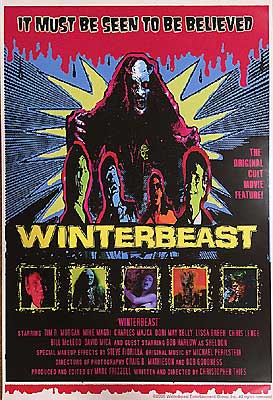

Winterbeast (1992) -*½

Winterbeast (1992) -*½

It’s tough out there for a backyard auteur, and it always has been. It may never have been tougher, though, than in 1985, when producer Mark Frizzell and writer/director Christopher Thies got it into their heads to make Winterbeast, shooting in a variety of out-of-the-way locations in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Photographic lab costs had skyrocketed over the past several years, and were still on the way up. The drive-ins were dying, the land they occupied too tempting a commodity in an era of rampant real estate speculation. Independently owned neighborhood theaters were dying, too, strangled by the proliferation of mall-oriented suburban multiplex chains. AIDS and crack were turning Times Square into an environment fit only for degenerates and criminals, and the grindhouses consequently were either closing their doors or losing interest in anything other than hardcore pornography. Even independent UHF television stations— the venue of last resort for filmmakers like Don Dohler and Bill Rebane— were on the way out, either being gobbled up as affiliates for the new Fox network or going dark altogether due to competition from the more attractive niche programming available on cable. Eventually, the burgeoning home video market would open up new opportunities, but the heyday of direct-to-video still lay years in the future in 1985. And then for Frizzell and Thies specifically, we can add all the unique challenges that confront first-time filmmakers in places with little or no history of local cinematic production, and thus little or no pool of knowledge and experience for novices to draw on. They’d have no choice but to make all their own mistakes firsthand, and learn all their lessons the hard and expensive way. No one should be surprised, then, that the quick turnaround envisioned at first by Frizzell and Thies for Winterbeast proved illusory, but even so, it’s astounding that it took them until 1992 to drag this movie before a paying audience.

It’s worth looking at Winterbeast’s oft-interrupted production in some detail, because there’s no accounting otherwise for the film’s bizarre malformation. Principal photography proceeded in weekend dribs and drabs all the way into 1989, but even then it’s plain enough that Thies never got around to filming everything he originally meant to. Meanwhile, it seems equally clear that years-old scenes which had lost their natural place in Winterbeast’s narrative as it evolved over time got included in the final cut anyway, simply because they existed. The multitude of labor-intensive special effects inserts occupied the filmmakers’ time during those annoyingly long and numerous stretches when the regular cast and crew’s day-job schedules couldn’t be brought into alignment. They too were parceled out over a matter of years, which is reflected in both their wildly variable quality and the constantly shifting sensibilities displayed in the designs of the various monsters. Equipment changes throughout Winterbeast’s production meant that some of the footage was on semi-professional 16mm stock, while other pieces were on thoroughly amateur Super 8. And in the end, the finished product was not a master negative at all, but a videotape cassette to which Frizzell had the mismatched scraps of film transferred for editing over the course of 1990 and 1991. That Winterbeast exists at all is a tribute to the power of obstinacy; its incomprehensibility testifies to the virtue of knowing when to cut bait and start anew.

Park ranger Bill Whitman (Tim R. Morgan) is having a nightmare. In it, a man whom he apparently knows smilingly pulls off bits of his own flesh while the first of seven rather nifty stop-motion monsters looms up to menace Bill. Then, in what may or may not be another part of the dream, someone who may or may not be the same guy who was flensing his own face and torso a moment ago (David Majka) is killed in the woods by a sort of skull-worm puppet creature which headbangers of a certain age might recognize from Dokken’s “Burning Like a Flame” video. (The other “Burning Like a Flame” monster appears in Winterbeast, too— in two separate guises— but it’s harder to recognize, because only the underlying armature of the stop-motion puppet carried over.) It’s never directly stated what any of that is about, but careful cross-referencing of subsequent dialogue against the closing credits might (assuming you also pick up on the strong family resemblance between Skullworm’s victim and one of the other, more prominent actors whom we’ll be meeting later) enable you to intuit that the unfortunate woodsman is supposed to be Tello, one of Whitman’s subordinates at the rangers’ station. And because we’ll see Tello’s demise again later, in greater detail if not with any greater narrative justification, it seems safe to interpret death by Skullworm as a true depiction of his fate when Whitman learns, upon arriving somewhat late for his overnight shift, that the other ranger has gone missing on the locally shunned slopes of Mount Chokura.

Tello hadn’t been the only ranger up on the mountain at the time, and Whitman reasonably imagines that Bradford (Lissa Breer) ought to be able to fill in at least a detail or two about when, where, and how she lost track of him. Remarkably, however, Bradford claims to have seen and heard nothing that might shed any light on the situation. I’m not sure I believe her, though, considering that when she says that, she looks like she just got back from a date with The Evil Dead’s horny trees. Ranger Stillman (Mike Magri), for the first and only time in the film, isn’t just being a prick for the sake of prickishness when he tells Whitman that he wouldn’t be surprised if Dick Sargent (Bill McLeod), the mountain man who brought Bradford in a little while ago, had something to do with the mysterious incident. Nevertheless, Bill is content to treat Dick as merely a witness for the time being, and arranges for Sargent to show Stillman around the spot where he found Bradford first thing in the morning.

In the meantime, Whitman and Stillman pay a visit to the one outpost of human habitation on Mount Chokura— a skiing and hiking resort called the Wild Goose Lodge— to ask the aid of its proprietor, David Sheldon (Bob Harlow). Imagine Mayor Larry Vaughan if John Waters had directed Jaws instead of Stephen Spielberg, and you’ve pretty much got this guy’s number. Whitman gets no cooperation from Sheldon even when all he wants is for the staff at the lodge to keep an eye out for the missing Ranger Tello. When subsequent developments lead Bill to recommend keeping the guests of the Wild Goose Lodge away from the Mount Chokura hiking trails during the Fall Foliage Festival, the old weirdo turns downright hostile.

What sort of subsequent developments, you ask? Well, first there’s a girl who gets dragged out of her shack and killed by a tree-stump monster somewhere between one of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Ents and From Hell It Came’s Tabonga. Then there are the tiki god totem poles festooned with human skeletons that the rangers discover at the peak of Mount Chokura. Next come three campers who are waylaid in the depths of the forest by an Owlbear. Whitman loses two more rangers, too— one to a huge, black, four-armed mushroom giant that I’ve come to think of as “Matsutakus,” and the other to the reanimated corpse of one of Sheldon’s 19th-century ancestors, whose hidden grave she had discovered and disturbed. Meanwhile, a friend of Whitman’s named Charlie Perkins (Charles Majka— evidently David Majka’s real-life brother) uncovers worrisome hints of a history of demon-worship not only among the local Indians, but among the former owners of the Wild Goose Lodge property as well.

Eventually, Bill and his fellow rangers decide to have it out with Sheldon once and for all. I have no fucking idea how we’re supposed to interpret what they catch him doing when they arrive, but it involves putting on a child-sized Halloween mask (a clown, naturally) and dancing effetely around before an audience of mummified corpses to an old Victrola disc of some child-woman singing the old nursery rhyme, “Oh Dear! What Can the Matter Be?” Upon being interrupted, Sheldon admits that he was the one who invited the fiends of Mount Chokura into our reality. But before he has a chance to address the question of why he’d do such a thing, he succumbs to spontaneous human combustion. Incredibly, Whitman and company seem to think that basically resolves the matter, but four more monsters will be coming along later to set them straight.

We might think of Winterbeast as Equinox for the 1990’s. Like that earlier film, it’s too clumsy and amateurish to be good, and too disjointed and confusing even to offer much entertainment value, but there’s a strangeness about it that’s somehow compelling. Winterbeast even comes by that strangeness in the same way, having been built up in not-always-compatible layers over a matter of years. And although this is a very small thing, I got from both movies the slight, subliminal disorientation that always nags at me when the title isn’t quite right— in this case, because the beasts are emphatically plural, while the temporal setting is explicitly autumnal. The strongest point of similarity, though, is that Winterbeast, like Equinox, is easiest to appreciate as a showcase for crudely executed but wildly imaginative stop-motion animation. (For that matter, the man-in-a-suit monsters here are pretty good themselves, with the Skullworm puppet standing out as the only complete dud.) To be sure, most of Winterbeast’s creatures get significantly less screen time than I’d have liked (Treebeard Tabonga in particular is sorely underutilized), but that’s to be expected considering the laborious nature of stop-motion. What’s somewhat less excusable, although it surely does contribute to the movie’s off-kilter vibe, is how the monsters tend to appear without any immediate provocation, and to exit the film similarly without discernable cause. Only the forced-perspective ogre whose arrival signals the onset of the climax, which I take to be Mount Chokura’s namesake devil-god, gets a proper death-battle against Whitman and his remaining allies, and even then the film spends no effort to justify why that one creature’s destruction should be sufficient to put a permanent end to the region’s supernatural difficulties. Yet in spite of everything, Winterbeast feels enough like a nonsensical fever-dream that I can’t bring myself to regret the time that I spent with it, any more than I can recommend it in good conscience to anyone but the most dedicated stop-motion aficionados.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact