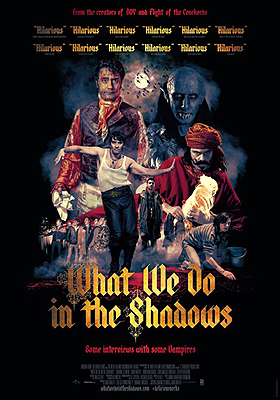

What We Do in the Shadows (2014) ****

What We Do in the Shadows (2014) ****

Perhaps you noticed, at some point during the past thirteen years or so, a short film from New Zealand making the rounds of the internet under the title, What We Do in the Shadows: Interviews with Some Vampires. Or perhaps not; heaven knows I missed it completely. Imagine an episode of “The Real World” in which all of the awful housemates are vampires living in modern-day Wellington, and you’ve got the general idea. The unifying gag of the film is summed up right at the beginning, by Vulvus the Abhorrent (co-writer/co-director Jemaine Clement): “We vampires live in the shadows, hide in the shadows, hunt in the shadows. But what else do we do in the shadows? Well, we go shopping sometimes in the shadows, or make love in the shadows.” It’s a charming enough half-hour (frankly, it’s worth it just to watch the cast attempt to speak around their ill-fitting prosthetic fangs), but one perceives at once that Clement and his partner, Taika Waititi, could have taken the premise further than they did. Obviously Clement and Waititi thought so too, because nine years later, they went back to create a feature-length What We Do in the Shadows, enlarging upon their original work in exactly the ways for which fans of the short version might have hoped. If Interviews with Some Vampires plays like a “Real World” episode, the expanded What We Do in the Shadows is more like This Is Spinal Tap with fangs.

As before, the central conceit of What We Do in the Shadows is that a small crew of documentary filmmakers have been granted leave for an exposé on New Zealand’s normally secretive undead community, focusing on four vampires flatting together in a suitably macabre old house in Wellington. Each of the housemates embodies a different vampire archetype. The reclusive Petyr (Ben Fransham, from Heavenly Creatures and 30 Days of Night) is the Count Orlock type, so ancient and corrupt that he is no longer remotely capable of passing for human, even if he could find sufficient give-a-fucks within his withered heart to try. Viago (Waititi, returning from the short version with a refined version of his original characterization) is the foppish Anne Rice sort. The friendliest and most outgoing of the quartet, he’s remarkably sunny for a guy who hasn’t seen the actual article in over 200 years. Vladislav (Clement, essentially playing Vulvus the Abhorrent again despite the change of name) is plainly modeled on Gary Oldman’s interpretation of Dracula. He’s got the hair, he’s got the moustache, and he’s got the torture chamber in the basement— although he doesn’t use that much anymore, now that he’s out of the depressive phase that lasted him most of the past several centuries. He’s even got the lingering reputation that guys who keep torture chambers usually wind up with: “My thing was poking people with various implements. I was known as ‘Vladislav the Poker’.” And Deacon (Johnny Brugh, also revisiting his role from the short) is a modernizing undead bad dude in approximately the Lost Boys-Near Dark mold— except that he was about fifteen years too old at the time of his conversion to vampirism for the nihilistic street-rat affectations to sit flatteringly on him now. Viago and Vladislav, for example, are not persuaded by his scoffing contention that vampires don’t wash dishes.

Naturally, the expanded What We Do in the Shadows spends some time recapitulating material from Interviews with Some Vampires. We get a new rendition of the housemates’ meeting to discuss Deacon’s laxness with his share of the chores. There’s a more involved dramatization of the challenges that vampires face putting together those outfits without recourse to mirrors. The montage of Viago, Vladislav, and Deacon’s night out on the town now culminates in a visit to the Big Kahuna, Wellington’s only vampire-owned hangout, where the undead are always guaranteed an invitation onto the premises. Vulvus’s rambling discussion of the other supernatural creatures than exist just beyond the sight of human beings is replaced by a pair of altercations between the vampires and the werewolf pack-cum-Men’s Movement self-help group led by Anton (Rhys Darby). And Nick the annoying newbie vampire (Cori Gonzalez-Macuer) is back as well, together with his drab yet somehow loveable software designer pal, Stu (Stu Rutherford).

But with so much more running time to fill, What We Do in the Shadows is able to include something that Interviews with Some Vampires largely eschewed: a plot. Indeed, it manages to squeeze in a whole bunch of plots running in parallel. The first is set up very early, when Viago reveals that he came to New Zealand some 70 years ago, in pursuit of the human woman whom he loved. But thanks to insufficient postage on his coffin, it took him eighteen months to complete the trip, by which point the girl had already married someone else— and far be it from Viago to interfere with his beloved’s happiness by, say, killing her husband. He’s carried the torch ever since, however, and it affects him more than he ever imagined when a chain of happenstance leads him to discover that his long-forsaken lover is now a widow, living alone in a Wellington apartment. Vladislav’s story, in contrast, is driven by undying hate. He has a nemesis, you see, a powerful and ancient vampire whom he and his housemates refer to only as “the Beast” (Elena Sejko). It sends Vladislav into a rage-sulk when the Beast is chosen over him as the guest of honor at this year’s Unholy Masquerade. And as for Deacon, his story is less about him than it is about his human familiar, Jackie (Jackie Van Beek), who is getting increasingly fed up with being strung along on promises to be granted eternal unlife at some time in the indefinite future.

Yet a fourth plot ensues when one of the victims procured by Jackie one night escapes from the lads’ feast, but runs straight into the waiting talons of Petyr. This is the revised origin of New Guy Nick, whom Viago, Vladislav, and Deacon are all chagrined to be forced to accept as an addition to their household. Nick’s whole existence is a catalog of rookie mistakes, most of them involving his habit of bragging about his undead status to anyone and everyone he meets. One such interlocutor (Brad Harding) retorts that he’s a vampire-hunter— and unfortunately for the gang, it turns out that he isn’t kidding.

I figured out very quickly that I was going to like What We Do in the Shadows, but I fell in love with it during the talking head segment in which Vladislav explains why vampires prefer to drink the blood of virgins whenever possible: “It’s like when you’re eating a sandwich. I think you would enjoy it more if nobody had fucked it.” It’s an inspired bit of vulgarity, but it’s also a comment on how muddled the thinking behind the central vampire trope has become ever since John Polidori and J. Sheridan Le Fanu reconceptualized blood-drinking as a sexual metaphor. Most of the jokes in this movie are like that, too, looking smarter the more you think about them. Given the Men’s Movement’s perennial fixation upon the cliché of the Noble Savage, there’s a twisted kind of logic to lycanthropy as the next step after Iron John. If we assume a version of vampire lore in which the undead can’t digest food other than human blood, then as a practical matter, giving up French fries might indeed be the hardest part of the transition for most people in the English-speaking world. And considering how recently Twilight was the Biggest Damn Thing among adolescent and post-adolescent girls, it only stands to reason that a pub-bro like Nick would jump instantly to the conclusion that becoming a vampire was an all-expenses-paid ticket to Pussytown. As is so often the case, the secret to good parody turns out to be taking the thing being parodied seriously enough to find all the hidden pockets of humor within it.

What We Do in the Shadows also unexpectedly excels as a character piece. Although the vampire flatmates are all archetypes first and foremost, they each (except Petyr, whose lack of personality is the whole point) have distinctive individual quirks that enrich and complicate those stock templates. Viago’s lack of guile and indefatigable good cheer, Deacon’s emotional immaturity, Vladislav’s lingering feelings of emasculation by the Beast— they all give this “exposé” something more meaningful to expose than the mere details of the vampire lifestyle, however amusing and well thought-out those details might be. Nor should we overlook the contributions of Jackie, a Renfield like no other, whose eventual turning of the tables on Deacon provides What We Do in the Shadows with some of its most satisfying scenes. (For that matter, Jackie’s impotent fuming over the “homoerotic dick-biting party” after which she must constantly clean up yields one of the film’s best and most quotable one-liners.) The movie’s secret weapon, though, is Stu, a man so perfectly boring and innocuous that he becomes paradoxically charismatic. Stu Rutherford, who plays him both here and in the original short, was not strictly speaking an actor. Clement and Waititi had wanted a genuine innocent bystander for the vampires to play against, and so hired him on the pretext that he would be working behind the camera only, as some kind of IT maintenance man. I would love to have seen his reaction the first time he got called out onto the set and told why he was really there. In any case, Rutherford’s sheer immobile awkwardness stole pretty much all of the scenes in which he appeared in Interviews with Some Vampires, so it was only to be expected that Clement and Waititi would bring him back for the long version. Crucially, Rutherford was only a little more of an actor in 2014 than he had been in 2005, and his performance still mostly consists of hanging around the periphery of the action, looking impossibly stiff and uncool. I don’t understand how it’s possible for that to be so funny and charming, but it is.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact