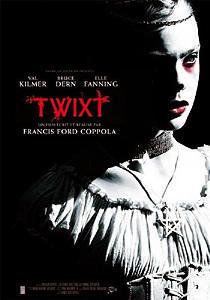

Twixt (2011/2012) ***

Twixt (2011/2012) ***

As Werner Herzog put it, even dwarfs started small. Oftentimes, though, people find that they miss that stage once they grow beyond it. The world is full of successful authors who embark on second careers under the cover of pseudonyms, popular musicians who quietly launch side projects, comedians who take a break from lucrative movie and television work to go back on the road doing standup. In the movie business, getting back to one’s roots ought to be relatively easy— just don’t demand so much money from your backers, and all the other hardships you’re nostalgic for should take care of themselves. I’m thinking of all this right now because Twixt is, among other, weirder things, part of Francis Ford Coppola’s recent ongoing project to get back in touch with the kid who made Dementia 13 and The Bellboy and the Playgirl. Like its predecessors, Youth Without Youth and Tetro, it’s small, intimate, and extremely quirky, and it leaves me hoping that it’ll take Coppola a while to work this longing for the freedom and simplicity of his Corman days out of his system.

A lot of people call Hall Baltimore (Val Kilmer, from Red Planet and The Island of Dr. Moreau) the bargain-basement Stephen King, but that might be giving him too much credit. After all, even if we disregard King’s substantial body of non-horror work, he still wrote about all kinds of stuff. Baltimore, on the other hand, writes about witches, witches, and more witches. Mind you, that isn’t the career he set out to have. It’s just that that first witch novel made a whole lot of money, and the next thing Hall knew, it was twenty years later, and he was in a rut so deep he could barely see out of it anymore. Meanwhile, his wife, Denise (Willow’s Joanne Whalley), is salivating over a new advance from his publisher, and threatening to sell his most prized possession if one is not forthcoming— even as his agent, Sam (David Paymer, of Drag Me to Hell and Night of the Creeps), refuses to countenance any such thing unless it’s part of a deal for yet another book about goddamned witches. Really, though, all you need do to understand the present state of Hall’s life and work is to take a good look at the current stop of the book-signing tour for his most recent novel. It’s bad enough that he has no entourage of any kind— not even a personal assistant or a secretary. But it’s practically an insult to his decades of toil that the tour is taking him to a shitty little nowhere town like Swann Valley, where the “book shop” consists of a few shelves tucked incongruously into the front window of the local hardware store!

In a way, though, coming to Swann Valley is a stroke of luck for Baltimore. His book-signing is a fiasco, of course, but he soon encounters something far more valuable than any mere gathering of fans— the raw material for a story that could get him out of the witch business once and for all. In fact, Hall finds so much raw material that he isn’t sure how to make use of it all. First off, the little hamlet is plagued just now by what Sheriff Bobby LaGrange (Bruce Dern, from Django Unchained and Swamp Devil) believes to be a serial killer. They’re weird murders, too; the most recent victim, an unidentified girl in her early teens, was found with a wooden stake pounded through her heart. The town also has an unsavory history, something about a horrible crime committed about 60 years ago by a pastor running an orphanage in a closed-down hotel where Edgar Allan Poe, of all people, once stayed for a while in 1843. Then there are the ongoing hostilities between the people of Swann Valley and the tribe of teenaged goths who live in an encampment on the far side of the river. Their leader, Flamingo (Alden Ehrenreich, of Beautiful Creatures), is LaGrange’s preferred suspect in the recent slayings, even if he has no actual evidence linking Flamingo or his followers to the crimes. And in a further interesting wrinkle, the goths’ campsite has apparently been inhabited by one band of outcasts or another since at least the 1950’s, when that mysterious bad business at the orphanage went down. Finally, Swann Valley just has an eerie atmosphere, due in large part to the historic clock tower, which not only has a wildly excessive seven faces, but is also incapable of keeping them all in synch. Disorienting as it is to be confronted with a different time for every 50 degrees one turns around the tower, the bedlam of inappropriate bell-ringing, 168 times per day, is even worse. Indeed, sometimes one clock’s chiming will bleed smoothly into another’s, so that the bells ring impossible hours like seventeen o’clock. Is it any wonder the local old-timers say the Devil hangs out in that belfry? When Hall realizes what an inspiringly peculiar place he’s stumbled into, he decides to blow off the rest of his tour and stick around to see if he can’t get some writing done.

It’s difficult to explain what happens next, beyond to say that Baltimore comes out of this unscheduled working holiday with a new book that satisfies both Sam’s desire for something commercial in the accustomed Hall Baltimore style and his own desire to prove that he can be more than just the Master of Witchcraft (as his publisher likes to call him advertisements and cover blurbs). Twixt is in large part an allegory of the creative process itself, and nothing should be taken at face value from the start of the first dream sequence twenty-some minutes in until the final scene of Hall handing over his manuscript for The Vampire Executions. The story repeats itself, retraces its steps, and changes its own terms with each reiteration, just as we may assume Baltimore revises the novel he’s working on throughout it all, rewriting sections and shifting the direction of the narrative as new ideas and new interpretations of old ones occur to him.

We can be more or less certain that we’re seeing the actual course of events when Baltimore visits the mad heptagonal belfry, the ruined Chickering Hotel, and the goth encampment over the river; when he combs the newspaper backfiles at the Swann Valley Public Library for information on the shadiest parts of the town’s history; and when he hangs around the sheriff’s office, chatting with LaGrange and his deputy, Arbus (Bruce A. Miroglio). Meanwhile, it’s possible that the sheriff really does try to foist himself on Hall as both a protagonist and a writing partner— however, that plot thread could just as easily be a metaphor for the author’s initial preconception that his new book is a straight detective story, since that’s what LaGrange keeps badgering him to write. There may also be some literal truth to the sequences in which Baltimore seems to discover evidence linking LaGrange to the murders he’s supposedly trying to solve, but since those scenes invariably contain material that pushes Twixt in a more fantastical direction, I wouldn’t bet too heavily on it. And as is only appropriate, the several lengthy dream sequences are an intractable tangle of the real and the imagined. Honestly, it isn’t even entirely clear to what extent they’re supposed to represent proper dreams, and to what extent they’re a shorthand for the almost trance-like state that comes over a writer who’s really on a roll. In any case, the dreams have Hall led about Swann Valley by spirit guides in the form of Edgar Allan Poe (Ben Chaplin, from Lost Souls and Dorian Gray) and a twelve-year-old girl named Virginia (Super 8’s Elle Fanning), whom Hall associates with both the impaled girl in LaGrange’s morgue and the sole survivor of the 1955 orphanage massacre. These figures mostly show Baltimore imperfectly reconcilable versions of the events he investigates at the library, but they also force him to face his long-suppressed feelings of inadequacy and guilt over the death of his daughter, Vicky (Fiona Medaris), in a boating accident some years back. The upshot of it all is, Twixt keeps you on your toes. One minute, you seem to be watching a present-day thriller about a serial killer, and the next, it’s a period piece about an evil religious fanatic. Then it’s a dark counterculture melodrama about a bunch of troubled kids under attack by a small-minded small-town sheriff. And just when you’ve settled into that groove comfortably enough— *BOOM!* Edgar Allan Poe’s doomed child bride is a fucking vampire. Yet somehow or other, it’s all the same story.

Oh— and the original plan was for Twixt to be even stranger than all that. One of the factors driving Coppola’s return to filmmaking on a smaller scale was the advent of digital video, which drastically shrank the overhead associated with producing a movie by eliminating the traditional expense of lab costs, allowing a much larger proportion of a little budget to make its way onto the screen. For somebody with a well-known name to trade on, digital video could even promise liberation from the usual studio bullshit, since the combination of fame and modest startup cost ought to make outside-the-system financing relatively easy to secure. That was a very attractive prospect for Coppola after the bloated, aggressively managed work-for-hire projects that had essentially chased him into semi-retirement in the late 1990’s. Digital video also looked attractive on creative grounds. For starters, it opened up a lot of new scope for color and lighting effects; with the technology behind That Damned Blue Filter in their hands, an imaginative filmmaker could do things that Mario Bava only dreamed about. The most radical possibility of all, though, lay in the field of editing. Digital video files can be cut and recut at will, limited only by the nimbleness of the editing software. In theory, a person with a good laptop full of video clips could mix them on the fly like a dance-club DJ matching playlists to the mood of a crowd. That was the capability Twixt was designed to exploit. It was Coppola’s plan to roadshow the movie in person, editing it live at every screening so that no two audiences would ever see exactly the same film. He would become just as much a performer as Val Kilmer or Bruce Dern, and Twixt would take on whatever pace or tone a given set of viewers desired of it as scenes were trimmed, stretched, dropped, added, reordered, or replaced with alternate takes. I’m honestly not sure whether any of that actually happened, however. Coppola certainly gave a demonstration of his live editing technique at the San Diego Comic-Con in 2011, but Twixt’s early festival screenings appear to have been conventional static presentations (although they may have used a different cut than the one that hit home video a year later), and I’ve seen little sign that the movie ever had a regular theatrical run, roadshow or otherwise. It may be that Coppola was unable to make the system work the way he wanted, or that he failed to line up exhibitor support for such an unorthodox project. In any case, there was obviously no prospect of the gimmick surviving once Twixt went to DVD, streaming video, and the like. The version of Twixt you’ll see today is just another movie, bearing no trace of its creator’s slightly mad notion beyond the aforementioned recursiveness of the plot.

Reaction to Twixt has been mixed to say the least, but in a reasonably orderly and dependable way. The art house crowd seems to have been favorably disposed, while those who seek to relate to it as a horror, mystery, or suspense picture are having none of it. Unusually, I’m with the artsy types this time around. I wasn’t sure what to make of Twixt initially, but once I caught on to Coppola’s game, I decided that I liked it quite a bit. It plays more like a David Lynch movie than like anything else of Coppola’s that I’ve seen, which is to say not only that Twixt practically dares you to make sense of it, but also that there’s a definite purpose behind its stylistic excess and overall screwiness. This is no Bram Stoker’s Dracula, in which the intensive manipulation of imagery serves only as a mask for triteness, superficiality, and ineptitude, or in which the repeated shifts in tone are merely the result of insufficiently focused characterization. You just have to dig a little to discover the underlying patterns here, in very much the way Lynch fans know so well. Twixt is also a surprisingly funny movie, especially when it deals with the frustrations that go along with creating commercial art: public disdain and incomprehension, the pressure toward hackwork, the tendency of the Muse to be out of the office exactly when her assistance would be most appreciated. Perhaps most enjoyably of all, Twixt provides a showcase for two over-the-hill performers to demonstrate range that they never made much use of in their respective heydays. I’ve long been of the opinion that Grizzled Old Character Actor Bruce Dern is far more interesting than Face of the Counterculture Bruce Dern, but Doughy Sadsack Character Actor Val Kilmer is new to me. It turns out he possesses a level of charm, wit, and personality that was rarely even hinted at by Sexy Superstar Val Kilmer in the 80’s and 90’s. That too is something I’m looking forward to seeing more of, just as I’m looking forward to seeing more of Weirdo Low-Budget Visionary Francis Ford Coppola.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact