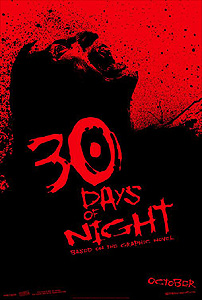

30 Days of Night (2007) ***½

30 Days of Night (2007) ***½

Fairly early on, the lead vampire in 30 Days of Night muses, “We should have come here centuries ago.” He’s referring merely to his own pack of bloodsucking fiends when he says that, but he might as well be talking about the vampire genre as a whole. Given that vampires, in most bodies of lore on the subject, have a serious problem with sunlight; given that regions above the Arctic Circle experience darkness unbroken save for short periods of dim twilight for up to six months at a stretch during the winter; given that permanent human settlements above the Arctic Circle exist in six different countries (seven if you count Greenland)— how in the hell is it possible that nobody thought to send vampires to the uppermost reaches of the globe until the 21st century?

The brilliant man who finally had that head-slappingly obvious idea was comic book writer turned would-be screenwriter Steve Niles. Astonishingly, Niles was unable to drum up any interest when he first went around pitching the premise to movie studios, and so 30 Days of Night first entered the world through his accustomed medium of comics instead, as a three-issue miniseries scripted by Niles and illustrated by Ben Templesmith. That was in 2002. A few years later, the extremely favorable reception garnered by the comic and its profusion of sequels got people in Hollywood asking themselves how they could have been so bloody stupid, with the result that 30 Days of Night eventually became what it was always supposed to have been in the first place. Rewrites by Brian Nelson and Stuart Beattie meant that it would not be quite the movie that it would have been five years earlier, but since the changes seem generally to have been in the direction of tighter focus and more streamlined plotting, that’s probably just as well anyway. Also worth the wait was director David Slade, whose breakthrough with Hard Candy would still have been years in the future had Niles managed to get this movie sold the first time around.

Barrow, Alaska— the northernmost permanently inhabited spot in the United States. 80 miles from the nearest neighboring town, inaccessible by road for much of the year, and far enough above the Arctic Circle that it never sees the sun at all from early December until about a week after New Year. That being an enormous bummer, the majority of Barrow’s 500-some residents take a month-long vacation around then, so that the population drops to as few as 150 people during the four weeks of darkness. (At this point, Pedant Man swoops down from the sky to say that Barrow, while still a tiny town, is really four times that size, and that the effectively sunless portion of the winter there lasts for 67 days, not 30.) There’s something strange going on in the background of this year’s preparation for the winter exodus, though. Somebody has broken into seemingly every house in town to steal all the cell phones. At the sled dog kennel run by John and Ally Riis (Peter Feeny and Min Windle, both of whom were in Black Sheep), prowlers slaughter the huskies on the night before the last sunrise of the year, leaving not a single dog alive. And perhaps most seriously, someone trashes the helicopter that serves as Barrow’s sole means of mechanized transport to the outside world throughout the month-long night. Sheriff Eben Oleson (Josh Hartnett, from Halloween H20 and The Faculty) and Deputy Billy Kitka (The Condemned’s Manu Bennett), who normally have nothing much to do except to break up bar fights and issue traffic and maintenance citations to Beau Brower (Mark Boone Jr., of Vampires and Frankenfish), the scofflaw Grizzly Adams wannabe who lives on the outskirts of Barrow, have their hands full with the unprecedented crime wave, and when a visibly loony drifter (Ben Foster) wanders into town shortly after the departure of the 737 carrying the bulk of the locals, Eben thinks he has some idea who might be to blame for all the recent trouble. The thing is, while one man might spirit away all of Barrow’s cell phones, he’d have a hard time making such a thorough wreck of a helicopter, and no lone human could last long against as many dogs as were killed at the Riis place. And sure enough, once Oleson gets the drifter locked up at the sheriff’s station, the only halfway-intelligible utterances he’ll make concern the certainty that They will be here soon, and that They will welcome the drifter amongst themselves when they arrive.

They are the pack of vampires that descend upon Barrow a few hours after the final sunset, preying freely and openly on the trapped and almost helpless citizens. Their leader (Danny Huston, from The Number 23) has planned this operation very carefully, using the insane drifter to scout out the area and to lay a bit of necessary groundwork to make sure that no one with a pulse will be getting in or out of the village until the undead have sated themselves. He’s even thought far enough ahead to order his followers to decapitate their victims so that the vampires will not face competition for the dwindling supply of livestock from the resurrected bodies of the livestock itself. Needless to say, no one in Barrow is even slightly prepared for such a turn of events, and the carnage during the opening hours is appalling. The two cops are obviously needed out on the streets, so it falls to Oleson’s estranged wife, Stella (Melissa George, of Dark City and the Amityville Horror remake)— who, as a state fire marshal, is at least an authority figure of some kind— to hold down the fort at the sheriff’s station, together with Eben’s fifteen-year-old brother, Jake (Mark Rendall), and grandmother, Helen (The Scarecrow’s Elizabeth McRae). While they man the radio and keep an eye on the jailed drifter, Oleson and Kitka try to shepherd as many of the townspeople as they can to something resembling safety. The sheriff’s station itself is a major target for the vampires, however, and soon Stella and Jake (Helen does not survive the attack) are forced to seek shelter wherever they can. Eben and Billy get separated, and the former winds up hiding out in an attic with Stella, Jake, Beau, and about half a dozen others. By that time, it has become inescapably plain that the creatures laying siege to Barrow are even less human than they look, and that the only hope for survival is to remain undiscovered until the sun returns in four weeks. The house below the attic hideout is not sufficiently stocked with food or water for that, however, so everybody in it understands that they’re going to have to brave the vampire-dominated streets of Barrow at some point, even before the undead begin going house to house in search of escapees.

What attracted producer Sam Raimi to 30 Days of Night was his belief that it would make for a markedly different sort of horror film from what had been commonplace in recent years. He was right. Especially in comparison to the current crop of vampire movies, 30 Days of Night is a great deal more aggressive than the majority of what we’ve seen lately, in this age when the producers of most horror films destined for theatrical release are as frightened of an R-rating as their predecessors were of an X in the early 80’s. It is as unashamedly gruesome and violent as any post-Dawn of the Dead zombie movie, and treats its heroes just as harshly. Through the Eben-Stella relationship, it demonstrates the correct way to use life-threatening duress to bring a separated couple back together, a plot template that I had long ago mentally consigned to the “nobody do this again, ever” file. It also could justly have been promoted with the tagline, “Vampires— they’re not just for goth girls anymore!” These vampires are animalistic monsters in the finest antique tradition— they’re the things that should have been surrounding Will Smith’s house in I Am Legend. They’re not pretty, not sexy, not tragic or romantic or sensitive or any of those other annoying things that vampires have tended to be since people unaccountably decided it was a good idea to emulate Anne Rice and the John Badham-Frank Langella Dracula, and oh, but it’s about fucking time! On this bunch, the modern affectation of superhuman speed, agility, and reflexes (which is normally just an excuse to have a good-guy vampire who can function as a superhero) seems completely natural and appropriate, and the filmmakers employ it the way Danny Boyle used the hyperactivity and insane hostility of the Infected in 28 Days Later… It makes the vampires too dangerous to fight except under the most favorable of circumstances. Unfortunately, Steve Niles and the two rewriters who followed him allowed that to back them into a corner at the climax, and the solution Niles adopted (which Beattie and Nelson retained) is an absurd bit of cheating dependent upon a detail of vampire biology that no one in the film has any reason even to suspect. I can tolerate a few inconsistencies, but when you introduce a new one just before the conclusion in order to make the story end the way you want it to, then something has gone seriously wrong. I won’t tell you exactly what it is that comes out of nowhere in 30 Days of Night’s waning minutes, but to get a feel for the damage it inflicts on what is otherwise an uncommonly honest and scrupulous horror movie, imagine if Ken Begg’s Hero’s Death-Battle Exemption had a drunken one-night stand with the “killer is somebody we’ve never seen before” murder-mystery cheat, and got saddled as a consequence with a club-footed halfwit lovechild. 30 Days of Night is pretty great anyway (and it at least has the courage to follow the implications of its ill-conceived endgame gambit all the way to their logical conclusion), but I still wish Niles, Beattie, and Nelson between them had been able to think of some other way out of that particular narrative box.

This review is part of a much-belated B-Masters Cabal tribute to all the living dead things that we’ve been negelecting in favor of zombies all these years. Click the link below to read all that the Cabal finally came up with to say on the subject.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact