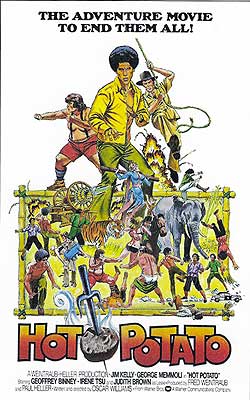

Hot Potato (1975/1976) -*

Hot Potato (1975/1976) -*

Remember the platitude with which Blade Runner’s Eldon Tyrell tried to fob off the Replicants when they came to him for an extension to their four-year lifespans? “The light that burns twice as bright burns half as long,” he said, “and you have burned so very, very brightly, Roy.” The blaxploitation craze of the early 70’s burned brightly, too, and in point of fact, it lasted just a little longer than one of Blade Runner’s androids. So it’s understandable, to some extent, why Warner Brothers would want to shift gears with their sequel to Black Belt Jones. Also understandable (again, to some extent) was the specific new direction they chose for Hot Potato. If you think back, Black Belt Jones portrayed its title character as some sort of freelance government agent, a bit like a karate-fighting, one-man Impossible Missions Force. If blaxploitation was passé, then why not show the kind of work Jones normally did, when the particulars of his mission didn’t call him home to battle mobsters looking to seize control of his old neighborhood? Considerably less understandable, however, was the decision to make Hot Potato also a stupid comedy. And not understandable at all is how Hot Potato’s karate sequences could fall so far short of its predecessor’s already abysmal standard that they could justly be used to establish an Absolute Zero baseline for cinematic martial arts. Only a bit of charming loopiness in what passes for the plot, plus an extremely occasional successful gag, saves this movie from establishing Absolute Zero more generally as well.

The imaginary nation of Chang Lon, located on or near the Malay Peninsula, is on the brink of civil war between its communist and Western-aligned political factions. Worse yet, tribal warlord and would-be supervillain Carter Rangoon (Sam Hiona, from Warlords and Friend of the Family II) is plotting to exploit the burgeoning conflict by promising his allegiance to both sides. Presumably Rangoon envisions himself as the last power-player left standing after the major combatants have exhausted themselves. Of course, any such plan presupposes that civil war actually break out, and recent developments abroad have suddenly called that prospect into question. If a package of foreign aid currently under debate in the United States Senate passes, it could sufficiently improve the lot of Chang Lon’s poor to make them lose their taste for revolution— and then where would Rangoon be? Obviously, he needs some way tilt the scales of American politics toward isolationist stinginess, and with that in mind, he’s had his men kidnap June Dunbar (Judith Brown, of Willie Dynamite and Women in Cages), daughter of the Senator Dunbar who has thus far been the aid bill’s most influential proponent. Rangoon will feed her to his pet tigers unless the senator reverses his position.

Senator Dunbar does not roll over that easily, however. No sooner does he get the proof-of-life call from his daughter announcing her kidnapper’s demands than he turns around and phones a general of his acquaintance (Ron Prince, from Amazons and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song) to demand a military intervention on June’s behalf. That isn’t going to fly (“We’re not welcome there, sir”), but there might be a plausibly deniable alternative. The US happens to have a pair of operatives in the vicinity right now, although they don’t belong to any officially constituted agency. Just the sort of people you want, in other words, when you can’t afford to be seen doing something. If anybody can slip into Chang Lon, free June Dunbar, and slip back out again without raising a fuss, it’s Black Belt Jones (Jim Kelly, reprising his old role) and Johnny Chicago (Raw Force’s Geoffrey Binney)!

If you remember the preceding film, then you already know what a retrograde macho-man Black Belt Jones is, and Johnny Chicago is considerably worse. So it’s basically inevitable that their liaison to the Chang Lon authorities turns out to be a woman— Detective Sergeant Pam Varaje (Irene Tsu, from The Sword of Ali Baba and Island of the Lost)— and that neither Jones nor Chicago will take her seriously until they’ve seen her beat the asses of about a dozen of Rangoon’s goons (his RanGoons?) with only minimal assistance from them. And I suppose it’s inevitable, too, that Hot Potato will insist from then on upon pretending that some kind of sexual tension exists between her and Jones. Lots of luck finding an audience credulous enough to buy that, though. In any case, Jones wants further backup on the mission, even after Varaje establishes her martial arts credentials, and the trio stop in at the Blue Moon— the rowdiest whorehouse in the capital, and a favorite haunt of Leonardo “the White Rhino” Pizzarelli (George Memmoli, from The Phantom of the Paradise and Americathon). They catch Pizzarelli in the endgame of an eating contest against the hefty madam of the establishment, with $700 or a session with three of the Blue Moon’s most talented prostitutes on the line. Somewhat surprisingly, Jones, Chicago, and Varaje are considerate enough to wait until Pizzarelli has finished enjoying his winnings before dragging him off to the jungle compound where Rangoon is believed to be holding June.

At first, the rescue mission looks like a resounding and uncomplicated success. The fortifications around Rangoon’s base were not built to withstand attack by either elephants (which the agents rent from some neighboring farmers) or White Rhinos, and the villain’s extremely accommodating soldiers politely wait their turns to be pummeled individually, even when they have one of their enemies surrounded at odds of eight or ten to one. The lock on June’s cell is flimsy, and the men standing guard over her are easily overcome. Carter Rangoon himself is nowhere on the premises, nor is there any sign of his top lieutenants, the native Pujo (Somcjai Meekunsut) or the Western soldier of fortune Krugman (Hardy Stockmann). The RanGoons don’t even seem to be giving chase as the agents withdraw with the liberated hostage toward the river and their waiting getaway boat. Suspiciously easy, all in all, and you won’t be surprised to learn that Rangoon is up to something. The woman whom Jones and company “freed” was not June Dunbar at all, but a lookalike by the name of Leslie Miles. Leslie works for Rangoon, although I’m at a loss to understand her actual mission on his behalf. The villain says that this switcheroo will buy him and his forces the time they need, but it seems like there’d have to be at least twenty simpler and more effective ways to do that.

It doesn’t really matter what Rangoon wants Miles to do for him, though, because she’s double-crossing him for reasons not much less obscure. Before Leslie departed Rangoon’s palace to take up her decoy position at the jungle fortress, she stole the two identical letters of allegiance which the would-be dictator was fixing to send the leaders of each side in his longed-for civil war. It would be very inconvenient for Rangoon if his planned duplicity were exposed, and the moment he discovers what Leslie has done, he shifts gears to put as much effort into recapturing her as he would into retrieving the real June Dunbar. He dispatches Krugman into the jungle at the head of an army of mime-ninjas, while simultaneously sending Pujo to call in an early favor from the chief (Lam Ching-Ying, from Encounter of the Spooky Kind and Mr. Vampire) of one of the tribes that had already agreed to back his projected coup. Don’t you go thinking, though, that Rangoon’s newfound sense of urgency is in danger of spreading to the filmmakers themselves…

“Okay,” I hear you starting to protest, “but what do potatoes— hot, cold, or room-temperature— have to do with anything?” Ah. Well. You see, when the general takes Senator Dunbar’s phone call demanding military action to rescue his daughter, and finds himself having to parry the senator’s barely-audible harangue like the world’s worst Bob Newhart impersonator, he concludes his explanation of why the army’s hands are tied by mumbling sheepishly, “Yessir. It’s a hot potato, sir.” It’s easy to miss, and the situation in Chang Lon will never be described that way again, but that isn’t the real problem with calling this movie Hot Potato. As a friend of a friend astutely observed online a while ago, “potato” is the kind of word that should be kept as far away as possible from the title of any action/adventure film. I hear Hot Potato, and I immediately imagine a Crown International Pictures sex comedy about college girls raising the money to fix up their recently condemned sorority house by starting LA’s first topless food truck business. And you know what? I guarantee you that notional Crown International Hot Potato would have been better than the movie that actually bears the name.

Most bad comedies are bad at being comedies. Hot Potato does have that fault, but it’s even worse at being an action picture. A truly incredible amount of nothing happens over the course of this movie, as it wastes its time and ours on boat rides, tribal weddings, religious processions, and ostensibly romantic interludes between characters who have about as much chemistry together as gold and neon. When we should be worrying about Krugman and/or Pujo closing in on Jones and company, we get instead an entire pointless subplot about Pizzarelli accidentally winning a wife (Metta Roongrat, from Ghost of Guts-Eater and Ghost Hotel) and child (Supakorn Songermvorakul) in a wrestling match. And even when action does break out, it’s invariably bad and boring, sometimes lacking any discernable motivation at all. Take, for instance, the time when Jones gets up in the middle of the night, wanders away from the party’s campsite, and becomes embroiled in battle against a squad of parang-wielding statue-impersonators outside some ancient temple. Who the fuck even are these guys?!?! Why are they lying in ambush here, of all places?! How does Jones fail to notice them standing around, looking very much not like statues, until he’s trading blows with them?

The fools I really pity, though, are the ones attempting to watch Hot Potato as a karate movie specifically. It’s difficult to describe how thoroughly this film goes wrong in that mode, but those in the know might get the picture if I say that director Oscar Williams makes Robert Clouse (who directed Black Belt Jones and Gymkata, along with a couple genuinely good martial arts movies) look like Lau Kar-Leung. Jim Kelly, meanwhile, reveals himself as possibly the worst fight choreographer ever to cash a check for that service from a major film studio. At a minimum, a decent chopsocky set-piece must accomplish two things. It needs to show off the combatants’ moves to good effect, but it also needs to prevent the audience from thinking about what those other five guys are doing while these two are fighting each other. Hot Potato’s fights fail on the first count because few of the castmembers save Kelly himself had any moves to show off, and they fail on the second count because one can always see for oneself what the other five guys are up to: they’re standing in the background, in half-assed approximations of the horse position, awaiting their turns to get taken out. Kelly spends most of his fighting time standing around, too, either trying to convince us that he’s tensing to meet multi-directional attacks that never come, or holding his current opponent in an interminable arm-lock while his fellows take no advantage of their target’s preoccupation. It also seems telling that Jones never fights either Krugman or the chieftain called to the villains’ aid by Pujo. Hardy Stockmann and Lam Ching-Ying both had martial arts training (tae kwon do for Stockman, and all the thousand things one might pick up as a longtime Shaw Brothers stuntman for Lam), and could certainly have held up their ends of a duel with Kelly. But to all appearances, the last thing Kelly wanted was a fight that Black Belt Jones had to work to win. Even the climactic showdown against Carter Rangoon goes mostly Jones’s way throughout. An obviously invincible hero is a boring hero. Even when “the good guys win in the end” is a basic genre assumption, it has to look in the moment like there’s some chance they might not, or at least like their victory is costing them something. There’s nothing impressive or exciting about watching Kelly knock down 50 dudes half his size, none of whom ever manage to lay a finger on him.

The last thing I want to talk about with regard to Hot Potato is not so much a criticism as a mystery. When Leonardo Pizzarelli first appeared onscreen, clad in a toga for no discernable reason, and crowned with a laurel wreath, I was pretty sure I had the White Rhino’s number. He was Secret Agent Bluto Blutarski. And indeed George Memmoli plays Pizzarelli as a Belushian chaos clown, doing everything as loudly, obnoxiously, and destructively as possible. But then I remembered something— Animal House wasn’t released until 1978! The White Rhino can’t be a Blutarski knockoff, because there wasn’t any Blutarski to knock off yet! So was Bluto derived from some earlier Belushi character— maybe someone he’d played on “Saturday Night Live”— and that guy was the basis for Pizzarelli as well? Or were Memmoli and Belushi alike riffing on some older archetype that I’m not aware of, due to my low tolerance for pre-1970’s comic sensibilities? It won’t make Pizzarelli any easier to get along with one way or the other, but the puzzle does make him a slightly more interesting figure.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact