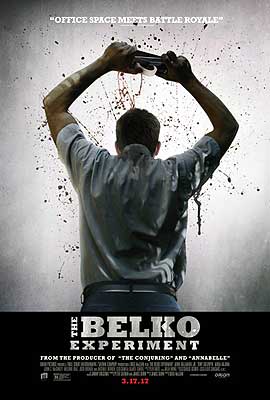

The Belko Experiment (2017) ***

The Belko Experiment (2017) ***

It always amuses me when a completed movie wears its one-liner pitch to the studio reps on its sleeve. In the case of The Belko Experiment, that pitch was obviously something like “It’s Saw meets Battle Royale in Nakatomi Plaza,” and I have to admit that would have sold me on the project, too. Given his background, it also pleases me to see James Gunn still finding the time to squeeze something like this in between Guardians of the Galaxy installments. Granted, Gunn didn’t direct The Belko Experiment (that task fell to Greg McLean, who previously helmed Rogue and Wolf Creek), but the script is his, and where Gunn is concerned, that’s usually good enough.

The eponymous Belko is a job-placement agency with a government contract (although which government isn’t altogether clear) to match American expats in Colombia with local companies in need of their skills. It’s hard to see, though, how the undertaking could be profitable. Belko has an entire tower all to itself on the outskirts of Bogota, with scores of full-time employees, even though the actual work could surely be done much more efficiently by a fraction of the personnel in a rented office suite downtown. Also, the firm’s security apparatus is a little over the top. Strictly speaking, there appear to be two security staffs— the relatively friendly indoor guards led by Evan (James Earl) down in the main lobby, and the grim, intimidating bunch who man the checkpoints surrounding the campus. Even the former have access to more firepower than they have any obvious need for, and the latter would make a fine addition to the forces of any international drug cartel or neo-Marxist insurgency. That can’t possibly have come cheap. Neither can the armored shutters on all the doors and windows, which can turn the Belko building into a veritable fortress at the touch of a button. Then there are the GPS chips. Supposedly kidnapping for ransom (especially the kidnapping of foreigners) is a favorite pastime of the local criminal gangs, and Belko’s home office requires everyone working at the Bogota branch to have tracking chips implanted in their scalps to facilitate police response in the event of their abduction. Like the onsite security, it seems both extravagantly expensive and eerily paranoid. Another funny thing about Belko’s Bogota campus (although this one ticks only the “eerily paranoid” box) is the extraordinary prevalence of former military special ops officers among the senior staff. Barry Norris the branch manager (Tony Goldwyn, from Divergent and The Last House on the Left) used to be a Green Beret, and his top lieutenants are all SEALs and Rangers and who knows what. Disturbingly, that includes even Wendell Dukes (John C. McGinley, of Intensity and Highlander II: The Quickening), the employee most likely to embroil Belko in millions of dollars’ worth of sexual harassment litigation.

One morning, Norris and his employees report to work to find something peculiar going on. The outer security cordon is looking even more paramilitary than usual, and the guards are turning away all the Colombian nationals. Only the 80 Americans on staff are waved through the gates to the parking lot. People notice, but only Mike Milch (John Gallagher Jr., from Hush and 10 Cloverfield Lane) seems especially troubled by the unexplained exclusions. Even Mike quickly gets distracted, though, by the sneakily amorous attentions of his girlfriend and coworker, Leandra Flores (Adria Arjona, of Anomalous). Much more insistently attention-getting is the voice (it belongs to Gregg Henry, from Slither and Isolation) which comes over the PA system an hour or two later, announcing that there will be “repercussions” if any two people within the Belko building are not killed posthaste. Norris tries to assure everybody that someone is merely playing a tasteless prank, but then those armored shutters snap into place, and people’s heads start exploding. There are four victims in all, chosen seemingly at random, but distributed throughout the building wherever there’s a conspicuous gathering of people. Most of the Belko staff automatically assume that they have a sniper on their hands (nevermind where a sharpshooter could be hiding inside the building), but the picture changes when Norris and his fellow ex-soldiers get a chance to examine the bodies. Those guys know gunshot wounds when they see them, and these are something else. It’s Mike who makes the connection with those GPS chips under everyone’s scalps, but when he goes to cut his out, the intercom voice sternly warns that anyone attempting to do so will have their detonators triggered. Changes Mike’s mind right quick, that does.

Knowing as we do that this movie is called The Belko Experiment, we will not be surprised to learn that these 80 unfortunates have been chosen (but by whom?) to take part in a high-stakes study of the intersection between morality and the survival instinct. The Belko employees will have two hours to produce 30 corpses from within their number; if they refuse or fail, the controllers of the experiment will kill enough of them to bring the body count to 60 instead. Unsurprisingly, all hell breaks loose once the intercom voice explains that. Some people just try to hide in the most unobtrusive spot possible until it’s all over, hoping against hope that they’ll be among the lucky ones. Others, like Bud (Michael Rooker, from Penance and The 6th Day) and Lonny (David Dastmalchian) the maintenance men, succumb to panic, and slaughter each other almost by accident. Marty the office stoner (Sean Gunn, of Tromeo and Juliet and The Hive) chooses to deny reality altogether, retreating into a paranoid fantasy about hallucinogenic chemicals in the water coolers. He even manages to attract a follower or two. But for those who keep their wits about them, it’s essentially a matter of forming up into factions behind either Mike Milch or Barry Norris. Milch advocates unity and a principled refusal to cooperate with the experiment in any way. He plausibly argues that the sickos running this circus are just going to kill everyone in the end anyway, so there’s nothing to be gained by doing the bloody work for them. Instead, he says, the Belko employees should stick together and look for a means to escape and perhaps even to fight back against their tormentors. Norris, on the other hand, goes full Realpolitik. He and his ex-military cronies, well accustomed to the idea that sometimes you simply have to accept that people are going to die, plan to break into the security guards’ weapons locker, and gain thereby the power to decide whom to sacrifice for the greater good. I’m sure they can all be trusted to do so in the fairest and most evenhanded manner possible, right? The incompatibility between the two schemes is sufficiently stark, and the stakes of the issue are sufficiently high, that the debate itself is likely to get 30 people killed before the deadline. But as Milch has already surmised, the controllers of the experiment are just getting warmed up.

The Belko Experiment appeals to me on roughly the same level as an early-80’s slasher movie, although it doesn’t much resemble one until the final act. It has the same sort of minimalist purity, with its characters forced cruelly into a kill-or-be-killed situation that only a few of them are equipped to face, whether physically, mentally, or morally. And of course the terms of that situation are such that there is neither a lot of room for depth of story nor any great need for much of it. Like the title says, the film is for all practical purposes a thought experiment examining how different personalities respond to a crisis both unjust and deadly— it’s as much a mass character study as anything else. And although it was James Gunn’s involvement that got my initial attention, this movie more properly belongs to director Greg McLean and the cast. Precisely because it is set up as a mass character study, The Belko Experiment leans heavily on the abilities of the actors, and it was a smart decision to put even minor figures like Bud into the hands of people with talent and experience. My favorite performance, though, is Tony Goldwyn’s. I was (to my surprise just as much as yours) a big fan of “Scandal” until real-world Washington insanity became too terrifying for fictional Washington insanity to be fun anymore, so I knew going in that Goldwyn’s long-running role on that show as the amoral, hormone-addled President Fitzgerald Grant III had trained him well to play appalling bastards who unshakably believe they’re always right, no matter how forcefully reality contradicts them. It’s way too plausible (and way too amusing) to imagine Barry Norris as Fitz in a parallel universe where his family never got into politics. For McLean’s part, he brings to The Belko Experiment a finely honed sensibility for the creation and management of suspense. I definitely need to dig into the stuff he made back home in Australia now. Finally, I’d like to say just a few words about the ending. It’s a curious note on which to close a film— rather like if The Cabin in the Woods had played out strictly as a rote Evil Dead copy until the final scene, and only then revealed the underground control room. The experiment is clearly much bigger and more involved than what we are shown, in a way that leaves open the potential for a genuinely satisfying sequel. At the same time, though, it works just as well if taken as a simple 70’s bummer, requiring no follow-through to be enjoyed, if that’s the right word. There’s more here if Gunn, McLean, and company would like to take it up later on, but if not, that’s just as well. It isn’t often I can say that about a modern genre movie.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact