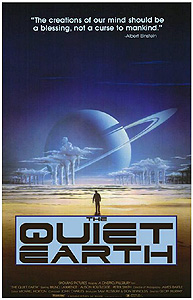

The Quiet Earth (1985) ****

The Quiet Earth (1985) ****

For the most part, the post-apocalypse movie comprised an intelligence-free zone during the 1980’s. Most filmmakers operating in the genre in those days were content to rip off Escape from New York and The Road Warrior over and over and over again, and to do so in a manner even less thoughtful than the unapologetically mayhem-driven movies they were copying. Consequently, when a film like The Quiet Earth comes along, and deals with the end of the world in a sober, non-action-movie fashion, the impression it makes is even more arresting than it would be solely on its own merits. Indeed, The Quiet Earth’s refusal to take its cues from The Road Warrior is doubly remarkable, for not only was it made in 1985 (the same year as Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome), it was shot just over the Tasman Sea in New Zealand. More amazing yet, there isn’t an atom bomb or a global war to be seen anywhere in its script or back-story.

It’s 6:11 in the morning in an obscure Auckland suburb, and a slightly doughy man in early middle age is lying in his bed, wearing only the laminated ID card on the chain around his neck; he doesn’t look well. At 6:12, something happens— something so strange, so indescribable, so totally unprecedented that for the remainder of the film, those who survive it will refer to it only as “the Effect.” One of the Effect’s effects would appear to be some sort of time-dilation, because when the unwell-looking man awakens, his clock still reads 6:12, despite the fact that the sun’s position in the sky more closely resembles 7:30. That’s his first hint that something isn’t right. The second comes when he calls in to work to announce that he’s going to be late (he’s proceeding at this point upon the assumption that his alarm clock just went haywire for an hour or so, even though it appears to be working now), and nobody answers the phone. There’s nobody on the street in his neighborhood, either, nor is there anybody behind the counter at the gas station where he stops to refuel his car. In fact, the whole station is empty— counter, garage, office, bathroom— but scattered all around are disturbing hints that it became empty very, very suddenly, and not by any normal means. All the way into downtown Auckland, it’s the same story. Cars, trucks, and road maintenance equipment lie abandoned on and beside the roads. Totally derelict houses present scenes of chaos which seem to suggest that their owners were removed from them as if by magic between ticks of the clock. Then our hero finds the crashed airliner. Among the debris, he can find not one body, nor even one piece of a body, but there is a basically intact set of empty seats with the lap-belts neatly fastened. That clinches it— something is definitely fucked up around here.

Fortunately for him, our hero is really Dr. Zac Hobson (Bruno Lawrence, whose other foray into the post-apocalyptic future— Warlords of the 21st Century— is a great example of what I was talking about in the first paragraph), a scientist on the staff of Auckland’s branch of the international Delenco corporation, and he’s spent the past several years working on a project that he was afraid might accidentally cause some sort of hitherto-unimagined catastrophe. When he finally arrives at the lab, Hobson has his suspicions confirmed; Project Flashlight was set in motion that very morning, and evidently there was an accident. The project head’s radiation-cooked corpse, still seated at the Flashlight central control panel, is the closest thing to another person Hobson has seen all day, and if the information from the lab’s computers is to be believed, humanity’s great vanishing act is a truly global phenomenon. Zac may well be the last person alive on Earth, and if he doesn’t find a way to escape from the lab (the main computer has just activated the automatic anti-contamination protocols, sealing the laboratory subbasement with Hobson still inside it), then even he won’t be around much longer. In desperation, Hobson improvises a bomb out of an oxygen tank, an acetylene tank, and a blowtorch, and takes cover in an office, hoping he doesn’t blow himself up while creating his exit door. After freeing himself from the lab, he devotes the rest of the day to seeking out any other survivors of the Effect.

Hobson paints signs on billboards. He lets himself into a radio station, makes a tape loop of himself announcing his name, address, and phone number, and sets it to broadcast continuously. He drives around town in a police cruiser, using its loudspeakers to carry his call for companionship from one end of town to the other. He even takes to wandering the streets of Auckland, blowing on a saxophone in the middle of the night. Five days later, a realization sets in. If Auckland is otherwise uninhabited, it makes no sense for Hobson to continue living in his little suburban cottage. After making a new contact information tape to broadcast over the radio, he trades up, moving into a huge, cushy mansion in the swankest part of town. He also starts looking for ways to amuse himself. He breaks into a shopping mall, and fills his new pad with clothes, furniture, TV sets, and— why the hell not?— a life-sized model auk covered with what look like real emu feathers. He plays with a train set at a toy store, and then repeats the game with a real locomotive. He requisitions department store mannequins with which to populate his house, and takes to acting out increasingly elaborate fantasies of the high life. Then, after about two weeks of all that, Hobson goes insane. With a woman’s silk slip and a purple sheet standing in for a Roman-style imperial tunic and toga, he declares himself president of the world before an audience of cardboard cutouts of historical figures (Hobson to Hitler: “I’m much too busy right now to waste time talking to you. Besides— you had your turn.”), at the precise moment that exactly the right machine breaks down at the local power plant, and the electricity goes out at last. A bit later, he bursts into a cathedral with a pump-action shotgun, demanding an audience with God. (Hobson, brandishing his gun at the altar crucifix: “Alright— if you don’t come out, I’ll shoot the kid!”) Only when he drives a stolen piece of heavy machinery over a pram that could possibly have held the world’s last baby (it didn’t, but that’s beside the point) does Hobson come to his senses. He goes to the beach, has a swim in the ocean, runs around naked on the sand for a while, and then heads back home with all the mad atavism worked out of his system. The following day, dressed in normal clothes once more (he’d been wearing that increasingly ragged and filthy slip ever since the night of his “inauguration”), Zac rigs up a giant gasoline generator to power his mansion, grabs himself a computer to hook up to the Delenco network, and gets down to the business of trying to figure out just what in the hell really went wrong and how he managed to get himself left behind.

That’s when the woman shows up. Her name is Joanne (The Returning’s Alison Routledge), and shortly after Hobson regains his mental balance, she walks into his house with a revolver in her hand. Zac and Joanne stare at each other for a moment, Joanne tosses the gun away (“It’s not real…” she admits), and the two of them rush across the room to embrace each other. In the days that follow, they become first friends and then lovers, and at Joanne’s instigation, they begin making a systematic search of the country, hoping to turn up any other people whom the Effect might have missed. (One oft-overlooked convenience about living in New Zealand is that scouring the land for survivors of the apocalypse really wouldn’t be all that big a job.) Eventually, they do indeed find one, a Maori named Api (Pete Smith). Api presents a fearsome appearance at first, cornering Zac in a side street with a ski mask over his face and an UZI in his hand, but he gets it through his head before long that the meeting of the last three humans in New Zealand (and at this point, I think it’s safe to presume that there are small numbers of survivors scattered over the rest of the world as well) is no occasion for gunslinging.

It would have been the easiest thing in the world for The Quiet Earth to turn into a Kiwi take on The Last Woman on Earth at this point, devoting the rest of the running time to Zac and Api’s struggle for decisive sexual possession of Joanne, but that’s not what happens at all. And hallelujah to that, by the way. There’s a bit of friction between the men, and a fair amount of it is related to the inescapably triangular relationship between them and Joanne, but that fortunately is not the point. The interpersonal drama from here out is merely the backdrop against which Zac and his companions must deal with a much bigger worry. Hobson has been checking in periodically with the computer at Delenco, and if he’s right, whatever Project Flashlight did to gum up the cosmic works has destabilized the fabric of the universe in such a way that he, Joanne, and Api can look forward to the periodic recurrence of the Effect unless something is done to reset the balance.

Most commentators argue that Joanne’s arrival— and if not hers, then certainly Api’s— marks the point at which The Quiet Earth takes a serious nose-dive. I disagree. “What would you do if you were absolutely the last human being on Earth” is, on its face, a fascinating question, which the first half of The Quiet Earth does a superb job of exploring, and it is indeed just a bit disappointing when that exploration is cut short. The thing is, though, that every one of us really already knows the answer to the question, and it’s a complete dramatic dead end: if you were the very last person in the world, sooner or later you’d go mad. And having grappled for some years with a similarly intractable— albeit obviously much less intense— degree of social isolation, I believe I can venture a pretty good guess as to the exact form which the last man on Earth’s madness would take. His good days (which would grow increasingly rare as time wore on) would be characterized by a sort of stoic resignation, made possible solely by a steadfast refusal to think about either past or future. On his bad days, he’d want to shoot his fucking head off, and on really bad days, he’d get as far as loading the gun and sitting for a while with his lips around the barrel and his finger on the trigger. As the bad days came to outnumber the good, he might even make a perverse sort of incentive program out of it, positing suicide as his reward to himself for lasting until some arbitrary future date (Christmas, new year, the next milestone birthday, etc.). And every once in a while, if only for variety’s sake, he’d probably go absolutely bonkers for an hour or a day or a week, alternately laughing, sobbing, and screaming uncontrollably, running around breaking shit at random just ‘cause he can. The most seriously psychotic episodes might be fun to watch, but— and you can trust me on this— the defining characteristic of a life of isolation is the sheer, open-ended pointlessness of it all, and open-ended pointlessness is not a good mood to strive for in a motion picture. Even Daniel Defoe had the good sense to realize that it would get awfully boring if Robinson Crusoe were really alone on that island; the eventual introduction of another survivor or two is a necessary dramatic step in a story like this one. The danger lies in taking that step and then running off in an insipid and annoying direction.

For me, the greatest strength of The Quiet Earth is that it avoids that pitfall. Look at The Last Woman on Earth for a comparison; a perfectly workable tagline for that movie could have been, “They’re the last three survivors of the human race… and they’re all assholes!” To a degree that is extremely rare in apocalyptic sci-fi (or in modern movies generally, for that matter) The Quiet Earth is about people rising above their differences— and not in some cliched, touchy-feely, politically correct, it’s-a-small-world-after-all way, either. The filmmakers accept and admit from the get-go that there’s really no good way to smooth out the complications that arise when Api enters the equation, but they refuse to cop out by setting the two men at each other’s throats in any sort of final showdown. Instead, all three characters must struggle to find a solution they can live with from the limited menu of unpalatable options before them. And if the ending smacks a bit of the deus ex machina, it is at least employed in a manner that seems to follow organically from what we already know about Zac and Api. I also deny the common complaint that the ending is in any way confusing, although I’m reluctant to explain why for fear of giving too much away. Suffice it to say that while The Quiet Earth goes out on an ambiguous note, it has already laid plenty of groundwork for its final scene, and anybody who honestly has no idea what is going on simply hasn’t been paying enough attention.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact