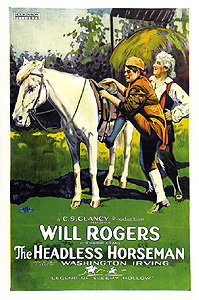

The Headless Horseman (1922) **

The Headless Horseman (1922) **

When I was little, my father used to tell me bedtime stories about the Headless Horseman of Underwood Road. Being three or four years old, I was naturally unacquainted with Washington Irving, and therefore unaware that the story had a more ancient pedigree, or that the woods to the east of Crofton, Maryland, were not its original setting. My dad’s version was more gruesome than Irving’s, too (the man knew his audience), with a flaming skull taking the place of the regulation pumpkin, and without the implied rational explanation that seemingly every retelling save Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow makes irritatingly explicit; I’d be a liar if I said I didn’t like the story better that way. That aside, I don’t think it’s just because I heard a variation on it so many times during my earliest youth that I consider The Legend of Sleepy Hollow to be one of the all-time classic American ghost stories. It’s curious, then, that despite its having been filmed several times, the only Headless Horseman movie that comes anywhere near classic status is the Disney cartoon from 1949. This early effort, for example, succeeds in capturing the spirit of the setting and recounts the plot in a more or less faithful manner, but it has no clear focus or identity and pays far too little attention to the titular phantom.

Somewhere in the New York countryside lies the little hamlet of Sleepy Hollow, originally a Dutch settlement, which in 1790 is still resisting assimilation into the Anglocentric culture of the newly independent United States of America. The inhabitants seem to be quite consciously aware of the culture clash, too, and to regard it almost as an intellectual invasion when the town school committee hires a New Englander named Ichabod Crane (Will Rogers— yes, that Will Rogers) to take over the little one-room schoolhouse on the outskirts of the village. Once the school year gets underway, most of the griping about Crane will focus on his severe teaching style and frequent recourse to the ferule, but from the way a lot of the townies regard Crane even before he starts handing out regular thrashings to troublesome pupils like Adrian Van Ripper (Jerry Devine) and Jethro Martling (Sheridan Tansey), it seems clear that the main bone of contention is simply that he isn’t Dutch. Or at any rate, that’s the main bone of contention for most of Sleepy Hollow’s anti-Crane party. For Abraham Van Brunt (Ben Hendricks Jr.)— more commonly known as Brom Bones— the issue is more personal; the first thing Crane does upon arriving in town is to begin sniffing after Brom’s girlfriend, Katrina Van Tassel (Lois Meredith).

Understandably for a teacher, Ichabod Crane considers himself a learned man. In most areas, his opinion of his own intellectual attainment is rather highly exaggerated, but he really is something of an authority on the lore of ghosts and witchcraft (presumably due to having hitherto spent his life among descendants of the famously witch-obsessed Puritans). This makes Crane a big enough hit at social gatherings that some of the locals begin softening to him a bit, and a few are so charmed by his skill with a ghost yarn that they become willing to turn a blind eye to his relentless mooching. That conversance with the occult also gives Crane’s enemies some formidable weapons to use against him, however, for Crane accepts every one of the tales he retells as gospel truth, and New Englanders aren’t the only Americans who still believe in witches in 1790. Dame Martling (House of Mystery’s Mary Foy) and Hans Van Ripper (The Master Mystery’s Charles Graham)— the aggrieved parents of Crane’s schoolroom nemeses— soon get up a whispering campaign against the Yankee teacher, arguing that anyone who knows so much about witches, ghosts, and devils must be in league with them himself. Meanwhile, Brom Bones starts faking supernatural manifestations meant to frighten Crane out of town. The two conspiracies come together when Van Brunt pays Jethro Martling to pretend that Crane has put a hex on him; Ichabod is in the town pillory awaiting a tarring and feathering by the time Mayor Baltus Van Tassel (Bernard Reinold) and his friends on the school committee get wind of the mischief and put a stop to it. Brom Bones will have Crane out of Sleepy Hollow yet, however. After taking advantage of a party at the Van Tassel place to fill the teacher’s head with stories about the Headless Horseman— the most fearsome of Sleepy Hollow’s native ghosts and bogeymen— Van Brunt contrives to have his rival meet up with that legendary specter on his way home.

The natural assumption to make when confronted with a film adaptation of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is that it would be a horror movie. True, the term itself was not yet in use in the US as early as 1922, but movies had been giving Americans the shivers for a good fifteen years by that point, so the concept had surely been recognized in some form. If nothing else, 1922 audiences had The Avenging Conscience and the John Barrymore version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to serve as touchstones. And indeed, The Headless Horseman contains a remarkable early example of a technique that would remain part of the standard horror repertoire until the turn of the 1970’s— if the monster doesn’t show up until the final reel, then give the audience something to serve as a teaser during the first ten or twenty minutes. Ichabod Crane doesn’t sight the Headless Horseman until well past the hour mark (the widely reported 51-minute running time refers to the movie’s duration when played at talkie speed; at the correct frame rate, it runs about an hour and a quarter), but at the end of the first act, there’s a nicely spooky vignette introducing the idea that Sleepy Hollow is supposed to be haunted. A title card promises that Crane will soon have a run-in with the Headless Horseman (the “soon” part is a big, fat lie), and we cut to a graveyard in which a skeletal figure in a heavy cloak— looking much more phantasmic than the “real” Horseman we see at the end— mounts a horse and then gallops off into the woods. It’s essentially the same trick Bob Clark pulled 50 years later by beginning Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things with the world’s weirdest grave robbery, and it proves that director Edward Venturini understood that scare appeal was going to be this movie’s primary selling point. Hell, the change of title from The Legend of Sleepy Hollow to The Headless Horseman suggests as much all by itself.

But regardless of what was drawing in the customers, the horror in The Headless Horseman seems to be almost beside the point. The climactic chase and the aforementioned teaser are the only scare scenes in the movie, and neither one is integrated at all smoothly into its surroundings. Until the party at the Van Tassels’, we never so much as hear (okay, fine— read) one of those spook stories Crane is supposedly so adept at telling, and the only indication that there will ever be a Headless Horseman is the fact that this is a Sleepy Hollow movie, so there kind of has to be one at some point, right? Instead, the film bounces back and forth with no real momentum between the Ichabod Crane-Katrina Van Tassel-Brom Bones love triangle and the interloping teacher’s ongoing struggle against local prejudice. Worse still, neither aspect really works. Will Rogers was an odd casting choice for the dour and stuffy Crane, and he seems to be never quite sure whether he’s supposed to be playing the part straight or for comedic effect. The only recognizable joke in the film (and it’s rather funny, in a naďve way) doesn’t concern Crane at all, yet Rogers frequently conveys the impression that he’s waiting for the laughter of an audience that only he can hear to die down so that he can move on to the next bit. Crane is also just an incredibly unsympathetic character, and Rogers’s much-vaunted folksy charm does nothing to change that. His attraction to Katrina is depicted as having at least as much to do with Baltus Van Tassel’s money as it does with the girl herself, and he’s a short-tempered, self-impressed, and generally intolerable prig. One hates to side with bigots, but I’d want to run the fucker out of town, too, if he ever set up shop at my neighborhood elementary school. Of course, Brom Bones isn’t any better. This, after all, is a guy who’s willing to destroy someone else’s career and get them tarred and feathered in order to shore up his prospects with his girlfriend— who, while we’re at it, is a shamelessly manipulative cock-tease. And, heaven preserve us, these three are supposed to be the romantic interest of the film. It’s like “The Real World: Sleepy Hollow” or something! Though technically well made and of some historic importance (this was the first movie ever shot on panchromatic film, yielding a more natural, gradual range of grays between true black and true white than the old orthochromatic stock), The Headless Horseman is too thoroughly confused and mishandled to offer much more than antiquarian interest.

Thanks to Liz Kingsley for furnishing me with a copy of this film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact