Son of Samson / Maciste in the Valley of the Kings / Maciste the Mighty / Maciste nella Valle dei Re (1960/1962) **½

Son of Samson / Maciste in the Valley of the Kings / Maciste the Mighty / Maciste nella Valle dei Re (1960/1962) **½

Once Hercules Unchained proved that the colossal international success of Hercules was no mere fluke, it was only to be expected that Italian filmmakers would descend upon the resurgent peplum genre like the eighth plague of the Pharaohs. Among the first locusts to alight were a pair of producers named Piero and Ermanno Donati, who had played a similarly pioneering role in the revival of Italian horror with The Devil’s Commandment a few years before. But unlike the makers of other early-bird neo-peplums like The White Warrior and Goliath and the Barbarians, who sought to cash in by exploiting the unlikely star power of Steve Reeves, the Donatis and their partner, Luigi Carpentieri, tried to create a new star by importing their own retired American bodybuilder. They also took a canny gamble with their choice of heroes for the new guy to play. Instead of commissioning a script about some other Greco-Roman demigod, who would just have been overshadowed by Hercules anyway, Carpentieri and the Donatis resurrected Maciste, the strongman hero played by Bartolomeo Pagano in literally dozens of silent-era adventure movies, starting with Cabiria. Audiences outside of Italy might find that decision baffling (non-Italian distributors certainly did, as we’ll discuss shortly), but Maciste was a big damn deal in his country of origin. Benito Mussolini himself had tried to capitalize on the character’s popularity by modeling his own propaganda photos after Pagano’s publicity headshots. (Mussolini flattered himself by imagining that he actually resembled Pagano— and I guess he sort of did, if we stipulate the paunchy, bald, middle-aged Paganno of the 1920’s.) The bid paid off handsomely, and although Maciste in the Valley of the Kings was by no means a hit on the same scale as Hercules, it did well enough to initiate a whole new cycle of Maciste pictures, ultimately rivaling the output of the original series.

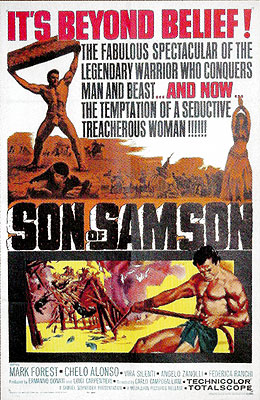

Everywhere else, however, Maciste was, if anything, even less well known in 1960 than he is today. It would have taken a bold distributor indeed to offer him up as a competitor to Hercules in the United States, for example, where most cinemagoers would have found it difficult even to pronounce the character’s name. (For the record, it’s either “mah-CHEES-tay” or “mah-CHEEST,” depending on whether you prefer an Italian dialect that sounds or drops its terminal E’s.) Consequently, virtually all of the 1960’s Maciste movies that played in American theaters, or aired on American television, resorted to some kind of workaround, if only in their titles. Some distributors rechristened the hero “Colossus,” “Samson,” “Atlas,” or “Goliath.” Others, operating at the intersection of laziness and shamelessness, just called him “Hercules”— a name which, after all, was in the public domain, however inconvenient that might have been for Joseph Levine. But the most popular single solution to America’s Maciste problem was to pass off the hero as the son of somebody more recognizable. Usually that meant billing Maciste as the son of Hercules (who else, right?), especially after Embassy Pictures bundled together thirteen previously un-imported peplum flicks to create a “Sons of Hercules” package for television syndication. Medallion Pictures took a different tack, however, when they brought over Maciste in the Valley of the Kings in 1962. Cashing in on a different blockbuster epic about a boulder-tossing strongman, they glossed Maciste as the Son of Samson.

You should pretty much disregard the historically illiterate opening narration of the US version. If Egypt is having problems with Persian cavalry raids, then this isn’t the 11th century BC, but the 6th. Also, screenwriters Oreste Biancoli and Ennio de Cocini seem to have skipped a pharaoh, since “Armiteo” sounds to me like an Italianate garbling of Ammis, whereas the pharaoh who was conquered and ultimately executed by Shah Cambyses was Psamtik III. How much historical accuracy can we expect, though, from an old sword-and-sandal flick, right? Besides, Son of Samson is about to posit that the Egyptians disapproved of slavery, which is easily the most fantastical thing about this movie. Anyway, after a squadron of Persian horsemen sack a village, slaughter the menfolk, and march the women off into slavery, a few survivors who escaped the destruction come to petition the pharaoh (Carlo Tamberlani, from The Colossus of Rhodes and The Minotaur: The Wild Beast of Crete) for justice. That makes some sense because they and the survivors of similar raids have discovered evidence that the Persians’ depredations are being knowingly permitted and even encouraged by Armiteo’s youthful wife, Queen Smedes (Chelo Alonso, of Sheba and the Gladiator and The Huns), and chief advisor (Zvonimir Rogoz). Armiteo is just about to have both traitors put to death when one of the queen’s agents snipes him from outside a throne room window with a recurve bow. (Incidentally, the property master who devised the weapons in this movie clearly didn’t understand how recurve bows work.) Mind you, the assassination doesn’t technically put Smedes in command; under Egyptian law, Armiteo’s son, Kenamun (Angelo Zanolli, from Uncle Was a Vampire and Hercules Unchained), is next in line for the throne. However, Kenamun is young and inexperienced, and more importantly, he’s currently far away from the palace. Smedes and the crooked counselor figure they’ll have little trouble controlling him, and they’ll have plenty of time to bullshit up a less damning explanation for his father’s death before they have to deal with him face to face.

So where is Kenamun if not at the palace? Why, he’s out in the countryside, fighting Persians, of course. Wounded in action, the prince is nursed back to health by a peasant girl named Nofret (Federica Ranchi, from Vengeance of Hercules and Women of Devil’s Island), with whom he swiftly falls in love. Nofret’s village has been too thoroughly plundered for anyone to stay in it any longer, however, least of all the crown prince of Egypt, and so Kenamun sets off as soon as he is able for Tanis, his father’s capital. Meanwhile Nofret and her fellow refugees caravan away in search of a new home. The two parties’ fortunes on the road are at once drastically different, and yet not so different at all. You see, Kenamun has a chance meeting with Maciste, the legendary son of Samson (Mark Forest, of Kindar the Invulnerable and Hercules Against the Sons of the Sun), during which the two men end up saving each other from a pair of lions. Although that would seem to mean their debts to each other are repaid as soon as they’re incurred, neither Kenamun nor Maciste sees it that way, and they part with a vow of mutual aid and friendship. Nofret and her people, on the other hand, fall into the hands of Persian slavers. They don’t stay in bondage very long, however, because they and their captors soon cross paths with Maciste as well. The son of Samson mops the floor with 40 armed and mounted soldiers (albeit using a millstone instead of the jawbone of an ass), and then somewhat reluctantly accepts guardianship over the refugees until they can reach safety in Memphis. While shepherding them thence, Maciste catches the eye of Nofret’s friend, Tekaet (Vira Silenti, from Atlas Against the Cyclops and The Witch’s Curse), of whom he grows rather fond himself.

As you would expect, Kenamun’s arrival in Tanis plunges him headfirst into all manner of skullduggery directed against him. Smedes informs him that the conquering Persians expect him to marry her— their willing agent in Egypt— in his father’s place now that the old pharaoh is dead, and nevermind any low-born floozies he might be sweet on as a result of his sojourn among the rabble. When Kenamun refuses, he discovers that he is a virtual prisoner in his own pharonic palace. Worse yet, Smedes and the counselor have a plan for bending the prince absolutely to their (and thus the Persians’) will. Among the nifty toys possessed by the priesthood is a little item called the Necklace of Forgetfulness, which Smedes contrives to give Kenamun as a coronation present. So long as he wears it, he won’t remember a thing about Nofret, Maciste, or his vow before his father’s sarcophagus to liberate Egypt from the Persian yoke.

Meanwhile, Maciste and the refugees fall in with a traveling merchant called Senneka (Nino Musco, from Smell of Flesh and Secret Confessions in a Cloistered Convent). On the one hand, this guy is kind of a prick, and would probably sell his own grandmother if the price were right. On the other hand, he’s absolutely no friend of the Persians’; after all, war is bad for business in a pre-capitalist society. Beyond that, Senneka knows lots of tricks for staying out of trouble, which is a talent that Maciste and his wards will soon be needing. You see, once Maciste meets Nofret, he rather naively gets it into his head that all the country’s problems could be solved if he just brought everybody to Tanis, and let them tell Kenamun what it’s like out there in the real world. Obviously, Smedes isn’t going to like that idea, especially if Maciste manages to find a way around the Necklace of Forgetfulness. And this is a gal with her own personal crocodile pool we’re talking about.

Before we get too deep into discussing the merits and faults of Son of Samson, there’s an easily missed minor point to which I’d like to draw your attention. In Cabiria, Maciste was explicitly identified as a Nubian, and Bartolomeo Pagano played him wearing blackface. At some point between 1914 and 1960, however, that detail fell by the wayside. Neither Mark Forest nor any of his many successor Macistes were ever made to look any darker than they could have become just from parading around shirtless in the bright Mediterranean sun, thank Jupiter. But by the same token, no black actor has ever played the character, either, to the best of my knowledge, and that strikes me as a serious oversight. If anyone in Hollywood is taking requests, tell ’em El Santo wants a movie where Winston Duke plays Maciste. Maybe he can team up with the Rock’s Hercules, and go fight some actual fucking monsters this time.

One way to look at the peplum revival of the 50’s and 60’s is to separate it into two parallel strands, the historical and the fantastical. On one side, you’d have all the more or less realistic movies about gladiators, legionnaires, steppe nomads, and Vikings, with their obvious ties to both the Imperial Roman epics of Italy’s silent era and the swashbuckling adventure movies of Hollywood’s big-studio golden age. And on the other, you’d have Hercules and its progeny, the films in which mythical heroes fight monsters and consort with gods, set in an age best thought of as Terry Gilliam’s Time of Legends. Son of Samson, curiously, belongs to both strands at once. For all the impossibility of reconciling its story with actual past events, the fact remains that it invokes real places and real cultures, along with a recognizable (if much distorted) interpretation of real relationships between them. Persia did, after all, conquer Egypt, with Memphis falling to the armies of Cambyses in 525 BC. And although contemporary Egyptian sources don’t well support a narrative of the Nile valley groaning under Persian tyranny, later Hebrew sources do (for complicated reasons having little to do with Egypt, and much to do with cultural considerations internal to ancient Israel). And then into that picture strides the superhuman, supernatural, and flagrantly ahistorical figure of Maciste. It’s very strange, and compelling enough that I can understand Italian audiences wanting to see it 24 more times. (Well, okay— maybe not 24 more times…)

Mark Forest cuts a curious figure in the title role. Although he can’t match Steve Reeves’s physical perfection or Bartolomeo Pagano’s natural flamboyance, he projects a clunky, impassive solemnity that rather befits a hero who at one point translates his name to mean “Born from the Rocks.” (Actually, the name comes from a town in the Peloponnese, where there used to be a temple to Hercules in Roman times, but that’s a bit beside the point right now.) Forest’s performance also synchs up rather nicely with the theme of destiny that runs through Son of Samson. Maciste in this movie is not a self-motivated hero. He has no back-story to explain his wandering one-man war against oppression, nor does he ever speak of having a cause or a commission. Rather, when he initially resists the idea of accompanying Nofret and her people after rescuing them from captivity, he phrases his objection in terms of being called as if by forces outside his will to save others elsewhere— but not specific others, in any specific place. It’s simply that saving people is what Maciste is fated (and perhaps was created) to do. A guy whose idea of acting is just to stand uncomplainingly where the director tells him to stand, and to say uncomplainingly what the script requires him to say, isn’t such a bad choice for a part like that, even if he’s constantly being eclipsed from the viewer’s attention by more forceful performers like Chelo Alonso and Nino Musco.

A much more serious defect in Son of Samson is the lack of connective tissue surrounding the action set-pieces that ensue upon Maciste’s arrival in Tanis. A lot of stuff happens, and most of it is pretty impressive to watch (I especially like the scene in which Maciste protects a gang of laborers from being crushed under the obelisk they were working to erect by holding it up singlehanded until someone can replace the ropes that failed), but most of the events could be shuffled into almost any other order without seriously altering the shape of the story. Furthermore, the few bits that do need to be in the order in which they’re actually presented form a subplot that really shouldn’t be here at all. You see, Maciste’s efforts to reconnect with Kenamun quickly bring him into contact with Smedes instead, upon which the queen does her level best to seduce and thereby neutralize him. This subplot is plainly modeled on Samson and Delilah (indeed, I wouldn’t be surprised if its presence here partly explains why Medallion gave this movie the title they did), which is a completely different kind of story from the one Son of Samson is telling. Samson and Delilah is a tale of hubris and fucking up, followed by redemption at immense personal cost; Maciste, in contrast to Victor Mature’s interpretation of his putative father, is neither sufficiently flawed nor sufficiently self-willed for any of that. And in fact the movie is forced to contrive all sorts of “just ’cause” non-reasons for Maciste to cooperate with what he definitely realizes is a trap, and for Egypt’s downtrodden to suspect him of betrayal while he does nothing but what he told them he was planning to do in the first place.

All that said, Son of Samson is fairly enjoyable as an exercise in pure spectacle. Chad “3 Beer Man” Plambeck, who used to write 3-B Theater and Micro-Brewed Reviews, and who now devotes his film-crit efforts to the Atomic Weight of Cheese podcast, once told me that he divides peplum movies into the ones that can afford horses, and the ones that can’t. Son of Samson doesn’t just have horses— it has stunt horses, and a fair many of them at that. Hell, it even has a chariot race, although nobody’s ever going to mistake it for any version of Ben Hur. The major battle scenes convey the appropriate senses of scope and scale, and the one near the end, between Maciste’s rebels and the Persian-controlled Egyptian army, is remarkably harsh and bloody for 1960. Mark Forest performs a few genuine feats of strength that make him look very much like a real-life superhero, along with some bits of lion- and gator-wrestling that appear to be not entirely faked. Chelo Alonso’s Dance of the One Big Veil during the seduction subplot is sexy as hell, even if other Italian genre movies would raise the ante on it considerably during the next few years. And of course nothing in the world adds production value to a movie set in Egypt like second-unit footage shot in the shadows of real ancient ruins. More than anything, the sword-and-sandal pictures of the 50’s and 60’s were meant to give audiences something to “ooh” and “ah” over, and Son of Samson amply satisfies that requirement.

Can you believe the B-Masters Cabal turns 20 this year? I sure don't think any of us can! Given the sheer unlikelihood of this event, we've decided to commemorate it with an entire year's worth of review roundtables— four in all. These are going to be a little different from our usual roundtables, however, because the thing we'll be celebrating is us. That is, we'll each be concentrating on the kind of coverage that's kept all of you coming back to our respective sites for all this time. For our final 20th-anniversary roundtable, to which this review belongs, we're looking forward instead of back, to write up some movies of types that we intend to cover more frequently in the years to come. Click the banner below to peruse the Cabal's combined offerings:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact