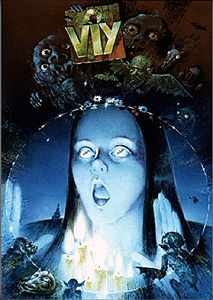

Viy/Viy, or Spirit of Evil (1967) ***½

Viy/Viy, or Spirit of Evil (1967) ***½

The Soviets never really went in for horror movies. In the early 30’s, when monster madness gripped most of the movie-producing world to one extent or another, Stalin and his minions were still waging intellectual war against peasant superstition, and films about upirs, Baba Yaga, or Vodyanoi would never have passed muster with the arbiters of Bolshevik culture. The relative liberalization under Khrushchev carved out sufficient exceptions to the formerly rigid demands of Socialist Realism to permit the rise of both science fiction and fairy-tale fantasy as cinematic genres in Soviet Union, but even then, horror movies in the Western sense remained extremely rare. In fact, the only one I know of for certain is Viy. It may be that Viy represents a Soviet recapitulation of a trend that showed up 50 years earlier in American cinema. For the first couple decades of the 20th century, horror was frowned upon here, too, but could occasionally sneak onto the screen under the cover of a sufficiently well-respected literary source. Think of D. W. Griffith building The Avenging Conscience out of ideas raided from the works of Edgar Allan Poe, or The Headless Horseman mounting one good scare at the front of an otherwise tedious adaptation of Washington Irving’s most famous tale. Viy was based on a piece by Nikolai Gogol, who along with his mentor, Aleksandr Pushkin, was a major figure in Russia’s contribution to the development of the modern short story in the early-to-mid-19th century. Gogol was a contemporary of Poe, J. Sheridan Le Fanu, and Guy de Maupassant, and like them, he often employed macabre or mysterious themes in his writing (although he was closer to Maupassant’s end of the spectrum than Poe’s when it came to the frequency with which he did so). His approval of religion, mysticism, traditional forms of authority, and even serfdom would have made his work suspect in the extreme under Lenin and Stalin, but by the late 1960’s, the Soviet system was sufficiently well established for the Communist authorities to admit that the art and literature of the Czarist period wasn’t all bad. And although “Viy” specifically was one of Gogol’s most overtly horrific tales, it wasn’t far removed in premise or tone from the antique fairy stories that had become such a rich store of source material for Soviet filmmakers since the mid-1950’s. On that note, it might also be significant that Viy’s production designer and special effects maestro was Aleksandr Ptushko, one of the foremost directors of Russian fairy tale films. With Ptushko setting the look and feel of the project, Viy would represent only an incremental push past the fantasy movies that already existed, as opposed to the radical departure that a phrase like “the first true Soviet horror movie” would otherwise seem to imply.

Don’t worry for the present about what exactly a “Viy” is; we’ll get to that in due time. Instead, let us marvel over the unlikelihood of our protagonists, a trio of young men studying to be monks at a remote, rural monastery. These are Khoma Brut (Leonid Kuravlyov, from Ivan Vasilievich: Back to the Future and The Invisible Man), Gorodets (Vladimir Salnikov), and Khaliava (Vadim Zakharchenko), and you might think of them collectively as the John Belushi of their seminary. It’s hard to know what to make of the boys’ characterization. On the one hand, such a loutish bunch of novices does dovetail nicely with official Soviet ideology on the subject of religion. On the other, affably misbehaving churchmen were something of a commonplace in Russian literature about peasant life even before the revolution. And on the left foot (because I’m all out of hands now, and I balance better on the right), Russian Orthodoxy has long been just a little less anti-fun than many other forms of Christianity. In any case, one gets the impression, watching Viy, that we’re not supposed to take “lazy, horny, drunk, and mischievous” as an entirely negative set of personality traits, even for would-be monks.

As the story begins, the novices are being released from their studies for a few days’ break. Khoma, Gorodets, and Khaliava schlep off together for a visit to their old home village, but sundown catches them still out in the open countryside. Luckily, one of them spies a cottage not too far away, where they might be able to finagle a bed for the night and maybe even a meal. The cottage belongs to a weird old lady (Ruslan and Ludmila’s Nikolai Kutuzov, acting in drag), from whom not just we, but also the three wayfarers get a distinct Torgo vibe. If nothing else, the lads feel some suspicion over their host’s determination to split them up in different parts of the house and its outbuildings. Khoma gets billeted in the stable, and it’s to him that the crone reveals her ulterior motive for taking him and his friends in. Evidently it gets lonely out there on the steppe, and a woman has needs, even at her age. Khoma doesn’t go in for grannies, though, nor is he prepared to swallow his pride and take one for the team. His strenuous efforts to rebuff the old lady’s advances avail him nothing, however, for in keeping with the obvious stereotype, she’s really a witch with hypnotic powers. And since Khoma has already refused the easy way, it only stands to reason that he’ll be getting it the hard way now instead. The witch climbs up onto the mesmerized lad’s shoulders, and proceeds to ride him through the darkened sky like an enchanted horse until the sun begins to light up the eastern horizon. Khoma is not in the best of moods when the witch permits him to land and to regain control of his body, and he immediately begins thrashing her with a convenient stick. A funny thing happens once the witch is well and truly clobbered, though. She suddenly transforms from a desiccated old hag into a beautiful girl (Natalya Varley, from Wolfhound and The Wizard of Emerald City)! Khoma sensibly picks this moment to put as much distance between him and the witch as possible, before his night (or morning, really, by this point) gets any weirder.

Naturally he won’t be escaping so easily. When Khoma returns to the monastery, the abbot (Song of the Forest’s Pyotr Vesklyarov) informs him that he has work to do. The local seigneur (Aleksei Glazygin) has a teenaged daughter, and a day or two ago, she crawled home after being beaten three-quarters to death by persons unknown. There’s basically no hope of the girl surviving, and it is her wish to receive last rites from one of the novices at the monastery— curiously, she asked for Khoma Brut by name. To Khoma’s credit, he grasps at once the significance of all that, and recognizes that a trap is being laid for him. Nevertheless, it’s hard to see what good his perceptiveness is going to do him. The abbot will brook no argument about complying with the dying girl’s wishes, and His Lordship has sent a party of men led by a tough old peasant called Yavtukh (Stepan Shkurat) to ensure that Khoma makes the proper haste to his destination. At first, it seems like Khoma has just a bit of luck on his side after all; the seigneur’s daughter never told her father who administered her fatal beating, and the girl herself succumbs to her injuries just hours before the novice’s arrival. But the grieving lord still expects Khoma to pray over his daughter’s corpse for three nights before her burial, and it turns out that death has done nothing to blunt the edge of her black magic. Each night of Khoma’s vigil is the occasion for a pitched battle of supernatural forces, culminating with the dead girl conjuring up an entire army of Hellspawn— including her personal patron from the Pit, the devil Viy.

I’m pretty thoroughly convinced that if it hadn’t been for that whole Iron Curtain thing, Aleksandr Ptushko would be as universally loved by today’s fans of fantastic cinema as Ray Harryhausen. Viy shows that even when it wasn’t him in the director’s chair, Ptushko could dominate any project with which he was associated. The movie is nifty-looking throughout, but the final night of Khoma’s vigil, when the hosts of Hell come in answer to the witch’s summons, will take your breath away. What makes Ptushko’s work doubly impressive is that it’s so technically primitive. Even his most eye-catching and memorable effects are nothing but trick photography in its purest form, supplemented here and there by models and makeup. Take away color film stock and synthetic rubber, and there’d be nothing in Viy that was beyond the technological grasp of Georges Melies, Walter Booth, or Segundo de Chomon 60 years earlier. But primitive as they are, Ptushko’s tricks rarely seem antiquated. Only the charmingly clunky monster suit representing Viy himself (which is roughly on par with a middling “Outer Limits” creature costume, for good and for ill) would be deemed unacceptable today, even if none but the most consciously nostalgic filmmakers would actually use most of these specific techniques. If nothing else, Viy is an impressive illustration of how much spectacle can be achieved by doing things the old, hard way.

For Western viewers, Viy can be a subtly, pleasantly disorienting experience. A fair bit of the cultural context doesn’t quite come through, so that it isn’t always obvious why things are happening the way they are. And even when the meaning is perfectly clear, there are still a hundred ineffable tics of foreign stylistic convention to produce frequent jolts of the unfamiliar. That’s doubly true because “clergyman vs. devil” is a plot template that any horror fan will recognize, and think they know very well. Viy’s creators didn’t share our expectations for how stories like this one are supposed to work, though, and the movie makes no effort to meet them. In a lot of ways, I’m reminded of 100 Monsters— not because Viy is more than superficially like that movie (although they do both feature unforgettable menageries of weird folkloric creatures), but because it too belongs so utterly to an alien culture that watching it is like glimpsing a complete alternate conception of what the horror genre can do and be. As I’ve said before, the chance to discover such alternate conceptions is a big part of my motivation for watching foreign films, and Viy leaves me longing for more of a cinematic tradition that just barely existed in the first place.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact