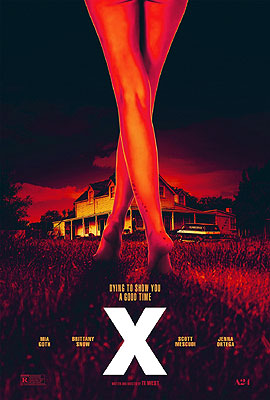

X (2022) ****

X (2022) ****

American popular culture has a real problem with the depiction of sex and sexuality right now, at virtually every level, and from seemingly every direction. Some aspects of the phenomenon are genuinely scary if you think about them for a while, looking like markers of severe, deep-seated, and persistent cultural neurosis. Consider, for example, how morgue scenes have become far and away your best bet for encountering full frontal nudity in a mainstream motion picture made during this century. But alongside such worrying symptoms is the simple fact that seemingly nobody in show business today can figure out how to handle sex in their chosen medium without pissing off someone whose money they want. Maybe that means religious bluenoses of the sort that have bedeviled all the arts since Francisco Goya’s day, or maybe it means radfem dinosaurs nostalgic for their early-80’s alliance with the Meese Commission. Lately, it might even mean Gen Z Tumblr prudes who equate the sight of a naked body in anything not explicitly marketed as pornography with being accosted by a street corner flasher, which at least offers a rush of novelty to offset the exasperation of seeing an important concept like consent misconstrued so egregiously. And that’s before we even consider the far more legitimate and cinema-specific question of why on Earth an actress should extend to any filmmaker the trust necessary for a sex scene in the context of an industry that’s been infested since day one with scumbag bonercreeps. It’s noteworthy, then, that the first movie of 2022 to grab my attention hard enough to make me go out and see it turns out to be not merely the sleazy grindhouse throwback depicted in its promotional campaign, but also an erotic horror movie in the fullest sense of the word— one in which the sex can be at least as disturbing as the violence. It’s as if writer-director Ti West heard the aforementioned Tumblr prudes griping, and said, “Okay, kids— let me show you what it really looks like when a sex scene violates your boundaries.”

Houston, 1979. Entrepreneur of randiness Wayne Gilroy (Martin Henderson, from The Ring and The Strangers: Prey at Night) has undertaken some successful ventures (like building a strip club next door to a petroleum refinery on the outskirts of town) and some unsuccessful ones (the topless car wash, for example), but he’s dead certain that this new home video thing is going to revolutionize the production, distribution, and consumption of porno movies, and he’s determined to get in on it now, while the field is wide open, and the competition practically nonexistent. With that in mind, he’s rented a cabin out in the countryside, in a place so secluded as to just about guarantee that nobody— not the cops, not his fellow smut peddlers, not even the fucking landlord— will catch wind of what he’s doing until long after his groundbreaking direct-to-video fuck-flick, The Farmer’s Daughters, is safely in the can. Gilroy wrote the script himself, and will play the titular farmer. The crew will consist of avid young film student and wannabe director R.J. Nichols (Owen Campbell, of Bitter Feast and Depraved) and his devoted girlfriend, Lorraine (Jenna Ortega, from Studio 666 and Insidious, Chapter 2). And to fill out the rest of the cast, Wayne hires his two prettiest dancers, Bobby-Lynne (Brittany Snow, of Prom Night and Would You Rather) and Maxine (Mia Goth, from Suspiria and A Cure for Wellness)— the latter of whom is also dating the boss— and a studly black Vietnam vet by the name of Jackson (Don’t Look Up’s Scott “Kid Cudi” Mescudi). Spirits run high all around (well, all around except for Lorraine, who is plainly doing this only to support R.J.) as the aspiring filmmakers depart Houston for their shooting location in the exurbs of nowhere, and there’s nary a crazy hitchhiker on the highway to spoil the mood.

No, the harbingers of doom for the cast and crew of The Farmer’s Daughters keep their powder dry until Gilroy and company reach the property which Wayne had arranged to rent. The cabin— more of a converted barn, really, now that Gilroy gets a look at it— belongs to a fellow called Howard, who looks to be about 170 years old. (Stephen Ure, who plays Howard, is merely a well-preserved 64, but has plenty of experience performing under enough CGI-enhanced makeup to render him unrecognizable, having previously portrayed orcs in The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers and its successors, and a satyr in The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.) The old coot’s memory isn’t what it used to be, and Gilroy is greeted with a double-barreled shotgun in the face when he knocks on the door of Howard’s farmhouse to check in. Evidently Howard initially mistakes Wayne for someone from “the county”— which might have something to do with the comparably ancient lady (Mia Goth again, in age makeup even more disfiguring than Ure’s) whom Maxine glimpses peering furtively at the strangers from one of the upstairs windows. Wayne eventually manages to talk Howard down, so that he and his associates can take their places in the former barn on the far side of their host’s fallow fields, but it would be a significant exaggeration to say that the old man ever warms up to his new short-term tenants. A longhair, a Latina, a black GI, and two city girls done up like a couple of whores seem unlikely to make many friends in this neck of the woods, and that probably goes double for any grown-ass white man who would consort with same. Howard leaves Wayne and the others with a declaration that he doesn’t think he likes them very much, together with a stern admonition against getting his wife, Pearl, riled up with whatever debauchery they’ve come to practice in his cabin.

What little we’ve seen of the old couple so far might naturally be interpreted to imply that Pearl is a pearl-clutcher, swift to take offense and prone to indignation over affronts to her old-fashioned, conservative values. If nothing else, the TV set in their living room is constantly tuned to the televised sermons of some ranting E-list evangelist (Simon Prast, who bears a discomfiting and probably not coincidental resemblance to Robert Englund). But as Maxine discovers when she unexpectedly meets the lady of the house after wandering off to occupy herself during the shooting of scenes that don’t involve her, the real root of Howard’s worries is something else entirely. Pearl, it turns out, had been a dancer, too, when she was young, round about the eve of the First World War. Naturally that was a very different sort of dancing than what Maxine does now, but the reputation that went along with the job hasn’t changed much at all in the intervening 60-odd years. Similarly, although Pearl never directly says so, it seems plausible enough to conclude that she became a flapper in the following decade, and subsequently kept abreast of whatever was fashionably scandalous until she finally grew too old for that sort of thing. Certainly the old dame has at least a touch of lesbianism to her, as we see shortly before she and Maxine actually meet, when Pearl spies on the girl skinny dipping in the tree-screened pond behind the cabin. What Wayne and his companions, Maxine especially, inspire in Pearl is not righteous umbrage, but a volatile mix of futile lust, helpless longing for the irretrievable past, and envy for the interlopers’ youth, health, and beauty. The end result for the pornographers is much the same in practical terms, however, for when Pearl sees something she wants but can’t have, her inclination is to destroy it— and she’s a lot less feeble than she looks! Nor can Wayne and his companions turn to Howard for any help, despite his warning upon letting them into the cabin. In the final assessment, Howard loves his wife, and if he’s too old and sick nowadays to be the man she still wants, then the least he can do is to demonstrate his continued devotion by abetting the occasional deranged sex-murder spree.

Simply put, X is the movie that Rob Zombie thinks he’s been making since 2003, without ever understanding how widely he’s been missing the mark. Not only does it offer a close approximation of authentic 70’s sleaze-horror sensibilities, but it also presents them in a period setting that is both convincing and thematically meaningful. Ti West has even thrown in a respectable amount of visual artistry, of a sort that only a few of his obvious genre models ever aspired to achieve. This is the kind of film in which a girl being pursued across a pond by an anthropophagous gator, or a fresh corpse being dry-humped by a skeletal old lady, can yield scenes and images as lyrical as they are suspenseful or repulsive.

And make no mistake, X is indeed both suspenseful and repulsive, combining the two effects in ways that I’ve been sorely missing for some considerable while. The most striking single example is a scene that occurs not long after Maxine has assumed the mantle of Final Girl, when she finds herself hiding under the bed where Pearl and Howard are taking advantage of the first erection the old man has had since probably sometime in between the two Kennedy assassinations. Maxine understandably can’t bear to remain where she is, beneath two rutting maniacs taking a quick break from trying to kill her— and in any case, the couple’s coupling is as effective a diversion as she could plausibly ask for to cover her escape. She can’t just run for the hills, however, because the killers would definitely notice her then. No, in order to make a clean getaway, Maxine will have to slip out without a single sound louder than either Howard’s grunting or Pearl’s moaning, which is going to mean taking it agonizingly slow. At the same time, though, every extra second she spends crawling across the bedroom floor is another in which one of her nemeses might happen to look her way— and that’s before we even consider how long Howard’s withered old wang can possibly last under such unaccustomed exertion. It’s been a very long time since I saw a current horror film achieve this balance of “I don’t want to see this” and “I can’t look away.”

That’s the kind of thing I was referring to before when I said that in X, sex can be at least as disturbing as violence. Pearl and Howard don’t just do terrible things. They get off on them, and eventually find a way to use them to reignite their long-extinguished sex lives. And because West shows us that outcome, and fairly explicitly at that, he also uses against us our norms and expectations about who gets portrayed as sexual beings in our entertainment media. In a culture that treats eroticism as an increasingly fraught subject even for the young, beautiful, and well adjusted, it becomes doubly shocking to see a couple of cadaverous old psychos going at it, goaded by the stimulation of taking lives. Furthermore, because it is precisely the denial of her sexuality that drives Pearl to madness in the first place, this aspect of X operates at a second level much deeper than “Ew! Look at the grody oldsters boning!” Through the thematic doubling of Mia Goth’s dual casting, we are invited at least to consider the matter from Pearl’s point of view. Pearl was once as Maxine is now, and given enough time, Maxine will inevitably find herself in Pearl’s position, physically speaking. When that day comes, do we really think Maxine will be ready to stuff her fierce libido into the attic, just because she’s grown too old to be considered hot anymore? Granted that capturing good-looking young door-to-door salesmen and torturing them to death in the basement (which appears to be one way that Pearl was getting her jollies before Gilroy and his film crew came along) is an extreme response to the problem, but I can’t really argue that the problem itself isn’t a legitimate one. (I may be peculiarly susceptible to this appeal on the villains’ behalf, as a guy who just turned 48, for whom sex has nevertheless lost none of the importance it had when he was 18…)

Now I’d like to turn your attention to the matter of X’s setting, and of that setting’s significance. It’s superficial, I suppose, for me to be as hung up as I am on the accuracy of Ti West’s simulated 1970’s, but having seen the same thing done wrong so many times by so many people, I couldn’t help but focus on it from the very first scene. My mother favored very nearly the same shade of blue eye shadow as Maxine back then (although she liked hers to have a metallic sheen), and she had friends who did the same unfortunate things to their eyebrows. Jackson’s afro is the sort that ordinary black men actually wore, not the exaggerated cranial topiary one expects to see in a modern period piece trying way too hard to tell the audience what year it is. The tube tops are the right breadth, and the short-shorts are the right length— which is to say in both cases that they’re not nearly as skimpy as they probably seemed at the time. The white men’s hair is the right degree of shaggy, while the women’s is the right degree of underwashed. Best of all, West usually shows us the shooting of The Farmer’s Daughters through the lens of R.J.’s camera, rendering the images not merely with the amount of grain appropriate to cheap 16mm film stock, but also with the strikingly warm color timing that came naturally to photographers of an era so enamored of orange, brown, beige, and gold. If you’re not sure what I’m talking about, the effect is the diametric opposite of That Damned Blue Filter. The one detail that ever feels off from the perspective of temporal verisimilitude is the alligator in the pond. Gators much bigger than adult humans were vanishingly rare in the 70’s, for the simple reason that we’d spent the past several hundred years killing all the specimens big enough to make impressive trophies. It took time for the Endangered Species Act and the shift in attitudes that went along with it to give the Deep South its monster crocodilians back. Even there, though, a suitable fan-wank explanation presents itself: since this gator plainly has an important role in covering up Pearl’s crimes, it stands to reason that Howard would strive to keep it safe from poachers.

All that said, even a pitch-perfect 70’s setting would have been no more than a stunt if all West wanted from it was an evocation of the last time when horror movies this unapologetically gritty, sleazy, and randy were commonly to be encountered. No reason it couldn’t have been a charming and effective stunt, of course, but what makes X’s period setting meaningful and memorable is how West uses it to comment on a surprising variety of subjects. To begin with what we can be sure was consciously intended, West wanted his horror movie about pornographers to celebrate the paradoxical capacity of those most mercenary and disreputable of genres to be also the most reliable refuge for filmmakers who wanted to push the boundaries of cinema by exploring taboo topics, outsider perspectives, and experimental techniques. Similarly, he wanted to remind us how often horror and porn served as in-routes to the industry for people whose circumstances might otherwise have prevented them from making movies at all. The sometimes uneasy alliance between Wayne and R.J. stands in aptly for the larger one between crass commercialism and aspiring artistry characteristic of independent exploitation filmmaking in the 70’s, while the exaggeratedly tiny scale of Gilroy’s operation calls attention to the wing-and-a-prayer basis on which the spiritual ancestors of movies like X really did tend to be made back then. Meanwhile, West and his cast do a remarkable job of capturing the mix of loutishness and likeability that one so often encounters among exploitation filmmakers active during the 70’s, together with their appealing eagerness to give the audience something wilder, weirder, and more thrilling than whatever they saw on their last trip to the theater— even and perhaps especially when their actual ability to do so wouldn’t stretch far enough to cover the check.

I think there’s a lot more to the period setting than West has openly acknowledged, however, especially when it comes to placing X in 1979 as opposed to 1972, 1976, or any other year with a seven in the tens column. 1979 was one of those “calm before the storm” years, in which momentous changes were on the horizon, but only the sharp-eyed could see them clearly. One such shift— the advent of home video normalizing pornography by moving it from the scummiest theater in town to the comfort and privacy of one’s own living room— is central to the textual premise of the film, of course, but several others are lurking in the background. The preacher on Pearl and Howard’s TV points ahead to the sexual counterrevolution of the 1980’s, while the connection between him and Maxine revealed as a surprise coda underscores both the clay-footed sordidness of televangelists like Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart, and their symbiotic relationship with the pop-culture sinners whom they made their livings condemning. Also, pay close attention to the mantras of self-affirmation that Maxine is always reciting to herself, and consider that in the end, she alone proves ruthless enough to deal with the threat posed by Pearl, her husband, and their pet alligator. Consider too that Maxine, unlike most previous Final Girls, doesn’t stick around to cooperate with the authorities after the night’s carnage has reached its end. She just calls in an anonymous tip to the sheriff’s office, and drives off in Howard’s truck to put not merely the events of the past 24 hours behind her, but apparently her whole life up to then. Whether West intended it to or not, his characterization of Maxine gives us a pretty fair parable for how the Me Decade gave way to the first of four successive Fuck You, I Got Mine Decades. Then there’s R.J.’s relationship with Lorraine, which speed-runs the whole process of evolution from sexual liberation to masculine aggrievement when the girl becomes fascinated in spite of herself with the production of The Farmer’s Daughters, and decides she wants an on-camera role as well. Again, all this stuff is subtext, and it mostly remains content to haunt your peripheral vision like a good subtext should. But it gives X a rich and varied menu of reasons for tying itself to this particular bygone era, instead of doing so merely because the film’s desired fanbase is prone to nostalgia for those days.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact