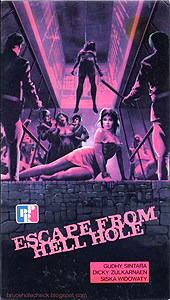

Escape from Hellhole/Hell Hole/Kawan Kontrak (1983) **˝

Escape from Hellhole/Hell Hole/Kawan Kontrak (1983) **˝

At first, I was baffled by Escape from Hellhole’s very existence. Admittedly, I’m hardly an expert on Indonesian cinema, but what I’ve seen suggests that sexploitation was not a mode it was configured to support during Suharto’s New Order era. Although Suharto’s Pancasila (or Five Principles) ideology was largely secular, and its support for a unifying monotheism couched in terms that stopped short of an overt endorsement of Islam, his government nevertheless took a hard line on questions of public morality not so very different from the prescriptions of Muslim theocrats both in Indonesia and elsewhere. If I understand the situation correctly, his motive was to placate the religious conservatives who might otherwise have coalesced into a rival power base. One result of that hard line was fairly strict censorship of sexual content in films. Explicit nudity was forbidden, although optical fogging (as in Jungle Virgin Force’s skinny-dipping scene) could sometimes be an acceptable workaround. Traditional values like modesty, chastity, and fidelity were to be encouraged, which seems in practice to have meant the tight circumscription of allowable behavior for female characters, and a consequent tendency for villainesses to become much more interesting than heroines. So all in all, Suharto’s Indonesia would seem like a fundamentally hostile environment for movies expressly devoted to titillation, and women’s prison movies on the New World Pictures model ought to have been completely beyond the pale. Thus my bafflement over Escape from Hellhole. But in checking into this movie’s background (to the extent that that’s possible for someone who knows about five words of Malay), I learned something that made at least partial sense of the situation. Escape from Hellhole wasn’t strictly of Indonesian origin, although it was shot there with a mostly indigenous cast and crew. Rather, this movie was a co-production with backers in the Philippines, where the chicks-in-chains genre as we know it was practically invented. My guess, then, is that the Filipinos inspired their Indonesian partners with promises that films like this one were reliable international moneymakers, and that bookings abroad would enable the producers to turn a profit even if Escape from Hellhole got into trouble with the censors at home. The Filipino connection could also explain the existence of the dubbed-into-English version that I saw. Even if Escape from Hellhole never made it out of the Indies until Video Asia released it as part of their bizarrely mistitled Tales of Voodoo DVD series, its producers would have been fools to ignore the sizable English-speaking market in and around Manila.

There’s one thing about Escape from Hellhole, though, that becomes more curious when you know about the Filipino involvement in its creation. At least so far as the story is concerned, the previous women’s prison movie it resembles most is not The Big Doll House, Women in Cages, or any of that lot, but rather the Brazilian Amazon Jail. That’s because instead of a legitimate penal institution, the Hellhole of the title is the secret dungeon of a brutal sex-trafficking ring. A virginal country orphan named Indri (Lina Budiarty, from Midnight Guests and Forbidden Legacy) falls into the slavers’ clutches when her old friend, Cartina (I think this might be Siska Widowaty, of War Victims), offers her a job at the home of her rich uncle, M.G. (Dicky Zulkarnaen, from The Warrior and Satan in Her). M.G. may or may not really be Cartina’s uncle, but he certainly is holding her father prisoner somewhere in his nightmarish Third World version of the Playboy Mansion, and the captive man will go free only after Cartina has supplied a certain number of girls for M.G.’s business. As for why she hands the bastard her best childhood friend from back home, Indri simply has the foul luck to fit M.G.’s bill extra-well. More than anything, what he wants for his stable is virgins. At first, I figured that was because his clients would pay extra for the privilege of devirginizing them, but actually it looks like violating maidenheads is just M.G.’s personal kink.

In any event, when Indri discovers what Cartina has gotten her into, she takes a firm enough stand to satisfy any patriarchal purity freak. She isn’t going to bed with M.G. under any circumstances, nor will anyone in his employ be laying a hand on her if she has anything to say about it. Most of the film will concern M.G.’s efforts to convince her that she hasn’t. Although the boss-man’s virgin fixation places one clear limit on what Bugle, Mario, and the rest of M.G.’s private army may do to Indri by way of softening her resolve, it’s pretty much the only limit. Imprisonment, forced labor, whipping, stress-position bondage, various forms of humiliation— they’re all fair game. Then there’s the peer pressure factor. The closest thing Indri has to a friend and protector down in the dungeon (she naturally sees Cartina in a different light now, even when M.G. double-crosses her, and makes her a prisoner too) is Helga (Leily Sarita, of Virgins from Hell and whatever movie Ferocious Female Freedom Fighters started off being), a former favorite of M.G.’s, who consistently counsels Indri that her best bet for a long and not-too-miserable life is to become M.G.’s current favorite. Eventually, Indri appears to yield to Helga’s advice, but she’s merely playing her captor. The guards bring Indri to M.G.’s suite when she announces her readiness to submit, and for a little while, the sex slaver looks like he’s about to get what he wants. Indri permits the assignation to go as far as some pretty heavy-duty making out… and then she bites off M.G.’s tongue!!!! That’s when Escape from Hellhole gets really interesting…

I hesitate to use the word “feminist” in describing a women’s prison movie; anyone who’s ever seen one will immediately understand why. Still more do I hesitate when the movie in question is explicitly built around the notion that a woman’s virginity is the most valuable thing she can ever possess. But although it would be going much too far to call Escape from Hellhole feminist, this film does seem to be groping toward a perspective not too far out of line with feminism, in a weird, sleazy, and distinctively Third World way. Perversely, the filmmakers seem to have been pushed in that direction by the strictures of the Indonesian censorship regime. That is, the rules put a fairly low ceiling on how much of a sexploitation movie Escape from Hellhole could be, forbidding many of the women’s prison genre’s more unenlightened commonplaces. No nudity means only the most cursory shower scenes and only the tamest catfights. No “sexual immorality” means no lesbianism and no seduction of guards or infirmary staff. Most of all, those twin bans combine with the requirement to encourage (or at least not to infringe upon) traditional patriarchal values to mandate a very different handling of nonconsensual sex from what you’ll see in the likes of Caged Heat or The Big Bird Cage. Women’s prison movies, as a whole, love their rape scenes, and what’s more, they tend to use them as substitutes for love scenes. That usually means trying to make rape look sexy, and often it means trying to make it look pleasurable for perpetrator and victim alike. Consider, though: if a girl is supposed to be the steward of her virginity, keeping it safe for delivery to her future husband, then the nasty “rape her ‘til she likes it” game that these films so frequently play isn’t going to fly. The victim isn’t allowed to like it, because liking it would make her a whore according to the precepts of purity culture. The audience, meanwhile, isn’t allowed to like it, either— otherwise, the filmmakers would be undermining the nation’s moral foundations. The result, paradoxically, is that Escape from Hellhole’s treatment of sexual violence looks much the same as it would in a movie that sought to attack patriarchal norms. The victim (generally Indri) always fights like a wildcat, leaving no room for interpreting the assault as anything else. There are no longing close-ups on exposed flesh to divert the viewer’s interest down the same channels as the rapist’s. We’re invited to see the coerced sex as ugly and vile, the way it really is.

That’s basically an accident, though— a case of convergent evolution. Where Escape from Hellhole really starts to look sort of haltingly quasi-feminist is in its portrayal of Indri’s developing response to her situation. Plenty of women’s prison movies end with a breakout, so I’m not awarding any points for that per se. However, in plotting and organizing the mass escape from M.G.’s dungeon, Indri begins to articulate a philosophy of solidarity against injustice, of cooperation toward bringing down M.G. and his followers for the mutual good of all the captives, and of all those who would otherwise be similarly enslaved in the future. Indri doesn’t explicitly preach rebellion against sexism, but because the wrongs she and the others have suffered are unmistakably gendered, the uprising to redress them can’t help but be gendered too, in the opposite direction. Again, this isn’t feminism, but it isn’t quite the distinctively retrograde sleaze that you see in Western takes on this premise, either.

There’s something else, too, that is almost unbelievably subversive within Escape from Hellhole’s cultural context, and that makes me respect this movie above and beyond anything its quality, as that term is usually defined, could justify on its own. In a sense, organizing the other slaves into an avenging army is not Indri’s ultimate act of rebellion. Before she can do that, she needs to establish herself as the kind of hard-ass who really could lead the captives to victory, and the way she gains that street cred is absolutely astonishing. There’s a long tradition in patriarchal cultures the world over of conceptualizing the rape of a virgin as somehow worse than killing her, and of presenting suicide as therefore the preferable, honorable option for a girl with no other hope of hanging onto her maidenhead. For a really egregious example of the idiocy that such thinking can lead to even in the supposedly enlightened West, have a look at Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s 1787 novel, Paul and Virginia, which ends with the heroine drowning herself not to avert a rape, but to prevent strange men from seeing her in her underwear! Anyway, the turning point in Indri’s character arc is set up to suggest that she has decided to follow the age-old pattern. But when the guards find her sitting on the bathroom floor in a puddle of her own blood, clutching a gore-smeared bamboo stake in her hand, it isn’t her wrists or her throat that she’s slashed. The censor presumably would not have permitted an overt statement of what harm she’s inflicted on herself, but when she contemptuously tells the guards, “M.G. can have whatever’s left of me,” the message comes across clearly enough: “Fuck you. It’s my hymen, and I’ll do whatever the hell I want with it!” Remember that this is a culture in which, traditionally at least, it most certainly isn’t her hymen; she merely holds it in trust for its true owner, whomever she ends up marrying. At the last, then, Indri agrees with Helga that her life is worth more than her so-called virtue— but she more radically promotes her bodily autonomy to a position above it, too. No wonder all the other prisoners (Helga included) suddenly start looking at her as if to say, “Damn! That chick is hardcore!”

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact