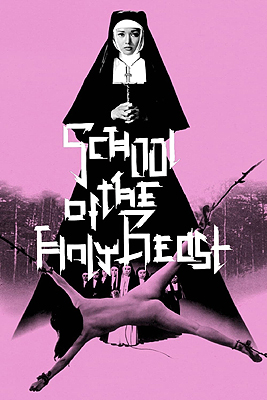

School of the Holy Beast / Convent of the Sacred Beast / The Transgressor / Seiju Gakuen (1974) ***

School of the Holy Beast / Convent of the Sacred Beast / The Transgressor / Seiju Gakuen (1974) ***

My operative theory of nunsploitation has always been that it requires a Roman Catholic culture to take root. After all, the soul of the genre is the frisson of scandal that comes from imputing every sin in the book to people and institutions meant to embody purity and holiness. For that to work, surely one has to start with the assumption that nuns and convents do or at least should embody those things, right? And for the most part, the facts on the ground seem to bear that theory out. Nobody got deeper into nunsploitation than the Italians, and what competition they had came mainly from France, Spain, and Mexico. Protestant Europe largely directed the same impulses into the witch-burner genre instead, while the United States, having no formally established state church to take potshots at, went all-in on movies about cults, whether fundamentalist Christian, Satanic, or somehow both at once. So what in all nine of the Hells are we to make of School of the Holy Beast, a Japanese nunsploitation movie in a style barely distinguishable from that of Catholic Europe? There aren’t but 430,000 Catholics in all of Japan, representing about a third of a percent of the total population! I could maybe see that country developing its own parallel nunsploitation tradition revolving around nuns of the Buddhist persuasion, but what could possibly have provoked co-writer/director Norifumi Suzuki (or the makers of Wet Rope Confession, The Sins of Sister Lucia, Cloistered Nun: Runa’s Confession, and so on) to do something like this?

The closest I can come to answering that question, even conjecturally, is to point once again to the tendency in Japanese pop culture to treat Christianity as an occult phenomenon. Maybe Japanese nunsploitation scratched an altogether different set of itches from the Occidental strain, however similar the movies themselves might have been. Perhaps domestic audiences experienced School of the Holy Beast and its ilk not as subversive brickbats hurled at a corrupt establishment, but rather as something akin to Virgin Witch or The Witchmaker, in which the attraction is the luridly immoral behavior of disreputable weirdoes. In any case, there is one important respect in which School of the Holy Beast specifically differs from most of its Western counterparts. Whereas European nunsploitation flicks tend to be as grotty in execution as they are in subject matter, Suzuki brought to this one an altogether unexpected degree of visual artistry— without sacrificing one iota of shock value or perversion! School of the Holy Beast may be as slimy and reprobate as anything that ever slithered out of the vaults at Eurocine, but it was produced by Toei, and displays the full fit and finish of a major film company’s mainstream output.

Seventeen-year-old Maya Takigawa (Yumi Takigawa, from Virus and Champion of Death, in her acting debut) never met either of her parents, and indeed doesn’t even know who her father was. She does know, however, that her mother, Michiko Shinohara (played in flashbacks by Kyoko Negishi, of Ranking Boss Rock) had been, of all things, a Roman Catholic nun at the Convent of St. Clore. Obviously there has to be a story there, and as her eighteenth birthday— December 25th— approaches, Maya settles upon a plan to discover at last what that story is. After squeezing every form of pleasure she can think of— a pro hockey game, a carnival, a motorcycle ride, some barhopping, a nice dinner out, and of course a night of wild sex with a total stranger by the name of Kenta (Hayato Tani, from Delinquent Girl Boss: Blossoming Night Dreams)— into about 36 hours, Maya enrolls at the very convent where her mother took her vows.

Naturally Maya doesn’t get so lucky as to meet her mom behind the walls of St. Clore’s. Nor does it take her long at all to suss out the convent as a bottomless pit of sadism, perversion, and hypocrisy. For instance, one has to look askance at any institution that claims to place such emphasis on the denial and renunciation of sexuality while also having its inductees perform their initiation rites in the nude. Similarly, I’d hesitate to describe the ecstasy with which one of the other novices flogs herself in the dormitory during Takigawa’s first night at the convent as religious. Sadako Matsumara the abbess (Yoko Mihara, of The Erotomaniac Daimyo and The Lady Vampire) and the other senior nuns all take visible pleasure in devising baroque forms of corporal punishment to inflict on their fellows who violate any of the 73 chapters of St. Clore’s code of conduct, like when they catch two novices sneaking food, and force them into a topless whip-fight in the convent’s “persecution room.” On a less titillating, but equally corrupt note, novices whose families didn’t pony up with big donations upon their induction are treated markedly worse than their sisters with big-spending relatives, facing heavier chores, shorter rations, and altogether stiffer discipline. And the novices themselves are hardly models of demure comportment, either. What with the lesbianism, the petty larceny, the secret stashes of pornography, the contraband lingerie, and the snitching on all of the above to curry favor with their superiors, it’s hard to tell the difference between the Convent of St. Clore and a reform school. In fact, one of Maya’s fellow initiates, a brassy girl by the name of Matsuko Ishida (Emiko Yamauchi, from Neon Jellyfish and Curse of the Dog God), was for all practical purposes sent to the convent in lieu of juvie hall.

Matsuko believes that Maya is the reason why the higher-ranking nuns have been so much better informed of late about the initiates’ transgressions, and it’s certainly true that Takigawa has been doing a lot of snooping since she arrived. But as Maya herself has discovered, the real spy is a gaijin novice named Janet (Marie Antoinette, if you can believe that), who’s been telling on her sisters in order to cover up the lesbian affair that she’s been having with one of the less harridanish members of the choir. Catching the two of them together gives Maya her first opening for serious detective work, because she’s able to leverage her knowledge of the affair into a chance to look through the convent’s records. In the abbess’s files, Maya discovers a personnel ledger recording her mother’s death, supposedly of a heart attack, together with a note stating that the event was witnessed by Aya Ogasahara (Akiko Mori, from Tokyo Deep Throat and Female Prisoner Scorpion: #701’s Grudge Song), evidently the convent’s head cook. Aya is still around, although she’s now gravely ill, and might not live much longer. Maya goes to see her in the infirmary, and comes away with the impression that the old lady knows quite a bit more than she’s willing to tell.

Meanwhile, St. Clore’s is rocked by a fresh scandal thanks to one of the few genuinely devout novices, Hisako Kitano (Yayoi Watanabe, of Karate Warriors and Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope). Upon learning that her family needed ¥100,000 to pay her father’s hospital bills, she stole half that much from the office of the vice-abbess (Kimura Yumi, I think). Matsuko manages to embarrass the vice-abbess into abandoning her hunt for the culprit by volunteering to be strip-searched, but the crime remains on everyone’s mind when Father Kakinuma (Fumio Watanabe, from The Street Fighter and Shogun’s Joy of Torture), the priest under whose authority the convent falls, drops in for an official visit. Hisako’s guilty conscience prompts her to confess to Kakinuma what she would not confess to the senior nuns, and although the priest offers her his own personal absolution (together with the other ¥50,000 for her dad!), he terrifies her a moment later by asserting that God does not forgive her, just as He does not, has not, and never will forgive anyone for anything! Then, as if to emphasize just how little Hisako can depend on divine protection, Kakinuma rapes her. Hisako becomes pregnant with the priest’s child, and you’d best believe there’ll be all new kinds of hell to pay once that comes out.

The vice-abbess may have found neither the thief nor the missing money, but she did stumble upon one young nun’s collection of dirty pictures while tossing the novices’ dormitory. She confiscated the photos, of course, but she’s been unable to make good her intent to destroy them. Instead, she hides the pictures in her own desk, where the temptation they represent quickly overpowers her religious convictions. Even the novices notice the vice-abbess’s unbridled horniness, until Maya commits her most drastic transgression yet. Slipping out of the convent late one night, she changes back into street clothes, seeks out Kenta and his dorky friend, Tatsuhei (Hichiro Tako, of Sex Horoscope: Live Tasting), and then sneaks them into St. Clore’s disguised as nuns to give the vice-abbess what she has so obviously been craving! Kenta and Tatsuhei make a clean getaway just before dawn, but Maya is caught helping them scale the outer wall. It’s like a scene from a Jim Wynorski sex comedy got spliced in by mistake!

School of the Holy Beast reverts to its old self with a vengeance after Takigawa’s capture, with a torture scene that I won’t soon forget. Surprisingly, it’s Matsuko who rescues Maya from the Thirteenth Punishment, in the girl-gangster fashion she employs whenever she wants to make absolutely certain the senior nuns understand that they’ve lost a round. That’s the last such intervention that Takigawa will enjoy, however, for it results in her fierce rival’s immediate expulsion. And perhaps more ominously, Maya dropped her mother’s engraved crucifix during her travails, and the abbess picked it up. Mother Matsumara has ample reason to recognize that cross, because Michiko Shinohara had been her nemesis all throughout the latter nun’s career. During their novitiate together, Michiko had been the Gallant to Sadako’s Goofus, and Shinohara continued winning accolades that Matsumara sought until just about nine months before her death. Indeed, Michiko had even been the preferred candidate to become the abbess of St. Clore’s once! But the women’s rivalry had a more personal dimension as well. Sadako was in love with Father Kakinuma, and hoped to become his mistress after she willingly surrendered to his appetite for nun-fucking. Evidently Michiko was better at that too, however— but since she, like Hisako, got knocked up by the priest, the affair eventually presented Matsumara with an opportunity to be rid of her adversary once and for all. Obviously it wouldn’t do for a pregnant nun to become abbess, and once Sadako had the position in the bag, she used her new authority to settle a lifetime’s worth of accounts. Michiko was imprisoned and subjected to every form of torture that her enemy could devise, until finally she hanged herself at midnight going into Christmas Day. She went into labor as she strangled, and by the time her body was found by Aya Ogasahara, the baby that would grow up to be Maya Takigawa was born; Ogasahara spirited her away to an orphanage for safe keeping. Maya hears that story from old Aya as a deathbed confession just as Mother Matsumara is explaining the implications of her annoying new novice’s crucifix to Kakinuma. Each nun comes away with the determination to make things very hot indeed for the other, but Matsumara can’t quite bring herself to obey Kakinuma’s command to offer Maya up in human sacrifice. When the abbess fails to give Kakinuma what he wants, the priest summons from France an inquisitor nun by the name of Natalie Green (Ryoko Ema, from Girl Boss Guerilla and Confessions of Lady Mantis). Western viewers might need help grasping the symbolism, but the home audience would have understood what bad news Sister Green was the moment they saw her unique habit of pure and spotless white— the color of death in Japanese culture.

Another important point that Westerners might miss on their own concerns the origin story of Father Kakinuma, who lost his faith in divine benevolence— but not divine punishment— during the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Nagasaki isn’t just a port city, you see. It was the port city where Portuguese traders first established themselves in the 16th century, and it remains to this day the capital of Japanese Roman Catholicism as a consequence. And as with Hiroshima, the biggest reason why it wound up on the list of potential targets for nuclear attack in the summer of 1945 was because it had somehow gone all those months since the preceding spring without being bombed flat by conventional means. For those inclined to read messages of divine judgment into events in the material world, it must indeed have been a faith-testing situation when God’s own city, having been largely spared the apocalyptic destruction visited on most of Japan’s large population centers throughout 1944 and 1945, fell victim to an even more horrid annihilation in literally the final days of the war.

That background informs Kakinuma’s behavior and character arc (Maya’s character arc, too, for that matter) in surprising but psychologically astute ways, and undergirds the idiosyncratic theology implied by School of the Holy Beast’s denouement. You see, it isn’t just post-traumatic nihilism driving Kakinuma’s depravity, but a cockeyed quest for reconciliation with the divine. He emerged from beneath the mushroom cloud with his belief in God intact, but his understanding of Him forever altered. If God does not succor or protect the faithful (and He certainly didn’t that day in Nagasaki), but merely rains punishment upon the guilty, then it follows that sin itself is the only way to get God’s attention. Kakinuma thus fornicates, rapes, tortures, and murders for essentially the same reason that a neglected teenager might shoplift, hook school, and date dirtbag boys whom her parents can’t stand. And in the person of Maya Takigawa— born, let us not forget, in the pre-dawn hours of Christmas morning— God at last sends Kakinuma the retribution he’s been courting and craving for almost 30 years. From the perspective of a Christian culture, the positioning of Maya as a second Christ with an exceedingly narrow and vindictive new mission reads as a startlingly bizarre blasphemy. But if we reconceptualize Yahweh as one of the much smaller gods of Shinto, the Incarnation might indeed logically lose its unique and ostensibly universal import to become merely the power that God invokes when he’s really serious about getting something done. Strangely enough, then, School of the Holy Beast gives God a much bigger, more active, and more overt role than He plays in any Western nunsploitation movie of my acquaintance!

I guess it stands to reason that anyone who’d take the trouble of devising a coherent syncretic theology for a naughty nun flick would go the extra mile in other ways, too, and Norifumi Suzuki most assuredly does. In Japanese terms, School of the Holy Beast belongs to the metagenre of ero-guro— the erotic grotesque. Suzuki had more resources at his disposal, however, than did the makers of the last ero-guro movie we looked at, Entrails of a Virgin. He took full advantage of everything Toei had to offer, from the studio’s recruitment program for young starlets to the trained and well-supported professionals of its technical departments to achieve a seamless melding of the horrible and the beautiful. Nowhere is this displayed to better effect than in the torture scene that follows the film’s brief detour through sex-farce territory. Kneeling on the floor of the Persecution Room and stripped to the waist, Maya is bound about her whole upper body with coils of green bramble, which two of the elder nuns pull ever tighter from either side so that the thorns dig deeper and deeper into her naked flesh. And when it becomes obvious that Takigawa will never confess to or repent of her role in the infiltration of St. Clore’s by randy males, the nuns of the choir all surround her to pummel her with bouquets of long-stem roses— the dislodged petals of which mingle with Maya’s blood in a squall of raining red. The whole sequence is breathtaking, in the inventiveness of its sadism, in the painterly meticulousness of its composition, and most of all in the effortless fluency with which the two are combined. Flavia the Heretic and The Sinful Nuns of St. Valentine, try as they might, have nothing to equal it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact