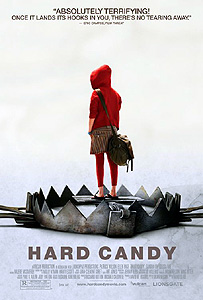

Hard Candy (2006) ****

Hard Candy (2006) ****

It’s going to be next to impossible to talk intelligently about Hard Candy without giving away practically everything about its story. Consequently, if you haven’t seen it yet, but you think you’re going to want to, then I strongly advise you to stop reading this right now, and come back only after you’ve watched the film. You see, Hard Candy is a bit more than a thriller or a horror movie in the usual senses of those terms. To an important extent, it is also a psychology experiment in which the viewer is the subject, and you wouldn’t want to queer the results by knowing the methodology ahead of time, now would you?

The first thing we see is a computer screen displaying an instant messenger conversation between Lensman319 and Thonggrrrl14. The tone of the conversation is both flirty and slightly more salacious than most people are comfortable with in face-to-face encounters, in that way that the distancing effect of internet communication so often seems to bring out. From the sound of things, the two participants have never met before, but have been maintaining an online relationship for some time. It also quickly becomes apparent that there is a significant age gap between them, and by the time Thonggrrrl14 impulsively suggests that they get together that morning for a late breakfast/early lunch at a diner called Nighthawk’s, we’ve begun to suspect that Lensman319 may in fact be much, much older than her.

He is. Lensman319 turns out to be Jeff Kohlver (Patrick Wilson), a 30-ish and slightly geeky professional photographer. Thonggrrrl14 is really Hayley Stark (Ellen Page), and she is indeed the fourteen-year-old girl suggested by the numerals at the end of her screen-name. Hayley is smart enough to exercise a little caution in this first meeting, having called her sister to report what she was doing this morning and where, and choosing a seat from which she could both survey the entire room with ease and slip stealthily out the front door in the event that she developed a bad feeling about the rendezvous. However, once initial contact is made, the girl’s guard drops precipitously, in a way that’s going to make everybody watching develop a bad feeling even if she doesn’t. Jeff is charming and solicitous, and nothing about the way he treats Hayley would seem at all creepy if they were anything like the same age. They aren’t, though, so Kohlver’s ideal-boyfriend routine is one constant clamor of alarm bells even before the conversation turns to the subject of a band Hayley said she liked, and how Jeff just happens to have acquired a bootleg recording of a recent concert that she could not attend because of her age— think of it as the 21st-century version of inviting a girl back to your apartment to see your etchings. Hayley makes a great deal of noise about how going over to Jeff’s place is so obviously not a good idea that to do so would constitute proof of insanity on her part, but then she impishly mentions that four out of the five shrinks she’s seen over the course of her short life were of the opinion that she had a thriving population of bats in her belfry. So given the expert consensus that she is insane, a visit to Jeff’s house is the only logical thing to do, right? Jeff bows before her inexorable reasoning.

More warning flares go off once the pair reach Jeff’s house. Much of Kohlver’s work turns out to be in the glamour and fashion fields, and his walls are heavily festooned with huge enlargements of such pictures. The models are all obviously teenagers, and if they were wearing any less, the photos wouldn’t be usable even for perfume ads. When Hayley asks him about his wall-art, Jeff explains that his home is also his studio, and that the mounted enlargements are thus a portfolio of sorts; when prospective models or prospective clients come to talk business with him, it is to his advantage to have representative samples of his work on display, so that the would-be customers and collaborators can see that he’s able to create the sort of images that they want. He also emphasizes that he is never alone with the models during a shoot, and that he has never become romantically involved with any of them. Well, maybe that last part is a slight exaggeration. There was one girl, way back at the beginning of his career, when Jeff was just a teenaged hobbyist himself. Her name was Janelle, and some pictures of her (reproduced on a much more modest scale than the giant art prints in the rest of the house) hang on the walls of his bedroom. Jeff claims not to have any lingering feelings for Janelle, but even Hayley can see that that isn’t precisely true. After all, one of pictures in the bedroom is dated March 19th, and Jeff’s internet handle is Lensman319. Hayley isn’t here to talk about Jeff’s ex, though. She’s looking to have some fun for herself in the here-and-now— fun like drinking up Jeff’s expensive Finnish vodka, listening to his high-end stereo at high-end volume, and starring in a Jeff Kohlver photo-shoot of her own. Oh— and also fun like dosing Jeff’s drink with sedatives raided from her surgeon father’s medical satchel. As she tells Kohlver when he regains consciousness, tied to a rolling office chair in the living room, “never drink anything you didn’t mix yourself” is good advice for anybody hanging out alone with a stranger, not just for fourteen-year-old girls.

So what’s Hayley’s game? Well, it seems she’s not quite as naïve as she looks. She knew perfectly well that Jeff’s behavior toward her was nothing like appropriate, and she’s been keeping careful tabs on him since the first time they ran into each other in that chatroom however long ago it was. She has observed his online conduct by lurking all the forums where he hangs out, and tested him by coming on to him under assumed personalities of various ages and demographic profiles. And in doing so, she has reached exactly the same conclusion as we had right at the start— this is one sleazy motherfucker. Now that she has him at her mercy, she intends to go over every square inch of his house, and ascertain whether he might be anything worse than that. Specifically, she’s pretty sure he’s a full-on pedophile, strongly suspects him of being a molester as well as a voyeur, and seems to have gotten it into her head somehow that if she searches diligently enough, she’s going to find some equivalent to John Wayne Gacy’s crawlspace. A funny thing happens when she goes digging for the evidence, though. Sure, she finds a fair amount of circumstantially incriminating stuff, but the more she turns up, the more obvious the circumstantial nature of it becomes, and the more it looks like Hayley is having herself a good, old-fashioned witch-hunt. And we all know how those usually end, right? Jeff does, too, and while Hayley is running around the house rummaging for the stash of kiddie porn or the pile of bodies she’s convinced has to be there someplace, he works on getting his legs untied. He succeeds just shortly after she does, and recognizing how screwed he is now that she’s seen the photos from his hidden safe, he goes on the attack. Kicking her savagely in the stomach, he wheels himself into his bedroom and retrieves his gun from the bed, where Hayley left it after discovering it in its usual hiding place. Thus armed, he rolls back into the living room, but Hayley, too, has found a weapon of sorts. She lunges from behind him with a roll of plastic cling wrap, mummifies his head with it, and suffocates him unconscious. Round two to Hayley.

When Jeff wakes up this time, he’s tied by bungee cords to a rolling metal workbench, his pants are missing, and there’s a big bag of ice sitting atop his genitals. An old saying about frying pans and fires springs to mind. The ice is for numbing purposes. Hayley, you see, has recognized the girl in the odd photo out from Jeff’s private stash— the non-pornographic one that was just a pretty, red-haired teenager sitting at a table outside of a coffee shop. Her name is Donna Mauer, and she’s been gracing the sides of milk cartons all over town for months. Now maybe Jeff never did anything with her except meet her for coffee, but Hayley doesn’t buy that. Besides, even if Jeff had nothing whatsoever to do with Donna’s disappearance, Hayley’s sure he was planning on raping and killing some little girl, one of these days, and thus she has taken it upon herself to perform what she calls “a little preventative maintenance.” Remember, her dad’s a surgeon; he’s got all kinds of books and instruments all over the house. Remember also that castration is a simple enough procedure that farm boys do it to horses, pigs, and steers all the time. Surely a smart girl like Hayley, with the resources she has at her disposal, can do as well on Jeff. The two of them argue the issue up and down and back and forth while she waits for the ice to do its thing, but in the end, the girl is implacable: “I’m sorry— I shouldn’t have teased you like that. I shouldn’t have let you think there was a way out of this.”

The castration scene itself is pretty amazing. It happens approximately in real time, with Hayley chattering amiably as she snips and ties, and Jeff understandably settling ever deeper into sullen defeat. It’s squirm-inducing in the extreme, and all the while, I can just about promise you that a little voice somewhere in your brain is going to be jumping up and down, hollering, “Holy shit, they went there! They actually fucking went there! What the hell, man?! You can’t fucking do shit like this in a movie anymore!” But as a matter of fact, writer Brian Nelson and director David Slade have done no such thing— the whole business has been pure psychological warfare on Hayley’s part, and when Jeff manages to free himself a second time (while his tormentor is ostensibly in the shower, scrubbing his blood off of her hands), he discovers that his thoroughly numbed balls are still right where they’re supposed to be. Kohlver plainly does not have psyops on his mind, however, when he picks up Hayley’s discarded scalpel, and goes looking for her in the bathroom. All he does is blunder into another trap, though, as Hayley shoves him into the running shower from behind, and shocks him senseless with an electric stun gun.

Jeff’s third and final return from unconsciousness finds him strung up from the ceiling in his kitchen, with a noose about his neck and his hands tied behind his back. Now Hayley explains that an innocent man, in Jeff’s position, would have run for the phone and called the cops after the bait-and-switch castration, rather than trying to attack her in the shower with a deadly weapon. Some might disagree with that reasoning, but I don’t see Hayley caring— do you? In any case, now that he’s convicted himself of Donna Mauer’s kidnapping (and presumably rape and murder) to Hayley’s satisfaction, she’s going to offer him a deal. You remember Janelle, that old girlfriend Jeff used to photograph, the one he still hasn’t gotten over? Well, Hayley found her phone number and e-mail address while going through Jeff’s stuff, and she’s got everything all set up to send her a forged e-mail “confession” from Kohlver, admitting to any and every crime that Hayley can think of to pin on him. Either Hayley can kill Jeff like she’s been looking for an excuse to do all along, in which case she’ll send that e-mail and the whole world will know what a repulsive human being he was, or he can kill himself, and she’ll spend the rest of the day erasing every trace of what happened there during the last six hours or so. He’ll be just as dead either way, but if he opts to do the honors himself, at least his memory will remain unsullied. Those remain the terms of Hayley’s bargain even throughout another round of back-and-forth table-turning, which finally culminates with the two antagonists up on the roof with a pistol and a rope, while Janelle (Jennifer Holmes, aka Odessa Rae) speeds along to the scene of the battle in response to a call from “Lieutenant Stark” reporting trouble at the Kohlver place that she might be able to defuse. And in the end, Jeff admits to almost everything: an acquaintance of his by the name of Aaron really did abduct and kill Donna Mauer, and had him over to photograph the whole process. Jeff was as bad as Hayley said he was all along. Not only that, Hayley now reveals that she subjected this guy Aaron to the same treatment a few days ago, and that Aaron put the blame for the killing proper on Jeff.

Psychologically speaking, the final act is Patrick Wilson’s big moment. Adding up all the hints from throughout the film, it appears that Jeff has been in denial about the significance of what he and Aaron did, just as he has been in denial his whole adult life about the significance of his sexual tastes. The rationalization Jeff makes to himself is that he’s just looking at pictures, or he’s just taking pictures, and so long as he never actually touches any of these girls, it’s no harm, no foul. What he has failed to accept is that even if it isn’t him, somebody is doing the touching, and by taking the pictures, or buying the pictures, or even just downloading the pictures from the internet, he makes himself complicit in their deeds. Obviously, that goes double for filming the slaying of Donna Mauer. And again psychologically speaking, Jeff’s ordeal at Hayley’s hands has its greatest importance in forcing him to scrutinize what he has done, and to see it for what it is. More than simply to punish him, Hayley wants to force Jeff to accept responsibility before he meets his fate. It comes close to backfiring on Hayley, because Jeff’s inability to recognize himself as a predator is the main thing holding him back during the early phases of their duel. Once he has accepted that his participation in the Mauer girl’s murder makes him as much a killer as the man wielding the knife, he becomes willing to do the wet work himself, and Hayley loses the advantage that comes with being even crazier than he is. Impressively, Wilson manages this transformation without making Kohlver look any less stunted and pathetic than he had been from the beginning. Kohlver thus ends up being one of the most realistic pathological killers in the annals of film.

Back in the opening paragraph, I called Hard Candy a psychology experiment. What I mean is that this movie is plainly designed to trick you into rooting for one of two complete sickos— so which do you find yourself favoring, or do your loyalties shift in one direction or the other over the course of the film? In this corner, we have a pederastic pervert and an accessory to child-killing— or possibly a straight-up child-killer, depending on whether Jeff or his partner in crime is lying about who did what to Donna Mauer. And in that corner, we have a pubescent psychopathic genius who has appointed herself Donna’s avenger for who knows what reason, and who traps two men and tortures them into committing suicide. Which of these human monsters wins your sympathy, and how long does he or she manage to hold onto it? As the above synopsis probably suggests, I personally started the movie in Hayley’s cheering section, shifted my allegiance to Jeff as it became apparent how unhinged the girl was, and then gradually pulled back to a position of fascinated neutrality.

The key to the whole trick is the filmmakers’ careful manipulation of both the evidence they present and the preconceptions of the audience. Structurally, Hard Candy is a torture-porn horror flick in the vein of Hostel or the Saw series, and it thus carries with it both the assumptions of that genre— naïve victims at the mercy of amoral lunatics who are much better organized and prepared than they are— and the taint of social opprobrium that surrounds it. But it is also a vigilante movie, which entails a very different set of assumptions: police can’t catch criminals; courts can’t convict them; prisons can’t hold them, and the sentences would be too soft even if they could; the system has failed the victims at every turn, leaving them to be victimized again and again. The two sets of genre cues directly conflict, so that none of either formula’s pat answers necessarily apply. What’s more, the emotional stakes are higher in Hard Candy, because the central issue— sexual predators targeting children— is one of modern society’s most volatile cultural and political flashpoints. That would be enough to make Hard Candy a mirror for the viewer’s psyche anyway, but the movie goes farther still by stingily parceling out the exposition. We don’t know everything that Hayley knows until the very last scene, and we never learn how she acquired most of her information. Consequently, unless you’re willing to assume uncritically that everything this deranged child suspects is true, her actions consistently seem to be at least one step beyond what the facts as we’ve seen them could possibly warrant. When she drugs Jeff, ties him to a chair, and ransacks his house for incriminating documents, all we know is that Jeff is a manipulative sleazebag. When she conducts her sham castration surgery, all we know is that Jeff has a collection of kiddie porn pictures and once photographed Donna Mauer outside a coffee shop. Only during the final confrontation up on the roof does Jeff’s actual involvement in the crime for which Hayley has been punishing him so sadistically become apparent, and by then, Hayley has crossed way too many lines for any but the most vindictive audience to say, “Oh— well, that’s alright then.” Jeff, meanwhile, has crossed too many lines for any but the most fecklessly soft-hearted to defend him.

There’s only one problem with Hard Candy, but unfortunately, it’s big enough that I can see it being a deal-breaker for some people. Hayley Stark is a lot to swallow, and although Ellen Page is extremely persuasive, there are several points when the character is not. It’s not that she seems too smart, precisely (fourteen-year-old girls can be geniuses, too, after all), but rather that she seems too sophisticated. She might know enough to devise the trap she sets for Jeff (and the presumably similar one we didn’t get to see her set for Aaron), but it’s hard to see how she could have, at her age, the life experience and the insight into human behavior necessary to orchestrate it successfully. Also, while she’s clearly in excellent physical shape (a lot of men I know would be thrilled to have Ellen Page’s abs), the size differential between her and Jeff is simply too great to make some of the things Hayley does with him believable. It doesn’t matter how many sit-ups she can do— an 80-pound girl is not going to wrangle an unconscious 160-pound man up onto a waist-high rolling workbench all by herself, let alone hoist him up and hang him from the kitchen ceiling. Hard Candy is so well constructed otherwise that the extreme unlikelihood, if not outright impossibility, of such integral pieces of the story stands out quite glaringly.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact