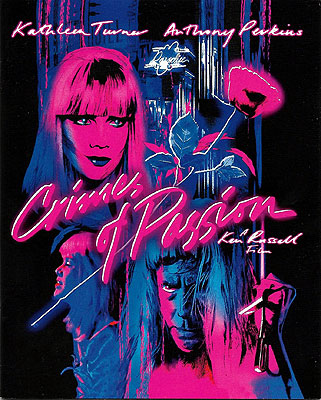

Crimes of Passion (1984) ***

Crimes of Passion (1984) ***

I’m accustomed to thinking of erotic thrillers as primarily a phenomenon of the 1990’s— which they are, provided we recognize how much work “primarily” is doing in that sentence. The 90’s were the decade when erotic thrillers fully emerged as both a genre and a marketing category, and when they proliferated not only on theater screens, but even more so on home video and late-night cable television. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that in their heyday, erotic thrillers all but replaced conventional softcore smut in all three venues. As usual, though, there are a few films made prior to the codification of the genre that deserve to be retroactively included in it on at least a provisional basis— movies that weren’t understood as erotic thrillers in their own time, but which rather do look like they belong in that box now that we have it. Even so, most of those pre-Erotic Thriller erotic thrillers can be thought of more validly as belonging to some other taxon. Dressed to Kill, for example, might be interpreted as an erotic thriller, but it’s clearly psycho-horror first and foremost. Body Heat could be an erotic thriller, but it’s definitely a neo-noir. Cruising is arguably a rare example of the gay erotic thriller, but it’s mainly a police procedural. Then, on the other hand, there’s Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion. Although it predates by several years the genrefication event marked by the successive releases of Fatal Attraction, Night Eyes, and Basic Instinct, Crimes of Passion is virtually incomprehensible except as an erotic thriller. When critics, classification boards, censorship authorities, and even its own distributor recoiled from Crimes of Passion as an unprecedented intrusion of pornographic sensibilities into the previously respectable realm of psychological suspense, they weren’t entirely wrong. But because Russell had the foresight to include in his contract with New World Pictures a clause stipulating an uncut release on home video, there was ultimately very little that the Guardians of Good Taste could do about it. And in a denouement that I find extremely gratifying, the stridently ribald unexpurgated version was a huge hit by the standards of its young medium, while the bowdlerized theatrical cut was a dud at the box office. The erotic thriller’s time might not have come quite yet, but Crimes of Passion served notice that it was on the way.

Bobby Grady (John Laughlin, from Storm Trooper and The Hills Have Eyes, Part 2) was a charismatic class clown in college, but he’s grown up since then to become the species of everyman putz familiar from a thousand noir pictures, neo-, meso-, and paleo- alike. A businessman and a family man, he hasn’t been half as successful in either capacity as he’s allowed himself to believe. On the professional side, although his electronics repair shop keeps a roof over both its own head and Grady’s, it has never quite managed to support the upper-middle-class consumer lifestyle to which he aspires— and to which his wife, Amy (Annie Potts, of Ghostbusters and the TV version of The Man Who Fell to Earth), aspires even more than him. Then on the home front, Amy is perpetually bored, frustrated, unfulfilled, and increasingly resentful, without apparently having any clear idea of what it would take to satisfy her. Nevertheless, she seems pretty sure that whatever is wrong in her life, it’s probably her husband’s fault. Amy’s vindictiveness extends even to parenting, convinced as she is that Jimmy (Seth Wagerman) and Lisa (Christina Lange) both love their father more than they do her. Bobby, for his part, must be subconsciously aware of his troubles, because we meet him while he’s tagging along with his longtime friend, Donny Hopper (Bruce Davison, from Willard and Steel and Lace), at a meeting of the latter man’s encounter therapy group. But if you were to ask Grady point-blank, he’d tell you that he’s pretty much perfectly happy. Okay, maybe he wishes his wife would put out a little more, but who doesn’t, right?

One of Amy’s more insistent consumer fantasies at the moment concerns adding a hot tub to their suburban domicile. Bobby’s inability to see how his current income might be stretched to permit such a thing leads him to a fateful decision. A friend of a friend by the name of Lou Bateman (Norman Burton, from Hand of Death and Simon, King of the Witches) runs a profitable second-string fashion house, but has come to believe that somebody in his employ is leaking designs under development to his competitors. Bateman thinks he has a pretty good idea who the culprit is, too. About three years ago, he hired a designer named Joanna Crane (Serial Mom’s Kathleen Turner, who in true Ken Russell fashion got the part not on the strength of her star-making performance in Body Heat, but because Russell loved her in The Man with Two Brains). She’s extremely talented and incredibly driven, but Bateman doesn’t trust her for reasons he can’t clearly articulate even to himself. Something to do with her above-and-beyond work ethic and the almost fanatical way in which she guards her privacy. The upshot is that Lou wants somebody to keep tabs on Joanna while she’s off the clock— to find out where she goes, what she does, whom she sees. Maybe even to catch her in the act of selling spring styles to some other firm, you know? Your guess is as good as mine regarding why Bateman would entrust such an important job to a guy who fixes hi-fis for a living instead of hiring a private eye, but Grady can have the gig if he wants it.

What Bobby learns while scoping out Joanna is nothing like what he was expecting— or what Lou Bateman was expecting, either. She’s got a secret, alright, but instead of acting as a corporate double agent, she’s moonlighting as a freelance whore! Her abilities as a seamstress and a fashion designer clearly come in handy on her second job, too, because her main stock in trade as “China Blue” is fantasy roleplay. You want to fuck a naughty nun or a sexy nurse or an outlaw biker mama? China Blue has you covered. She’ll dom, she’ll sub, she’ll play the victim in elaborate stalk-and-rape scenarios— whatever your imagination contrives to get your prick hard, there’s a good chance that she’s got a version of it hanging in the closet of the flophouse hotel room that serves as her nighttime base of operations. As for the stolen clothing designs, that turns out to have been the work of Phil Chambers (Thomas Murphy, of Death Becomes Her and The Abductors), Bateman’s most trusted lieutenant and closest friend. Bobby never so much as uncovers a hint of Phil’s activities, either; the guilty man is driven to confess by the unappeasable nagging of his own conscience.

Of course, by the time that happens, Grady has seen enough of Joanna Crane and China Blue to become fascinated by both personas, and to crave the excitement that such a woman seems to offer in contrast to the loveless, sexless marriage which he’s finally starting to recognize for what it is. Eventually, Bobby takes the next logical step, and becomes one of China’s clients. Furthermore, he ends up falling for what he takes to be the woman behind the ever-shifting mask while he’s at it. The implications for his relationships with Amy and the kids should be obvious, but there’s actually an even bigger hazard which Grady, despite his previous observation of Crane, has failed to appreciate. He’s not the only one who’s been watching her, you see, or who has recently taken it upon himself to start paying for her company. The other man is Peter Shayne (Anthony Perkins, from Psycho and The Sins of Dorian Gray), a deranged street-corner preacher with a custom-made, stainless steel murder-dildo which he’s been trying to work up the nerve to use on some of the strippers and prostitutes whom he monitors so obsessively from atop his collapsible podium while ranting at passing raincoaters about sin and divine judgment. With the inscrutable logic of the mad, Shayne has made it his special mission to bring China Blue to God. But as every Medieval witch-hunter knew, God has never been particular about requiring that sinners be brought to him alive. Indeed, sometimes he downright prefers them the other way. Now Shayne doesn’t give a shit about Grady in and of himself, but the more time Bobby spends with China Blue (or for that matter, with Joanna), scratching his itch for adventure while trying to plumb the mysteries of her dual identity, the better the chance that Peter will decide that he’s getting in the way of Holy Work.

There’s an important respect in which the foregoing synopsis is wildly misleading: I’ve made it sound like this movie is about Bobby Grady. To be sure, he’s an important character, and the viewpoint character in not quite half of the film’s scenes. He’s the character whose actions drive most of the plot. And he’s the character whom we’re permitted to understand best when all is said and done. Russell and screenwriter Barry Sandler even give him the literal last word, delivered before another meeting of Donny Hopper’s encounter group. But the figure at the center of the story, whose point of view the film shares most frequently, is Joanna Crane— usually in her guise as China Blue. Every man who meets Joanna does what he does subsequently because of some narrative that he has invented around her, having much more to do with his own desires, insecurities, and neuroses than with any actuality of her. Bateman, Grady, Shayne— without recognizing it, they’re all trying to do for free what China Blue’s customers have to pay good money for. And most importantly, it’s Joanna’s experience that makes Crimes of Passion a smutty thriller instead of a smutty relationship drama, thanks to the increasingly malign attentions of Peter Shayne. Any truly Joanna-centric attempt to boil the story down to a couple pages of text would yield utter nonsense, however, because Crimes of Passion’s plot is basically a succession of unasked-for things that happen to Crane while she’s just trying to mind her own scandalous business. That’s a big part of what makes this movie compelling and disorienting in equal measure. From the opening triptych (which serially introduces Peter, Joanna, and Bobby without offering the slightest hint of what they might have to do with each other) to that last encounter group session (in which Bobby describes a resolution to his romantic triangle that we never actually get to see, practically without reference to Amy or the children), Crimes of Passion nonchalantly violates one longstanding assumption about cinematic storytelling after another.

The most striking such violation, of course, is that we’re never really given any insight into what motivates three of Crimes of Passion’s four principal characters. What’s more, the one whose motivations are apparent is entirely banal and boring, trivially easy to understand even without the time and attention that the film devotes to him. Bobby simply grew up without ever maturing, and has coasted along for a decade or more on a plan for the future that he made when he was eighteen years old, never looking closely at how or indeed whether that plan remained relevant to the actual life that grew out of it. We’ve all met this guy, haven’t we? In contrast, Joanna, Peter, and even Amy remain complete mysteries. What on Earth could make a rising-star designer at “the biggest fashion house outside of New York” spend her nights turning tricks in the skuzziest part of the city? It seems clear that some kind of trauma lies in back of it, but every clue we’re offered as to the specifics comes from China Blue, speaking to a customer while in character as whatever she’s being paid to be. Not a word of such utterances is to be trusted, any more than we should believe anything the Joker says about how he got those scars in The Dark Knight. As for Shayne, is he a just a broken-brained bum who started festooning his preexisting insanity with crosses and crowns of thorns after he got religion? Or did he use to do this for a living? Is there some church out there that gave him the boot for behavior too heinous to be tolerated by even an Evangelical congregation? Russell and Sandler aren’t telling. The questions surrounding Amy are in a sense the most noteworthy, however, precisely because the answers are surely as prosaic as what makes Bobby tick. In fact, a number of scenes actually were shot in which Amy got to speak for herself, both in conversations with various female friends and even once in confrontation with Joanna. Russell ended up cutting all that stuff, though, and having seen the footage as a bonus feature on the Arrow Video Blu-Ray, I think he was absolutely right to do it. That’s because Bobby’s inability to understand his spouse is crucial to explaining why he burns the last ten years of his life to the ground, and almost gets himself killed by a psychotic street preacher in the process. If we were privy to Amy’s totally ordinary and unremarkable motives, it would be all too easy to dismiss Bobby as an idiot for being unable to figure her out. But by making her as uncommunicative toward us as she is toward her husband, Russell demonstrates how opaque she really is.

Okay, so now let’s dismiss English class, and start dealing with that unprecedented melding of suspense and pornography that we were talking about before. Most of the Ken Russell movies I’ve seen have been astonishingly horny, and even more astonishingly unapologetic about it. Even within Russell’s filmography, however, Crimes of Passion is way up in the right tail of the bell curve. I mean, there’s some wild shit in Lisztomania and Lair of the White Worm, for example, but neither one of them has Kathleen Turner sodomizing a cop with his own nightstick. Neither one of them has a beauty queen pageant acceptance speech delivered over the head of a guy with his face buried in “Miss Liberty’s” crotch. Neither one of them has a whore dressed as a nun taunting a purported man of God with a fetishistically fascistic rendition of “Onward, Christian Soldiers” while she parade marches back and forth atop a flophouse bed. (Although, come to think of it, I wouldn’t be all that surprised if The Devils did.) I think it’s important, too, for the film’s impact that it is someone like Turner— and not, say, Sylvia Kristel or Amanda Donohoe— committing all these outlandish sexual transgressions. Remember that 1984 was also the year of Romancing the Stone, which preceded Crimes of Passion into release by more than six months. Imagine someone who enjoyed the former movie going to see this one, knowing only that Turner was in it! Even someone who knew Turner from Body Heat could claim with some justification to be shocked by Crimes of Passion. After all, Body Heat, however overtly and explicitly sexy it could get, was never perverted. With all that in mind, then, it does rather throw me that Crimes of Passion found such profitable reception on home video. That tends to suggest that the id of 1980’s America was much darker and weirder than I’d given it credit for.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact