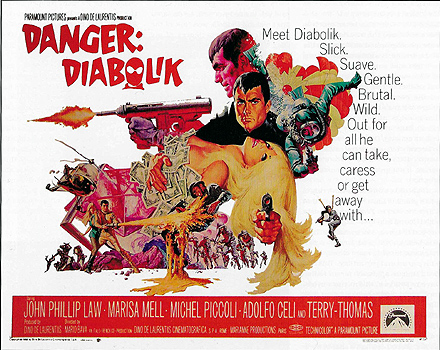

Danger: Diabolik / Diabolik (1967/1968) **Ĺ

Danger: Diabolik / Diabolik (1967/1968) **Ĺ

Itís possible that Dino De Laurentiis was the first movie producer I ever knew by name. Iím not sure about tható it could also have been George Lucasóbut I do know for certain that I was acquainted with De Laurentiis when my age was in the single digits. The reason why is simple enough: he was the jackanapes who fucked up King Kong. That remains the first thing I think of whenever I hear the name Dino De Laurentiis even now, but that isnít entirely fair. The man was in business for a long, long time, and although he was responsible for more than his and any other four producersí share of utter stinkers, he also made some great stuff, some interesting stuff, some memorable and challenging and adventurously weird stuff. Truth be told, some of the stinkers fall into the latter categories, too. In the final assessment, De Laurentiis accomplished something that nobody else ever did, for better or for worse. He brought a distinctly Italian filmmaking sensibility to Hollywood, combining a willingness to try anything to get a rise out of people, however illogical, distasteful, or absurd, with a knack for marshalling immense resources and an unfailing instinct for the crassest possible commercialism. De Laurentiis didnít set up shop in the US until the 70ís, however. He had an entire career before that, and it wouldnít do for me to let that other career go completely unremarked in a B-Masters roundtable dedicated to the man and his works.

Among the most conspicuous patterns in Dinoís Hollywood period is his tendency to latch onto a theme and then harp on it obsessively until heíd worked it out of his system. Well, it turns out that a bit of that behavior was already in evidence back in Europe. Consider, for example, Barbarella, the international hit that convinced De Laurentiis that Italy wasnít big enough for him anymore. Although it remains probably his most famous attempt to make a flashy, sexy, outrageous cinema spectacle from comic book source material, Barbarella was by no means the only such production to bear Dinoís imprint. Indeed, another one preceded it into release by some months. While Barbarella was temporarily mired in preproduction difficulties, De Laurentiis turned his attention to adapting one of Europeís first adult-oriented comics, Diabolik.

Originally the creation of Milanese sisters Angela and Lucianna Giussani, Diabolik was an antihero comic inspired by the Fantomas novels of Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvetre. The series was as successful in Italy as the likes of Superman and Batman have ever been in the United States, and gave rise to a whole ecosystem of imitators. One of the latter, the skeleton-suited Kriminal, had made the jump from print to film in 1966, so it was only natural that someone like De Laurentiisó that is, someone who knew how to raise enough money to afford the kind of licensing fee which the Giussani sisters and their publishers were in a position to commandó would take a stab at adapting the original. Dino also saw a possibility that the makers of Kriminal had missed. Even if audiences overseas had never heard of Diabolik by name, wasnít a film about a gadget-happy superthief ideally positioned to exploit the international popularity of both Bondian fantasy espionage and Oceanic heist capers? Well, not really, as it turned outó but the point is that De Laurentiis was able to convince no less a distributor than Paramount to give it a try. And although the desired mass Anglo-American audience eluded Danger: Diabolik, the film did garner a cult following, especially among people who never outgrew their taste for comics. In those circles, Danger: Diabolik would enjoy for decades a reputation as probably the only comic book movie to successfully capture the essence of the source medium.

In some non-specifically Western European capital, the Ministry of Finance is putting itself and the national police to what seems like an awful lot of trouble to safeguard the transport of $10 million from one vault facility to another. The massive police motorcade will actually escort a dummy shipment of blank linen-paper slips while the money goes incognito in a Rolls Royce limousine manned by cops disguised as dandyish high government officials. Granted there was a lot of lawlessness, terrorism, and organized crime in Europe in those days, but isnít that a bit much? Not according to Inspector Ginko (Michel Pieroli, from Amazons of Rome and Leonor: Mistress of the Devil). Indeed, Ginko fears that even these extravagant precautions will not be enough to thwart the one criminal heís really worried aboutó the seemingly unstoppable arch-thief known only as Diabolik (John Phillip Law, of Alienator and The Spiral Staircase). Ginko is right to be concerned. When Diabolikís signature black Jaguar E-Type (he maintains a whole fleet of the things) arrives on the scene, itís stalking the limo instead of the armored truck with the fake cash. Diabolik reaches the dock before the money does, in plenty of time to set a trap for the police. He makes a clean getaway, too, thanks to an assist from his girlfriend, Eva Kant (Marisa Mell, from The Secret of the Red Orchid and Diary of an Erotic Murderess). Then the pair return to their secret underground lair to Scrooge McFuck atop and within their monstrous new pile of cash.

Soon thereafter, the Minister of the Interior (Terry Thomas, from The Abominable Dr. Phibes and The Vault of Horror) holds a press conference at which he announces that the government has voted to reinstate capital punishment. Thatís sure to deter the criminal element, right? Perhaps, but it definitely does not deter Diabolik and Eva from crashing the conference disguised as journalists, or from flooding the room with concentrated laughing gas. The criminals slip away while the minister, the press, and the police all double over in hysterics on national television, as if in comment on the governmentís plans.

So great is the official embarrassment that the Chief of Police (Claudio Gora, of Seven Bloodstained Orchids and An Angel for Satan) is able to get Ginko and his unit invested with emergency powers. (The Minister of the Interior, meanwhile, resigns in disgrace and takes up a new position as Minister of Finance. Iím sure thatís supposed to be a joke, but I canít make out more than its outermost contours.) Strangely, though, it isnít Diabolik who feels the squeeze of Ginkoís new authority, but an ordinary mob boss called Valmont (Adolfo Celi, from Fragment of Fear and Holocaust 2000). The inspector knows what heís doing, however. He hopes that by making life difficult for Valmont, he can force the gangster and his minions into an alliance against Diabolik. Meanwhile, Ginko sets a trap of his own by encouraging the press to publicize the priceless emerald necklace that Lady Clark (Catherine Bocatto, from Phantom of Death and The House by the Lake) will be wearing when she accompanies her husband, Sir Harold Clark (Edward Febo Kelling), on an official state visit in a few days.

You probably donít need me to tell you that Diabolik proves too slippery for Ginko once again, absconding with the jewels despite a host of inventive security measures. Valmont, however, has a tad more luck. It was Eva who cased the castle where the Clarks were staying, a mission which she carried out in the guise of a prostitute. One of the real hookers on that block (Lucia Modugno, from Isabella, Duchess of the Devils and The Evil Eye) was an employee of Valmontís mob, and she figured out quickly enough that Eva was no streetwalker. When the whore reports what she saw, Valmont calls a certain Dr. Vernier (Giulio Domini, from The Lady of Monza and Death Laid an Egg), whose practice is built on ministering to those who would rather not explain how they got their injuries. Vernier claims not to recognize the identikit sketch of Eva made from the hookerís description, but Valmont knows at once that heís lying. His men abduct Eva from Vernierís clinic when she goes to see the doctor about a shoulder she sprained during a getaway, then lets it be known through underworld channels that the price for the girlís return is both Lady Clarkís necklace and the $10 million that Diabolik heisted at the start of the film. Of course, at the handover point, Valmont is expecting to hand Diabolik over to Ginko. The arch-criminal squirms his way out of this one, too, but he has to fake his death in order to do it, relying on Eva to spring him from the morgue before he gets autopsied. Valmontís death, on the other hand, is the real thing.

Next, the new Minister of the Interior (Renzo Palmer, from Spirits of the Dead and The Eroticist) latches onto a plan so obvious that you have to wonder why it wasnít tried before; he offers a million-dollar reward for Diabolikís capture. It turns out thatís not nearly the slam-dunk the minister imagines it to be, however. When Diabolik learns of the reward, he sends a letter to the Ministry of the Interior scolding that if the government intends to misuse the publicís money like that, then heíll have to take steps to deprive them of it. The next thing you know, bombs are going off at all the government buildings that have anything to do with the collection or management of taxes. The Minister of Financeó which is to say the disgraced ex-Minister of the Interioró is forced to make a fool of himself on television again, this time by begging the citizenry to pay whatever they believe they owe in taxes this year (since all the countryís tax records have gone up in smoke). Inevitably his pleas fall on deaf ears, and now the authorities are in a real pickle. With no tax money coming in, the only way for the government to meet its operating expenses is to sell off the nationís gold reserves. Thatís bad enough, but worse yet is that a gold shipment of that magnitude is sure to be an irresistible target for Diabolik. Someone has the bright idea to melt all the gold into a single 20-ton ingot, and to seal that inside an impenetrable steel pod. Not even Diabolik could pilfer something that unwieldy, right? Ginko isnít so sure. Indeed, the way he sees it, stealing the unstealable is basically Diabolikís whole shtick. The inspector and his men had better be ready for anything when the train carrying the gold leaves the station.

Practically every culture at least occasionally makes heroes out of its outlaws, but you donít have to look too closely to see that something out of the ordinary was happening in Italy during the 1960ís. That stunt with the tax offices notwithstanding, Diabolik doesnít make a very convincing Robin Hood. His crimes are motivated not by any notion of economic justice or retribution against evildoers more predatory than himself. He isnít even in it for personal advancement in the ordinary sense, although surely it must cost a bundle to maintain a lifestyle like his. No, Diabolik does what he does entirely because crime makes Eva soak through her panties, and the bigger and more outrageous the crime, the better she likes it. And the thing is, Diabolik is easily the nicest of 1960ís Italyís comic book supercriminals! Kriminal is much worse than Diabolik; Satanik is much worse than Kriminal; and Killingó my God, Killing might even be worse than Fantomas! Yet in every case, itís the villainó the robber, the murderer, the terroristó that captured the publicís adoration, rather than the indefatigable police inspector futilely pursuing him (or her, in Satanikís case) through installment after installment. The only way I can think of to explain it is to point to the governments that Italy had for most of the 20th century. Since the rise of Mussolini in 1922, Italy had known little but tyranny, incompetence, and corruption, and frequently had to contend with two or more of those things at once. I dare say that 40 nigh-continuous years of multivariate misrule would leave most peoples in the mood to fantasize about watching the world burn.

Some support for that fantasy catharsis theory may be gleaned from Danger: Diabolikís oddly lighthearted tone. It isnít just that Diabolik has the filmís clear sympathies. Itís that Inspector Ginko is totally alone on his side of the law in not being a ridiculous fool. And the higher an authorityís rank, the bigger a boob he is, until the man at the top is a graduate of the Carry On movies, playing the Lord Twittingford (of the Bollockshire Twittingfords) type as only British comic actors can. It would take a humorless viewer indeed to deny that plunging the unnamed nation of Danger: Diabolik into anarchy and chaos is all in good fun.

Unfortunately, presumed antipathy toward bumbling authority figures is about the only reason that Danger: Diabolik offers for getting invested in its story. Diabolik himself is a complete cipher, with no recognizable personality outside of his obvious affection for Eva. Eva is at least slightly more developed, insofar as we can see that sheís insatiably greedy for other peopleís stuff, and that she subscribes to something resembling Donald and Donna Dasherís ďcrime is beautyĒ philosophy. Ginkoís sole human trait is his devotion to law and order in a movie that celebrates the opposite, and he carries the further unenviable burden of being a guy with no sense of humor whatsoever in what is basically a comedy. Not that the characters in Louis Feuilladeís Fantomas series had much more depth or solidity, but the stark delineation of Fantomasís evil in those films clearly established what was at stake and why we should care. Treating Diabolik and his foes alike as figures of fun creates a hollow space at the center of Danger: Diabolik which leaves it weightless and ultimately unsatisfying.

On the other hand, Danger: Diabolik has Mario Bava in the directorís chair, and thatís almost always worth something. Expect plenty of Bavaís usual cunning glass matte paintings, lovingly crafted miniatures, and eye-catching camerawork, although this movie is surprisingly short on vividly colored lighting. More importantly, though, Bava achieved something here that would elude the makers of virtually all other comic book movies until the 21st century. He successfully captured the visual dynamism of comics, and translated it into moving pictures. I know that doesnít sound like something worth getting excited about, but look closely. All too often, filmmakers who take on comics adaptations without previous experience with the medium (whether as creators or as fans) get hung up on the idea of static tableaux, and imagine that a proper comic book movie should sort itself into a series of such images. Bava, however, understood that a reader of comics doesnít mentally experience them that way at all. Rather, each panel depicts a frozen instant of action, cuing the readerís mind to fill in all the hectic motion surrounding it in time. So instead of engineering excuses for dramatic posing and the like, Bava fills Danger: Diabolik with fast pans, whiplash-inducing zooms, and other jarring yet precisely controlled camera movements. He also makes constant subliminal use of windows, mirrors, slatted bedsteads, knickknack shelves, and so forth to create the suggestion of panel shapes within the frame. I suspect that Bavaís background as a painter was a major factor here. Even if he mostly limited himself to landscapes, still lives, and figure studies in practice, he would certainly have learned how to see the implicit movement hidden in a well drawn or painted action scene, and to recognize that that implication was at least as important as anything actually present on the paper or canvas.

Bava found it a trying experience to work with Dino De Laurentiis. The producer liked to think big, and he was ramping up toward the phase of his career in which thinking big would give way to out-and-out megalomania. Although it was chump change by Hollywood standards, Danger: Diabolikís $3 million budget was the largest that Bava had ever enjoyed. Mind you, he didnít enjoy it very much. Indeed, his experience of Danger: Diabolik was that De Laurentiis was constantly pushing him to waste money. The producer wanted him to build things that he felt would be better handled with miniatures and matte paintings, and to tolerate the time-sucking star behavior of Catherine Deneuve (who had been Dinoís choice to play Eva). De Laurentiis was also terrified of censorship entanglements (Italy was undergoing a period of backlash against crime and horror comics similar to that which had transformed the American comics industry in the 1950ís), and nagged Bava constantly to keep the violence bloodless and unthreatening. Bava won most of those arguments in the end, and so effective was the directorís fanatical frugality that he handed in a film that looked conspicuously better and more lavish than Barbarella (shot concurrently on triple the budget of Danger: Diabolik) while spending less than one sixth of the money that De Laurentiis had allocated. Thrilled and astonished, De Laurentiis invited Bava to make a sequel with the 2.6 million unspent dollars, but Bava wasnít having it. Indeed, he still wasnít having it eight years or so later, when Dino tried to convince him to tackle the special effects on King Kong. (Howís that for a ďwhat might have been,Ē eh?) I canít say I blame Bava, nor do I see much point in trying to continue this story beyond where it leaves off. As parting shots go, the conclusion to Danger: Diabolik is right up there with the Jokerís ďI think you and I are destined to do this foreverĒ in The Dark Knight.

With this review, I join my fellow B-Masters in celebrating producer Dino De Laurentiis, the schlock-movie titan who married the slapdash, try-anything audacity of the Italian cinema industry to the megalomania of Hollywood. Click the link below to read my colleaguesí thoughts on the subject.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact