Roar (1981) ?!?!?!

Roar (1981) ?!?!?!

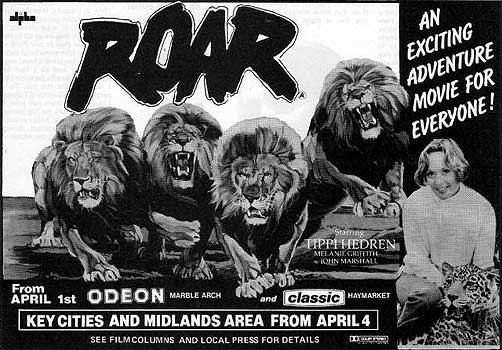

This is a story of Hollywood do-gooding gone awesomely awry. At the turn of the 70’s, actress Tippi Hedren went on safari in Mozambique with her then husband, producer and talent agent Noel Marshall. The experience sensitized both of them to the precarious position of Africa’s wildlife, threatened by overhunting and habitat loss. The big cats had it especially bad, thanks to our species’ longstanding and superficially quite rational intolerance for predators capable of menacing us or our livestock. The couple also brought home with them a memory of riveting visual power: a former plantation house turned game warden’s residence, rendered uninhabitable by flood damage and now taken over by a huge pride of lions. Marshall and Hedren decided to make a film together in the hope of raising the public’s environmental consciousness just as theirs had been raised, and to build that film somehow around the image of that lion-occupied villa in Mozambique.

The plan hit a snag very quickly, however. The scenario that Marshall and Hedren had in mind called not for two or three lions, but for two or three dozen. Every trainer they talked to told them that was never going to work. Lions are intensely territorial, and the only way they’ll tolerate each other’s presence in such numbers without a fight is if they’ve been raised together from cub-hood, as prides are in the wild. The couple’s response to this news was breathtaking in its mixture of surface-level practicality and profound clueless arrogance. They began acquiring lion cubs with an eye toward bringing them up as siblings to create their own synthetic pride. Let me stress that they did this at their house. In Beverly Hills. Where they lived with their four children. Truly there is no end to the shit you can get away with when you’re rich and famous. When the supply of existing cubs proved inadequate to their purposes, Marshall and Hedren bought an adult male and his harem of lionesses from— and you’re never going to believe this— International Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey. That enabled them to launch a breeding program, and to do so without waiting for any of their own cubs to reach maturity. Next, the Marshalls learned that adult lions can assimilate into an existing pride if they’re introduced one by one. It just requires a bit of sparring for the newcomer to establish its place in the dominance hierarchy. That realization coincided more or less with the Marshalls becoming exercised over the rampant mistreatment of big cats in the entertainment industry, with the result that they started taking on not just adult lions, but also tigers, leopards, jaguars, cheetahs, pumas, servals, and who knows what else. Eventually, these ultimate cat hoarders were forced to acknowledge at least so much reality as to drive them out of their mansion and into a ranch further out in the exurbs, where the proliferating animals could be kept under slightly less ridiculous conditions.

The ranch also afforded the opportunity to begin construction on a replica of the house in Mozambique, to become the main set for the film that this extraordinary breeding and rescue project was launched to support. By the time the faux-African villa was complete, the family had around 150 big cats of all species, to say nothing of a flock of flamingos and an elephant or two. Marshall, Hedren, and the kids continued to live among this lethal menagerie as if it were so many Siameses and Maine coons, for if the object was to show the world that humans and the great cats could coexist, then what better proof than their own lifestyle? It was rug-chewing, pants-on-head crazy, of course, as circumstance amply demonstrated once the family got to work for real on their movie. As the tagline on the Alamo Drafthouse-Olive Films Blu-Ray disc puts it, “No animals were harmed during the making of this film. 70 cast and crew members were.” And actually, even that understates the case, because it counts only the injuries documented by hospitalization. Marshall’s eldest son, John, turned out to have a knack with a first aid kit, and patched up innumerable minor wounds right on the set!

Roar’s central characters are a family deliberately not dissimilar to the folks portraying them. Noel Marshall’s alter ego, Hank, departs farthest from reality, insofar as he’s a biologist rather than a third-string movie mogul. He’s living in Africa right now (someplace where they have Maasai— so Kenya? Tanzania?), studying the behavior of big cats with an eye toward future conservation efforts. When we meet Hank, he and his assistant, Mativo (Kenyan actor Kyalo Mativo, whom we’ll see again whenever I get around to Baby: Secret of the Lost Legend), are awaiting a visit from the committee that manages his research grant. It appears that most of the latter were unaware that Hank was conducting his studies by allowing scores of lions, leopards, cheetahs, and servals the run of his home and its grounds, let alone that he’d also imported a sizable contingent of tigers, jaguars, and pumas for the sake of comparison. Three members of the grant committee clearly did know what he was up to, though, and just as clearly disapprove strenuously. Those would be Prentiss, Frank, and Rick (animal handlers Steve Miller, Frank Tom, and Rick Glassey), who seem to represent the interests of the local farmers and ranchers— or the white ones, at any rate. Hank and his project don’t exactly cover themselves with glory on this occasion. When the committee delegation arrives to tour the facilities, he spends more time breaking up fights between lions than answering questions or reporting on his progress. And as if that weren’t bad enough, one of the tigers actually attacks his guests! There are no serious injuries (and it could be argued that the recipients of the minor ones brought it on themselves by acting like prey), but I expect Prentiss to find the rest of the committee much readier to accept his counsel at their next meeting to discuss Hank’s funding. Naturally the cats will be in big trouble if Prentiss gets his way and shuts the study down.

Meanwhile, the lions have a drama of their own. The boss of the pride is a huge, black-maned male whom Hank calls Robbie. He’s a benevolent ruler as lions go, and even gets along well with his housemates of other species. His position is endangered, however, by an equally formidable rogue male who has been hanging around the compound lately. Solitary lions with no lionesses to hunt for them must learn to be vicious indeed in order to survive, and Hank fears that if Togar (his name for the interloper) challenges Robbie for leadership, it will result in a fight to the death. (That, in case you were wondering, is why lions are so much bigger and stronger than lionesses, even though the latter are the breadwinners for the pride. It suffices for a female to be able to take down a zebra, but a male must be ready to battle another lion.)

However, the lion’s share (sorry, sorry) of Roar’s running time concerns neither of those conflicts, but rather what happens when Hank’s wife and kids come to move in with him at the villa. It’s been at least a matter of months, and more likely a year or two, since the scientist last saw his family. Relations had grown strained between him and Madeleine (Hedren, from Dark Wolf and The Birds), and they’ve been taking his work in Africa as a chance to play the “absence makes the heart grow fonder” card. It must have worked, because now Madeleine has packed up everything including her teen offspring, Melanie (Melanie Griffith, of Body Double and Automata), John (John Marshall), and Jerry (Jerry Marshall), and flown across the ocean to reunite with Hank. (Note that Joel, the youngest of the real-life Marshall boys, was wise enough to limit his participation in Roar to behind-the-scenes roles. He and Kyalo Mativo were among the very few people to work on this movie without ever being clobbered by a big cat.) There are just two problems. First, Hank hasn’t exactly been a great communicator during the separation, so his family have no idea that they’re about to be up to their eyeballs in lions, tigers, and whatnot. And secondly, Hank and Mativo get caught up in a comedy of errors involving two escaped tigers, thereby missing the rendezvous at the airport. Madeleine and the kids take the bus into the bush instead, arriving at the villa when all the cats except for a few pumas and leopards lounging quietly on the roof are out doing cat-things. That gives them plenty of time to settle in, both to the house and to a false sense of security. They’re totally unprepared when a horde of monster felines come strolling in like they own the place, and their behavior in response to the intrusion is practically a checklist of all the things you should never, ever do when confronted with an animal capable of eating you. Roar proceeds to become the only wilderness movie I’ve ever seen in which the audience is apt to start rooting for the malevolent poachers. Prentiss and Frank may be marked as the villains when they cut ties with the grant committee and set out to exterminate Hank’s cats on their own initiative, but there’s a distinct inadvertent note of “thank God somebody has the sense to put a stop to this madness” as the film cuts back and forth between their race to the villa against Hank and Mativo and the family’s travails against 150 of the class Mammalia’s most perfect killing machines.

I’ve watched Roar under two sets of circumstances now, each ideal in its own way. The first was at B-Fest, where the rambunctious— and largely unsuspecting— crowd was stunned into a silence punctuated only by exclamations of horrified disbelief. The second was at home, in the company of two argumentative housecats. Cat owners, I think, will get more out of Roar than those with pets of other species, because they’ll understand. They’ll recognize the lions’ and tigers’ behavior patterns from their own lives, together with the body language that indicates “DANGER! Pissed-off kitty ahead!” Most of all, they’ll go in aware of how much damage the seven-pound versions of these animals can inflict even when they’re not trying, simply through carelessness and failure to appreciate the fact that humans aren’t protected by thick fur and loose skin. They’ll therefore have a head start on imagining what the seven hundred-pound version is capable of.

What makes Roar such astonishing viewing— and what ultimately forced me to invent a brand new rating just for it— is the stark divergence between the movie that Marshall and Hedren set out to shoot and the one that actually emerged from their efforts. What was supposed to be a treacly, Disneyish family adventure flick, with an uplifting moral about humans living in harmony with nature, came out instead as the most authentically terrifying animal attack picture I’ve ever seen. They thought they were making Grizzly Adams, but they came within an ace of making Grizzly Man. You’ll marvel, slack-jawed, at the irresponsible, idiotic bravery of Marshall and his family as they tempt, taunt, and double-dog dare Fate again and again, for an hour and a half of screen time that translates into five fucking years on the shooting set. You’ll queasily examine every wound depicted, trying to spot the difference between the fake ones and the real ones. You’ll listen even more queasily to the soundtrack every time Melanie Griffith disappears beneath a pile of lions, pricking up your ears to discern whether this is the fabled scene in which the boom mike caught the sound of her face and scalp ripping as she was mauled. Most of all, you’ll learn the quick and easy way the respect for Africa’s most majestic predators that the Marshall family learned but slowly and very, very hard. And while I can’t predict whether you’ll do this, I know I spent the whole movie remembering something Richard Pryor once said in reference to his visit to newly independent Zimbabwe: tourists always want to fuck with the lions, until the lions slap the ass off of them.

All that said, the tale does have a happy ending. Commendably, Tippi Hedren ultimately figured out that this was no way for big cats to live. She arranged to keep the ranch compound where Roar was shot when she and Marshall divorced, and has since transformed it into a permanent sanctuary for big cats and other “retired” showbiz animals. The Shambala Nature Preserve, as it’s now called, houses about a third of its excessive late-70’s population, and those animals enjoy treatment and shelter that could not be further removed from the unsafe and insane conditions depicted in Roar. The Roar Foundation, which manages the preserve, retains the rights to the movie, and whatever royalties trickle in from it help finance the preserve’s upkeep. Sometimes Hollywood do-gooders eventually get it right after all.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact