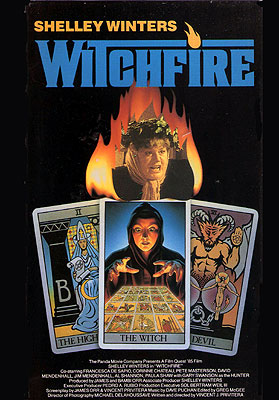

Witchfire (1985) ***

Witchfire (1985) ***

The jacket copy on the old Video Treasures VHS edition of Witchfire synopsizes it thusly:

A chance occurrence gives Lydia, Hattie, and Juliette their freedom— and a chance to prove that they aren’t crazy: they’re witches— very angry witches! Night after night, the quiet woods are witness to their mystical occult rituals. As their evil power grows, they begin a reign of terror on the nearby town. |

That… isn’t what this movie is about, even leaving aside the niggling point that the character called “Juliette” there is actually named Julietta. Weirdly, though, it probably is how the three profoundly psychotic ladies at the center of the plot would describe their story, were we in a position to ask them directly. And I can’t say I blame the Video Treasures copywriter for adopting their point of view, because it’s very difficult to imagine how else to sell this extremely peculiar little film. Part psycho-horror, part family melodrama, and part earnest and intimate examination of severe mental illness, Witchfire offers no obvious hooks for salesmanship except for the picturesque delusions of its villain-protagonists. As such, this movie is all but asking for audience disappointment— or at least for the disappointment of any normal audience. I happen to know, however, that my readers constitute a very abnormal audience indeed, so permit me to make a pitch of my own on Witchfire’s behalf: Imagine a mid-80’s episode of “The Wonderful World of Disney” about a divorced father reconnecting with his semi-estranged son via a weekend camping trip being taken hostage by a John Waters remake of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

We never see Dr. Les Larsen’s face, so it doesn’t really matter who plays him. What does matter is that he’s the head psychiatrist at the Institute for Living, an in-patient facility somewhere in rural Texas, treating people suffering from emotional, psychological, and developmental disorders, and that the inmates under his care are all devoted to him. It also matters that Larsen has just bought an expensive European sports car, which he completely lacks the experience to handle at the edge of its performance envelope. Zooming off to begin a long-deferred vacation, Larsen launches the machine right into the air while swerving to avoid a disabled vehicle, and does not survive the landing.

All the Institute for Living inmates are distraught, of course, but there are three in particular who take the doctor’s death worrisomely hard. Hattie (Francesca De Sapio) was a child of poverty and neglect, whose mother’s suicide broke her at an early age; Dr. Larsen was the only person, place, or thing on Earth of which she wasn’t too terrified to function. Julietta (Tenement’s Corinne Chateau) was habitually raped by her father throughout her childhood and adolescence, with her mother’s knowledge and apparent approval; it wouldn’t be going too far to say that she was in love with her shrink, although in her case that’s as much a symptom of her mental malady as a comment upon his effectiveness as a healer. Lydia (Shelley Winters, from Tentacles and Fanny Hill) is the real problem, though. She suffers from acute paranoia, and for some idea of the extremes of behavior to which her condition can drive her, consider how she wound up at the Institute for Living in the first place: as a teenaged girl, she got it into her head that her parents were plotting against her somehow, and burned their bedroom to a crisp with them in it to put a stop to their supposed scheming! Worse still, Lydia has quit taking her meds, unbeknownst to the institute staff, so her delusions have been gathering strength for some while.

When the news of Dr. Larsen’s death arrives, Lydia soon finds herself juggling several mutually contradictory narratives about how his disappearance is part of a conspiracy against his patients, and she’s persuasive enough a speaker (by loony bin standards) that many of her fellow inmates latch onto one or more of them as well. The most popular version among the other crazies seems to be that Larsen isn’t dead at all— that either he’s abandoned his charges and gone into hiding, or he’s being kept from them by the rest of the staff (who are of course several different flavors of evil and untrustworthy in Lydia’s telling). After just a few days, it reaches the point that Larsen’s colleague, Dr. Sally Hemmings (Paula Shaw, of Chatterbox! and Savage Streets), fears that nothing short of an outing to the funeral in the psychiatrist’s hometown of Smithville will convince her patients that Larsen is really gone. Naturally any such plan would present difficulties of its own— especially since the short-handed staff can spare only one orderly to go on the doctor’s proposed field trip— but eventually Hemmings convinces Director Jarnigan (James Mendenhall) that the alternative is even worse.

Hemmings, inevitably, has seriously underestimated Lydia. The old bat has cooked up a conspiracy of her own, rigging it so that three of the other four funeral-going inmates are in on the plot with her, and that the final slot goes to Mary (Lynn Bancroft), who, being little more than an ambulatory catatonic, will be no obstacle to her plans. Harold (Al Shannon), a patient too shy and withdrawn for anyone to suspect him of anything, will fake one of his epileptic seizures during the ceremony, distracting Hemmings and the orderly long enough for Lydia, Hattie, and Julietta to steal the institute van and escape. Then the three runaways will set up shop at what’s left of Lydia’s childhood home on the outskirts of Smithville for the final stage in the scheme. Lydia, you see, fancies herself a witch. (Bet you were wondering when that would come up, huh?) She left a stash of magical paraphernalia on the premises when she ran away from her old halfway house some years ago, so she and her companions should have everything they need to perform a summoning spell powerful enough to call forth Dr. Larsen, whichever side of the grave he might happen to be on at the moment. They’ll need to find a sacrificial victim, of course, but Lydia recalls the old homestead just crawling with rabbits, squirrels, and such even before nature got the chance to spend several decades reclaiming it.

Meanwhile, lawyer John Beggs (Gary Swanson, from The Guardian and The Bone Collector) is on his way to the same stretch of back-country nowhere with his pre-adolescent son, David (David Mendenhall, of Space Raiders). It’s John’s monthly visitation weekend with the boy, whom he intends to introduce to the manly art of recreational varmint-slaying. David, for his part, is unenthusiastic about the whole enterprise. He doesn’t see what’s supposed to be fun about shooting tiny, inoffensive woodland critters, and he’s extremely skeptical of his father’s claims about the deliciousness of rabbits and squirrels. (I can’t say one way or the other about squirrels, but rabbits definitely won their prominent place on the menu of every meadow and scrubland predator fair and square.) Beyond that, David is also just generally unhappy with his old man right now, having recently learned from his mom that John not only has a new girlfriend, but seems on track to move her into his townhouse in the not-too-distant future. Ever since the divorce, David, like many kids in his position, has harbored dearly held (if not terribly realistic) hopes of an eventual reconciliation between his parents, and the new woman in his dad’s life strikes directly at the heart of those. David passes most of the ride out to the Smithville hinterland in sullen silence, but the tension between father and son explodes just minutes after they reach their destination. Angry words are exchanged, feelings are hurt on both sides, and David takes off running into the woods, where his smaller size and greater speed and agility quickly enable him to shake off his dad’s pursuit. John’s search for the boy inevitably leads him to the ruins of Lydia’s house, and thence into the clutches of the three “witches.” Lydia gets it into her head that, despite obvious appearances to the contrary, Beggs is really a returned Dr. Larsen, and she becomes very angry at his insistence upon being someone else altogether. She’s pretty sure she and her coven-mates can devise some means of forcing him to accept his true identity, however.

As for Dr. Hemmings, she fully realizes how badly she’s screwed the pooch on this one. So, to her considerable disadvantage, does Director Jarnigan. Of course, Jarnigan also recognizes that his ass is on the line now just as much as the doctor’s, since he gave the final okay for the funeral field trip. He therefore rushes out to join Hemmings in Smithville, where they quickly enlist the aid of the local sheriff (Peter Masterson, from The Stepford Wives and The Exorcist). Alas, this guy is the second-bluntest knife in the entire drawer, surpassed only by his chief deputy (Ron Jackson, who may or may not be the same Ron Jackson that was in Play Dead and Night Game; that Jackson is a Texas boy, so it’s at least within the realm of possibility). It is, to say the very least, an open question whether the cops will be any more effective at finding the escapees than Hemmings and Jarnigan have been thus far. Indeed, the best chance for the loonies’ recapture— and for John Beggs’s survival as well— might be David, who grasps at once that something untoward is up when he returns to the campsite, and finds no trace of his father. It doesn’t take him long to follow his dad’s tracks to the site of his captivity, and while one pubescent boy is obviously no match for Lydia and her coven in a direct confrontation, we’ve already seen that David is a fairly resourceful kid. If he could stay one step ahead of his old man all afternoon, he might be able to keep one step ahead of the wannabe witches, too.

It should be obvious that any horror movie’s core subject, whatever else it may be about both on and below the surface, is fear. Certainly that means the protagonist’s fear, and in all but a very few cases it means the victims’ fear as well. More often than not, it also means the fears that are floating free in the culture at the time the movie is made. And if the filmmakers are very, very good at their jobs, it might even succeed in meaning the audience’s fear, too. Witchfire, however, is intensely concerned with a different sort of fear altogether. In a way that I’ve rarely seen anywhere else, this movie is about the fears of its villains. As Hemmings is at pains to explain to Jarnigan and the sheriff, everything the three “witches” do is driven by fear. Hattie’s main symptom is anxiety, rising toward paralyzing terror with each dose of her meds that she skips. Julietta’s madness is shot through with fear of sexual desire, both her own and that which others might bring to bear on her. Lydia has her paranoid delusions, and although her wild rages are meant to mask this, it’s plain enough that she’s scared to death all the time of her imaginary persecutors. But most of all, the women are desperately afraid that they’ll be lost without Dr. Larsen, who alone truly understands them, and who alone, so far as they’re concerned, ever could. Whereas most horror movie maniacs are predators, this bunch are driven to lethal violence by their all-consuming panic at the prospect of becoming prey— and they’re all the more deadly for the fact that no such danger actually confronts them.

Unsurprisingly, then, Witchfire’s greatest strength is the sensitivity with which cowriter-director Jim Privitera handles Lydia, Hattie, and Julietta, even at their most floridly deranged. It seems a wild claim to make about a movie in which three escaped mental patients abduct a man and attempt alternately to torture him into admitting to be someone he isn’t, and to conjure the spirit of the person they’d prefer him to be into his body, but Witchfire displays an extraordinary amount of compassion for the severely psychotic. To be sure, Privitera does revel in the strangeness of the Institute for Living inmates, to the point that this movie teeters constantly on the brink of camp. Nowhere is that more apparent than in the van ride to the cemetery, which the four passengers capable of carrying on a conversation spend bickering bizarrely like unruly, oversized children. But much as Tod Browning did in Freaks, Privitera simultaneously invites us to imagine the experience of being these people, trapped by their misshapen minds in an existence which they can neither meaningfully control nor even reliably understand. I might turn to imaginary witchcraft, too, if I had to lead Lydia’s life!

Speaking of Lydia, although I was initially surprised to see Shelley Winters credited as Witchfire’s associate producer, it made perfect sense once I’d seen the film in its entirety. Lydia, in her warped way, is a dream role for an actress on her way down post-stardom. Who Slew Auntie Roo? notwithstanding, Winters had been a little too young to get her Baby Jane on to full effect during the heyday of hagsploitation, when every faded ex-starlet in the business got a chance to cut loose in ways traditionally denied to actresses with leading-lady images to maintain. She more than makes up for the lost time here, to the degree that Witchfire often verges on becoming her one-woman show on the theme of complete psychological meltdown. Rarely a scene goes by after Larsen’s fatal wreck in which Winters doesn’t show that she could ham it up with the best of them. She blusters; she blubbers; she rages; she spews irrelevant profanity. She abuses friend and foe alike, in ever more extravagant terms, as Lydia progressively loses the ability to tell the difference. She reminded me a lot of my maternal grandmother in the final years of her life, becoming increasingly prone to volcanic outpourings of irrational spite as Alzheimer’s disease devoured her personality. And as that ought to imply, Winters accomplishes here the vanishingly rare feat of being pitiful and alarming at the same time. Witchfire won’t do the trick when you’re in the mood for any slightly conventional horror film (let alone for the one that it poses as on the back of the box), but it’s well worth a look when you want something memorably odd instead.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact