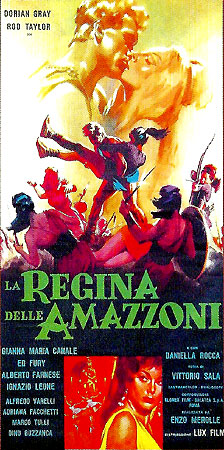

Colossus and the Amazon Queen / Colossus and the Amazons / La Regina delle Amazzoni (1960/1964) -**½

Colossus and the Amazon Queen / Colossus and the Amazons / La Regina delle Amazzoni (1960/1964) -**½

Scant moments into Colossus and the Amazon Queen— before the opening credits had quite wrapped up, as a matter of fact— something happened that forced me to reevaluate nearly all of my prior suppositions about the film. Right about when director Vittorio Sala’s name appeared on the screen, the brassy, bombastic “heroic adventure” music that had hitherto been playing was replaced by a bar or two of a new cue more appropriate to a movie in which Buster Keaton has to negotiate six blocks of city sidewalk while dodging a ceaseless rain of heavy objects dropped by klutzes from the windows, balconies, and scaffoldings overhead. “Wait a minute,” I thought. “Is this going to be a comedy?!” Indeed it was. To be sure, I was aware already that at least a few “funny” peplums existed, but the ones I knew of were all crossover parodies in which some deadly comedian like Franco and Ciccio or Toto poked fun at the burgeoning sword-and-sandal craze by applying their standard shtick to the genre. That, fortunately, is not this movie’s modus operandi at all. Rather, Colossus and the Amazon Queen is a purely organic sendup of peplum tropes, giving a legit third-tier genre star a chance to spoof his own image. And what might be even more startling to those who know a thing or two about Italian comedies of the 1960’s, Colossus and the Amazon Queen keeps almost being funny, even despite a premise that has produced more than a few truly dire films over the years.

My last remaining misconception toppled in the first substantive scene, in which a blond, brawny bruiser played by Ed Fury (most famous in these parts for portraying the eponymous hero in The Mighty Ursus and its sequels) emerges victorious from a pankration tournament that looks more like a vast, free-for-all pub donnybrook than one of the sacred athletic contests with which the ancient Greeks liked to honor their gods. Naturally this guy isn’t actually called Colossus, but to my considerable surprise, he isn’t Maciste either. Instead, he’s a character completely original to this film, by the name of Glaucus. Glaucus’s victory brings him to the attention of two merchants (Alfredo Varelli, from Duel of Champions and The Giants of Thessaly, and Gino Buzzanca, of Roland the Mighty and Maciste Against Hercules in the Vale of Woe) who say they want him to join their crew when they set sail the following morning on what promises to be an extremely lucrative voyage. The champ isn’t interested, though. He has a busy schedule of actual pub donnybrooks ahead of him, and one doesn’t win the pan-Hellenic pankration laurel crown by shirking practice.

The merchants are determined to have Glaucus, however, so while he pummels his way through that evening’s tavern-full of drunks, they offer a tempting deal to the one other customer who doesn’t seem to be involved in the fray, a man called Pyrrhus (Rod Taylor, from World Without End and The Birds). Not only will they solve his most immediate problem by picking up his bar tab, and thereby allowing him to get properly soused, but they’ll also reserve a berth for him on their ship tomorrow should he feel like making some real money. The catch is, the entire bargain is contingent upon Pyrrhus persuading Glaucus to come along, too. Pyrrhus says that’s no problem— and indeed it isn’t. He just whaps Glaucus on the head from behind after the brawl is over (a fate to which the big lug will succumb with astounding frequency throughout the film), and trusses him up like a thoroughly waxed and baby-oiled boar. Mind you, Glaucus causes some trouble when he awakens to find himself leagues out at sea in the morning, but Pyrrhus has an answer to that, too. He simply goes below, hacks a big enough hole in the hull that only a man of Glaucus’s exceptional strength can hold it closed, and refuses to permit any repairs to be made until the restive champion agrees to behave himself.

Funny thing about this ship, though— if there’s any cargo of value aboard, neither Pyrrhus nor Glaucus nor a sly Egyptian sailor by apt name of Sopho (Ignazio Leone, from Nights of Boccaccio and The Slave of Rome) can find it. Also, the vessel’s destination isn’t Corinth or Rhodes or Syracuse or any other notable trading city, but a little island nobody’s ever heard of, in a part of the Mediterranean that barely any of the crewmembers have ever sailed. And when the merchants and their crew make landfall, they find the beach strewn with rich food, fine wine, and a fortune in gold and jewels hugely disproportionate to anything that could imaginably be exchanged for it among the meager goods in the hold. Even so, only Sopho sees anything suspicious in all that. The rest are too busy filling their bellies and purses, and thus Sopho alone among the merchants’ recent recruits is spared when the drugs in the viands take effect. The Egyptian stays out of sight until the merchants have departed with the treasure, then drags Glaucus (for whom he’s developed some comradely affection) to safety from whatever is about to befall the other men.

What’s about to befall them, as you might have guessed from the movie’s title, is enslavement to a tribe of fierce and warlike women. But because Colossus and the Amazon Queen is both European and a comedy, it’s unusually frank about the sexual subtext of all the standard Girl Tribe clichés on the one hand, and unusually overt about playing them up to the point of absurdity on the other. In most respects, Amazon society is rather like a gender-flipped and stridently heterosexual version of Sparta in the 5th century BC. Its all-female ruling caste consists of nothing but warriors and stateswomen (the latter of whom presumably were warriors when they were younger), who do no productive labor of any kind. Their husbands, meanwhile, handle the cooking, cleaning, child-rearing, manufacture and repair of textiles, and so forth, but a lifetime of what an ancient Greek (or a 1960’s Italian, for that matter) would consider women’s work has left them all so thoroughly emasculated as to be pretty much useless for any task in the domain of traditional manlihood. When the Amazons need someone to open their amphorae for them, they must look elsewhere— and that’s where the merchants and their gullible sailors come in. Every so often, the former round up a crew of the latter for sale on the island to serve as something like helots, except that before the men are packed off to the mines or the fields or whatever, they have one considerably more enjoyable duty to perform. (It’s an open question whether the Amazons’ native menfolk are able to get it up for each other, but they most definitely can’t for their wives.) Pyrrhus and the others don’t realize at first what’s to become of them in the long run, however. They see only that an entire island’s worth of beautiful girls are competing over them, leading them to believe that maybe this captivity thing won’t be so bad after all.

As for Glaucus and Sopho, they meet their first Amazon when they stumble upon Antiope (The Queen of Sheba’s Dorian Gray) bathing in a secluded pond. She and Glaucus are impressed with each other’s feistiness when he does what Greek heroes usually do upon encountering a dripping-wet, nude girl, and she responds only slightly less dramatically than Greek goddesses usually do upon being approached thusly. Left to their own devices, the pair would no doubt have soon reached a mutually satisfactory resolution, but unfortunately the commotion stemming from their meeting draws the attention of Malitta (Daniela Rocca, from The Giant of Marathon and Caltiki, the Immortal Monster), for all practical purposes the Amazons’ chief of police. Malitta regards the uppity male far less favorably than Antiope, and only the latter’s stated intention to select Glaucus as her brood-stud saves him from being run through on the spot with an entire cavalry squadron’s worth of lances. Even then, neither Glaucus nor Antiope have heard the last of the matter, for Malitta tells on Glaucus at the next meeting of the Amazonian Senate. Under Amazon law, Malitta is entitled to demand the head of any man who would raise his hand against a woman— but Antiope is equally within her rights to claim Glaucus as her property, and to take sole responsibility for his discipline. Such impasses are traditionally adjudicated with a trial by combat, and this one goes soundly against the clumsy and accident-prone Malitta. But as everybody knows, settling a conflict in the eyes of the law can be something else altogether from settling it.

Malitta’s determination to see Glaucus punished by fair means or foul has more behind it than just ire at having a man stand up to her. You see, the Amazons’ queen (Gianna Maria Canale, from Conqueror of the Orient and The Devil’s Commandment) is thinking about retiring from office, and Malitta and Antiope are the women most plausibly positioned to succeed her. The queen herself favors Antiope, as does the high priestess (Adriana Facchetti, of The Wonders of Aladdin and The Sinful Nuns of St. Valentine), and Malitta is acutely conscious of their opinions. Not so surprising, then, that she’d feel vengefully inclined toward anyone and everyone associated with her rival, even if that does tend to confirm the older women’s assessment of her fitness for the throne. There’s a further complication, though. Only a virgin is eligible to rule over the Amazons, so for either claimant to take a mate among the enslaved sailors would disqualify her from accession. If Malitta knew what was good for her, in other words, she’d be encouraging Antiope to satisfy the itch in her perizoma, and nevermind Glaucus’s insubordination. Instead, though, Malitta prefers to discredit Antiope by stealing the sacred Girdle of Hippolyta— the symbol of Amazonian queenship— from the Temple of Tanith, and framing her for the crime. Glaucus’s entreaties to Antiope to run away with him to Greece will no doubt sound a lot more attractive then, right?

Malitta’s plot runs up against several concurrent obstacles, however. First, Pyrrhus happens to witness her theft of the girdle, and after re-stealing it himself from her hiding place, he uses both the artifact itself and his knowledge of Malitta’s malfeasance to blackmail her into accepting him as her he-concubine, rather than sending him on to the mines with his fellows. That coerced arrangement will have to be kept secret if the pretender is to retain any chance at the throne. Meanwhile, Antiope proves much more stubborn than Malitta expected, preferring to stand up and fight the full weight of Amazonian law and custom instead of meekly accepting her seemingly obvious defeat. The queen and high priestess are constrained by their roles from supporting her too openly, of course, but Antiope’s defiance suits them just fine. Sopho, too, is in a position to make trouble. Having never wanted anything from the Isle of the Amazons but to get the hell off of it, he’s cooking up a helot uprising. Finally, there’s a pirate crew in the area, and a chance conversation with Glaucus when they put ashore for food and fresh water gives their captain (Alberto Farnese, from The Warrior Empress and Hercules of the Desert) the idea of plundering the Amazons of their considerable riches. Any one of those entanglements is probably enough to foil Malitta’s bid for succession; all of them at once raise the prospect of permanently altering the fabric of Amazonian civilization.

If you’d like a convenient touchstone for Colossus and the Amazon Queen’s entire gestalt, just consider the costumes worn by its female warriors. I believe we’re supposed to interpret them as form-fitting chainmail bodysuits, but obviously it would have been prohibitively expensive (not to mention uncomfortable for the actresses) to make them out of actual chainmail. So instead, the Amazons of fighting age wear black leotards printed with patterns of interlocking rings in various vaguely metallic shades of blue. Unlike the knitted woolen pseudo-mail common in American and British productions of the time, it’s never faintly convincing even at a distance, but it has a certain crude charm that the more familiar method of counterfeiting chain armor lacks. The extremely flattering fit no doubt has something to do with that. But there’s also something interesting going on with the cut of the Amazons’ mail suits. The neckline plunges sharply and diagonally to the left to leave that breast (and only that one) uncovered except by the low-cut bandeau tops that the warriors wear by way of underclothes. It’s rather baffling— unless and until you remember Ephorus of Cyme’s claim that the Amazons got their name (which he derives from “amazos”— “without breasts”) because of their custom of amputating their right bosoms in order to facilitate archery. Nevermind that there’s little or no evidence of any such practice among the Eurasian steppe tribes whose coed armies gave rise to the legend of the Amazons, or that the ethnonym is more likely of Iranian origin anyway. The costume design downplaying the actresses’ right tits by calling as much attention to the left ones as turn-of-the-60’s censorship would allow is almost certainly a deliberate reference to that particular bit of ancient folk etymology. So to tally up the scorecard here, the Amazons’ outfits are at once a somewhat slipshod attempt to suggest something that the production couldn’t afford to make for real, and a jarringly erudite classical allusion, and a winking invitation to ogle some truly excellent racks. That combination is pretty much Colossus and the Amazon Queen in a nutshell.

The main thing making Colossus and the Amazon Queen as enjoyable as it is, though, is its unusual sense of humor. I can’t claim in good conscience that this movie is any smarter than the typical Italian comedy of the early 60’s, but at the same time, it isn’t as dumb, either. For starters, although Colossus and the Amazon Queen certainly has more than its share of broad slapstick, its gags of that sort get deployed in ways recognizably related to the expected business of a heroic fantasy adventure film. Thus the opening pankration tournament immediately degenerates from a solemn exhibition of athletic prowess into a mob of musclebound oafs artlessly pummeling each other, and Glaucus’s first feat of superhuman strength involves an undignified scramble to plug the hole in the hull of the merchants’ galley with his own enormous self. Thus the notionally invincible strongman displays an unbecoming vulnerability to being bopped on the head, and one of the Amazons’ ostensibly most formidable fighters is forever being bested by her own clumsiness. Even the climactic battle has a marked silly streak, as the pirates’ improvised siege engine is meant not to batter down the walls of the Amazons’ capital city, but to lob the pirates themselves over the ramparts like a sideshow human cannonball act. Similarly, although a lot of the jokes which this movie milks from the standard Girl Tribe tropes are sophomoric in the extreme, just as many of them (and often the same ones!) echo wisecracks that we’ve all made ourselves while watching the likes of Prehistoric Women and Fire Maidens of Outer Space. In my own case, the Greeks’ attitude toward being captured by an army of gorgeous females is exactly what I envisioned as the most plausible reaction to Nyah’s interplanetary boy-toy recruitment mission in Devil Girl from Mars.

But even if Colossus and the Amazon Queen isn’t as totally witless as it might seem on the surface, it still feels strange to see an actor of Rod Taylor’s standing turning up alongside Ed Fury in a film like this one. Taylor obviously thought so, too, because he was more than pleased for no one outside of Continental Europe to see Colossus and the Amazon Queen during the four years it took the movie to secure English-language distribution. (It never did get picked up for theatrical release in this country, finally limping onto US television screens as part of American International Pictures’ “Epicolor” package.) So why did he sign on in the first place? Pyrrhus would have understood his motivation perfectly. You see, this wasn’t the first time Taylor went to Italy in a professional capacity, and on the previous occasion— a location shoot for an episode of “Desilu Playhouse” at the beginning of 1960— he met and fell in love with Swedish B-bombshell Anita Ekberg. Colossus and the Amazon Queen, for him, was neither more nor less than a convenient opportunity to pick up where he and Ekberg left off that winter. Regardless of Taylor’s strictly venereal aims (and regardless of his subsequent embarrassment at the finished product), there’s very little to complain about in his performance here. Indeed, the off-camera experience of making a whole movie just to get back into his overseas girlfriend’s pants might even have benefited his portrayal of a man who inserts himself into the middle of a foreign palace intrigue for much the same reason. Taylor’s whole performance is a humongous goof, to be sure, but it’s a humongous goof to which he gave, if obviously not his all, then at least a perfectly good enough fraction of his all. Whatever else we might say about it, this role certainly stands out from the stodgy sticks in the mud that Taylor more famously played in The Birds and The Time Machine!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact