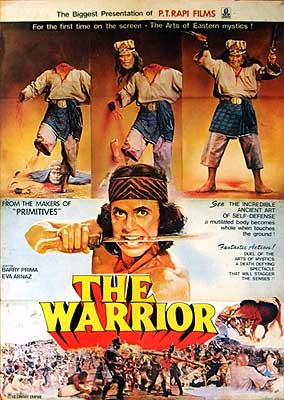

The Warrior/Jaka Sembung/Jaka Sembung Sang Penakluk (1981) -***½

The Warrior/Jaka Sembung/Jaka Sembung Sang Penakluk (1981) -***½

I wonder… If I had paid more attention to martial arts movies when I was a kid than merely to sit through the occasional broadcast of the USA Network’s “Kung Fu Theater,” might I have stumbled upon The Warrior at some point back then? It was released on home video in an English-language dub sometime in the 80’s, along with its first two sequels, The Warrior and the Blind Swordsman and The Warrior and the Ninja. I don’t know what kind of distribution those tapes received, but there were an awful lot of independent video stores in my area during the heyday of VHS, with an awful lot of real oddities haunting their shelves. Who’s to say that Indonesian anti-colonialist chopsocky flicks were not among them, evading my notice because I was too busy gorging myself on slashers, zombies, mutants, and barbarians? If I had come across The Warrior circa 1986-1988 (in retrospect one of the most fruitfully formative periods for my tastes in cinema), it might very well have made a serious fu-film fan out of me. As with all the Indonesian movies I’ve seen, it’s difficult to argue that The Warrior is especially good, but it most certainly is amazing. It’s the kind of picture that paralyzes my critical faculties with mad invention, and its mix of hyperactive enthusiasm, over-the-top (albeit crudely rendered) gore, and sheer strangeness reminds me a lot of what I found so appealing about the then-current horror films that I consumed so avidly in my teen years. Well… better late than never, right?

Believe it or not, the Netherlands were a world power from the 17th century until the collapse of European colonialism following World War II. The Dutch Empire included enclaves in Africa, the Americas, and mainland Asia, but its most extensive and valuable territories were in the islands scattered between Australia and Indochina— the lands which we now know as Indonesia. The Warrior is set in the 19th century (one source I’ve found online pins it down specifically to the 1820’s), when the Netherlands were on an imperialist rampage to reestablish their standing after two decades of vassalage to Napoleonic France. As such, the villain whose aims drive the bulk of the plot is a colonial military administrator on Java by the name of Captain Van Schramm (Dicky Zulkarnaen, of Escape from Hellhole and Virgins from Hell). He and his men have a problem in the form of a rebel known as Jaka Sembung (Barry Prima, from Ghost with Hole and The Devil’s Sword). Jaka Sembung commands no army, and thus far his followers, if such they may be called, have taken no action stronger than to organize a rent strike against their Dutch landlords, but his personal exploits as a one-man nationalist movement so inspire the Javanese natives that Van Schramm quite reasonably fears a full-scale uprising, anyway, if something isn’t done about him. And as we see when Jaka Sembung fights his way out of a prison labor camp overseen by a Dutchman (Rukman Herman, from Savage Terror and The Revenge of Samson) whom I’ll call “Lieutenant Peroxide” on account of his hilarious dye job and my inability to make out his name on either of the occasions when somebody mumbles it, the rebel’s mastery of silat makes him plenty dangerous all by himself. (At any rate, I assume Jaka Sembung is supposed to be a master of silat. Barry Prima was a karate and tae kwon do guy, though, so don’t rely on The Warrior to form your impression of what the Malay martial arts look like in practice.)

Lieutenant Peroxide’s failure to keep his hands on Jaka Sembung— whose real name, by the way, is Parmin— inspires Van Schramm to change his strategy. Instead of relying on his own soldiers for everything, the captain orders wanted posters put up all over the island, advertising a 100-guilder reward for Jaka Sembung’s capture. Those posters catch the eye of an evil silat master called Kobar (S. Parya, of The Snake Queen and Master of Kedawung), who offers his bounty-hunting services to Van Schramm at a rate considerably higher than that advertised. Kobar is clearly worth the extra money, though, since he makes his pitch by fighting his way into the captain’s villa, clobbering Van Schramm’s entire contingent of guards, and killing a bull with his bare hands. Also, he’s bulletproof, and he can breathe fire. It does indeed turn out that Parmin is no match for Kobar in a stand-up fight, but Jaka Sembung’s gifts are more than merely physical. He is able to outwit the assassin, killing Kobar through trickery and good luck when strength and fighting skill fail.

The next man to answer Van Schramm’s call is no fighter, but a magician. Ki Bidim (H. I. M. Damsyik, from Queen of Black Magic and Jungle Virgin Force) offers the captain a curious proposition. He himself has no desire to tangle with anyone as formidable as Jaka Sembung, but he knows a guy who’d be happy to take him on. The guy in question is an even more powerful warlock named Ki Hitam (W. D. Mochtar, of Mystics in Bali and Satan’s Slave), who’s been really pissed off at Jaka Sembung ever since Parmin’s silat guru, Ki Sapu Angin, decapitated him some years ago. Now most people would find beheading an insuperable obstacle to any future plans, but Ki Hitam controls a power called Rawa Rontek. That means that if any part of his body touches the ground after being cut off, it will remain alive, and can be reattached at any time. The only reason the sorcerer isn’t walking around right now is because his body was buried in one place, and his head hung in a tree elsewhere. Ki Bidim knows the location of both disposal sites, though, so for a small fee— okay, a large fee— he could have Ki Hitam back on his feet and ready for revenge by tomorrow morning. Lieutenant Peroxide thinks Ki Bidim is full of shit, but a quick demonstration of the wizard’s power convinces him and Van Schramm alike. That night, Ki Bidim proves that he’s as good as his word.

Soon thereafter, Lieutenant Peroxide leads a squad of soldiers in an unprovoked attack on a nearby village, hoping to lure Parmin out into the open. He succeeds in that much, although I somehow don’t think his original plan called for him to get killed doing it. Still, Jaka Sembung has played right into his enemies’ hands, for no sooner has he bested the lieutenant than Ki Hitam enters the fray. After as one-sided a smackdown as any in the annals of chopsocky, the bruised and bloodied Parmin is marched away in chains to Van Schramm’s villa. Not taking any chances with the extremely slippery rebel, the captain has him not merely locked in the dungeon downstairs and shackled to the wall of his cell, but nailed to it as well through the palms of his hands!

That night, a young woman in ninja attire penetrates the dungeon, and incapacitates the guards. We’re encouraged at first to believe that this is Parmin’s lover, Surti (Eva Arnaz, of Special Silencers and Five Deadly Females), who witnessed his capture, and whom we last saw attempting to drum up support for a rescue mission. However, the ninja girl is really Captain Van Schramm’s daughter, Maria (Diana Christina, from Blazing Battle and a different Revenge of the Ninja from the one you probably think of when you hear that title). Maria has long sympathized with the Indonesian people’s plight, but it took her father’s latest descent into brutality to move her to action. Unfortunately, it hasn’t moved her to fast action, and the captain catches her while she’s still explaining to Jaka Sembung that she’s come to help. Enraged by his daughter’s betrayal, Van Schramm takes it out on the prisoner. While Maria looks on, he gouges out Parmin’s eyes with a bayonet. That’s when Surti shows up— and yes, she too is dressed in an approximation of ninja garb. The trouble is, Surti even worse at covert ops than Maria, and soon winds up in the cell next to Parmin’s. Oddly, though, that turns out to be just about the best thing that could have happened under the circumstances. Blinded, beaten, and crucified though he may be, Jaka Sembung isn’t going to let any girlfriend of his languish in a Dutchman’s dungeon. He prays to Allah for strength, and Allah delivers in spades. Not only is Parmin able to de-crucify himself, but he uses his chains to pull down the whole wall behind him. Then he rips the doors off of his cell and Surti’s alike. But on second thought, maybe his prayers weren’t answered as amply as it seemed. Jaka Sembung’s Samson-strength wears off just as he and Surti come upon Ki Hitam on the villa’s front porch. The evil wizard turns Parmin into a pig, and Van Schramm’s soldiers shoot Surti as she races off after her transfigured lover.

Surti, however, is one tough chick. Although she does eventually die of her injuries, she is able to reach the forest hermitage of Ki Sapu Angin (Pursued by Sin’s Syamsuddin Syafei), who has the power to undo Ki Hitam’s spell. Ki Sapu Angin knows how to restore Parmin’s vision, too, by magically transplanting the dead girl’s eyes into his empty sockets. Then, once Jaka Sembung is fully recovered, the old guru subjects him to a new course of martial arts training calculated to give him a chance against Ki Hitam’s black magic and demonically enhanced silat. The new regimen seems to emphasize high-flying leaps and mid-air strikes with the short-bladed parang machete. There’s good reason for that, too, if you think about it. Rawa Rontek defeats death and dismemberment only if the practitioner’s corpse or body parts touch the ground, so if Jaka Sembung can kill Ki Hitam in the air, and catch his body before it falls to earth, the sorcerer will be unable to come back to life. Meanwhile, back in the village, Maria has gone full Dances with Wolves, presenting herself to Parmin’s follwers as a covert ally, and trying to organize exactly the armed mass revolt that her father most fears. It takes some of the wind out of her sails when Jaka Sembung returns home, healed, rested, and ready to fight, but this time the rebel is very much on the same page as her. Enough of rent strikes, passive resistance, and defensive Rugged Individualism. It’s time for a fucking revolution!

At first, I figured that Jaka Sembung was a genuine legendary folk hero, like Robin Hood or better yet Wong Fei Hong. In fact, however, he’s merely a comic book character, one of several who made the jump to the movies after the Suharto government’s momentous 1973 decision to prop up the Indonesian film industry with a quota system mandating that all distributors working in the country release at least one indigenous motion picture for every three imports. That is to say, Jaka Sembung is less the Indonesian Wong Fei Hong than the Indonesian Tarkan. Nevertheless, Wong seems like a fair enough touchstone for understanding the character’s appeal. Both figures embody a sort of folk nationalism that one sees again and again in cultures that were subjected to European domination during the colonial era. They use traditional wisdom and indigenous fighting arts to oppose foreign oppression in the name of peasant values, and it is the rural poor who benefit most directly from their activities. However, there’s a curious dynamic at work in the case of Jaka Sembung specifically, partly because he is a purely fictional character, and partly because his story is set at a time when a brief period of hope for an independent Indonesia was vanishing, not to return for 100 years. In an eye-opening interview appended to the Mondo Macabro DVD of The Warrior, screenwriter Imam Tantowi makes a comparison between Jaka Sembung and John Rambo. Both characters, he says, represent nationalist power fantasies, but whereas Rambo winning ‘Nam on a do-over is a fantasy of regaining lost prestige, Jaka Sembung’s rebellion is more like the “if only” scenarios that run through a crime victim’s head after they’ve been mugged. Tantowi interprets the popularity of Jaka Sembung at home as the Indonesian people sort of apologizing to themselves for their own history. It’s like Djair (who created the comics), Tantowi and Sisworo Gautama Putra (who wrote and directed The Warrior), and their Indonesian fans are saying to one another, “Look, we all know how it really was in the 19th century, but this is what should have happened.”

That sort of thinking might also explain some of The Warrior’s success overseas, at least in Southeast Asian territories like Malaysia, Hong Kong, and the Philippines. Those places had much the same experience under European colonization as Indonesia, after all. But how do we account for this movie’s modest but noticeable success in Greece, the UK, and— no, really!— the Netherlands? My guess is, those audiences related to it mainly as a gonzo exploitation action movie, because heaven knows The Warrior is one of those. For one thing, Barry Prima’s admiration for Bruce Lee is immediately apparent. He’s an impressive physical performer, a skilled martial artist, and a charismatic leading man even when hampered by dubbed dialogue composed more with an eye toward matching mouth movements than toward making any kind of syntactic or emotional sense. The entire film has a crazed energy about it, and a willingness to go places the audience would never expect. When Jaka Sembung was blinded in the second act, I immediately thought, “How the hell are they going to get out of this one?!” I might have guessed that magic would be involved, but the sorcerous transplant of Parmin’s dead girlfriend’s eyeballs would simply never have occurred to me. The transplant scene itself is a fine example of The Warrior’s “fuck it— we’ll do it anyway” approach to all the things the production couldn’t really afford. The extracted orbs appear to be actual sheep’s eyes, which makes for an alarming contrast with the craptacular prosthetic head surrounding them. A similar naïve effectiveness is achieved in Ki Hitam’s resurrection scene. The neck-stump makeup effect is of Halloween costume caliber, but I’ve never seen a more convincing short guy dressed up as a headless zombie anywhere else apart from that. Putra does an extraordinary job playing up the violation of nature that the warlock represents, too. At the other extreme, Kobar’s duel with the bull is just endearingly silly all around. It’s the most placid, least threatening animal of its kind I’ve ever seen, and the dummy bull used for stunt shots like the one where it crashes through a wall is right up there with the man in the bunny suit employed similarly in Night of the Lepus. Then there’s the makeup for the villains. Not since Tarkan vs. the Vikings have I beheld a comparable array of wigs, false beards, and trick dentures. I can’t deny, though, that after all those years’s worth of white guys with fake eyelids passed off as “Orientals” in American and British movies, it gave me a perverse thrill to see so many Indonesians in unconvincing whiteface playing the Dutch.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact