dominic and Lobo that he got the reel from a collector overseas? What if he told them instead that he made it himself years ago, during his film school days? What if he said the girl was one of his classmates, and that the film was an exercise in employing the new special effects techniques that were emerging in the early 1970’s? Or what if he said it was an authentic record of her actual murder? Whatever the truth, both men are spun, but they eventually come down in very different places. Dominic is sickened by the entire affair, and stomps sullenly off to bed. Lobo is aroused on some level even more primal than sex, and probably couldn’t tell you himself whether it would be more exciting if Lacey’s enigmatic film were real or fake.

The sharp-eyed will have noticed something that might be taken to resolve the question, however. That Bowie knife the killer was using in Lacey’s is-it-or-isn’t-it snuff reel? It belongs to Nicky, the very same team-member who recruited that dancer for the mysterious audition the other night. You know— the girl whom nobody ever saw again? The screening in the basement was also an audition of sorts, which Lobo passed and Dominic failed. Lobo, therefore, will be let into the director’s confidence, joining Nicky and a hitherto unseen man called Scratch (Blay Bahnson) the following morning on a hunt in the woods with Dominic as the prey instead of vice versa. Remember, though, that the new snuff movie hiding beneath the production of Something’s Wrong is apparently entitled Duped. It turns out that title is even more apt than we’ve already been given to understand.

That’s my favorite aspect of Effects. Lacey is running what amounts to about eight concurrent life-or-death versions of the Nigerian Prince e-mail scam, with the victims suckered in via an invitation to take part in a criminal conspiracy. Nearly all of Bickel’s accomplices are also marks, and nearly all of his marks are also accomplices. Writer/director Dusty Nelson leaves the audience with a lot of work to do in sorting out exactly who is in on exactly which parts of Lacey’s scheme, and from exactly which points in the story. He plays completely fair in doing so, however, so that the task of assembling all the pieces is not merely rewarding, but downright compelling. When I saw Effects at the Riverside Drive-In outside of Pittsburgh this past April, it was the last of four movies in a single night, and the show didn’t let out until well after 3:00 in the morning. Nevertheless, the group of friends with whom I attended had been so energized that we spent the whole 45-minute drive back to the hotel in animated discussion over the characters’ varying degrees of awareness and culpability.

Nor does Effects rely solely Nelson’s caginess about how all the interlocking double-, triple-, and quadruple-crosses fit together to keep you pleasantly off balance. Remember that this is a horror movie about people making a horror movie, and that in contrast to most other such films I’ve seen, its story is configured so that the movie-within-the-movie can plausibly remain under production right up until the start of the endgame. Furthermore, although the ostensible premise of Something’s Wrong is very different from that of Duped (or by extension, that of Effects itself), the three plots mirror and echo each other constantly. We frequently can’t be sure until the end of any given scene whether we’re watching part of Something’s Wrong, part of Duped, or strictly part of Effects. This is one of those rare horror films that make it fun to be confused.

But returning now to the snuff controversy, Effects tackles the subject from an angle that I don’t think I’ve ever seen used before, even though that angle eventually became central to the entire affair. It starts by asking how anyone could be sure they’d recognize a snuff film in the event that they actually saw one. After all, the average person has never seen murder or dismemberment, and therefore has no real-world baseline against which to evaluate an image of either as captured by a motion picture or video camera. Meanwhile, by the turn of the 80’s, graphic simulations of carnage had become commonplace in horror cinema, and artists like Tom Savini had grown so adept at faking the destruction of the human body that audiences were essentially left to take it on faith that what they were seeing wasn’t real. Factor in movies like Snuff, Faces of Death, and Cannibal Holocaust, which deliberately sought to confuse the issue in various ways, and the thought experiment embodied by Lacey Bickel takes on real salience. Without giving Raymond Gauer’s scaremongering any more credence than it deserves, could the market conditions and technology of the late 1970’s have enabled a real snuff film to hide in plain sight, precisely by posing as a fake one? Effects inverts the moral calculus of the snuff film legend, and in doing so makes it more plausible than the standard narrative had ever been. In this scenario, what Bickel exploits is not his market’s addictive desire for ever-stronger stimulation, heedless of the cost at which each new rush is obtained, but rather the jaded indifference of an audience that has been trained never to believe its eyes.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact