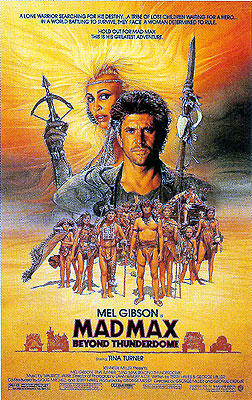

Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome (1985) **

Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome (1985) **

It’s amazing how sharp some of the dividing lines are in pop-culture evolution. I’m thinking in particular of how cleanly 1985 cuts off what we might think of as the Transgressive Age of exploitation movie history. All over the West (in which I’m including Australia and New Zealand, but not Latin America, which was following a schedule all its own), that was the year when horror, sci-fi, action, fantasy, and erotic cinema all started to lose their teeth. Everywhere you looked, there was less gore, less violence, less nudity, and less sheer twistedness than there had been just a few months before. And even when something truly warped and nasty did come along, it more often than not cloaked itself in a slicker of comedy, so that no one involved, creators and audience alike, had to worry about getting too dirty. Even something as sick as Re-Animator can plausibly claim to be all in good fun when it puts as much effort into winning a laugh as it does into winning a scream or a retch, however nervous those laughs are likely to be. So we shouldn’t be surprised that 1985’s Mad Max movie, Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome, is the one with the lovable dwarf, the reclusive tribe of innocent and fresh-faced post-apocalyptic moppets, and the spunky child aviator, nor should we be surprised that it would rather give its villains their comeuppance by dunking them in pig shit than by leaving them handcuffed to a burning car with a leaky gas tank.

Who can say how long it’s been since Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson, one last time) limped away from that overturned tanker truck full of desert sand, nigh the last survivor of the cunning bait-and-switch that bought salvation for an entire tribe of homesteaders? Long enough, anyway, for his police-issue crew cut to grow out into a mullet of majesty. Also long enough that gasoline-dependent banditry and scavenging off the corpse of the old world are no longer viable lifestyles. For although the vehicle Max now rides was plainly built to move under its own power, he has converted it to be drawn by a train of mules instead. Somebody must still be making high-energy liquid fuel of some sort, however, because Max is buzzed by a screwy-looking airplane flown by pith-helmeted weirdo Jedediah (Bruce Spence, who played an apparently different aviator in The Road Warrior) and his eight-ish son (Adam Cockburn, of Starship and The Girl from Tomorrow). Those two knock Max from his perch atop his wagon, incapacitate him, and steal both his vehicle and all the goods it was carrying.

Luckily for Max, there’s no way the father-and-son thieves are taking his stuff anywhere else but his own destination, the semi-subterranean Outback trading settlement of Bartertown. The only question is whether he can make it there on foot before Jedediah has a chance to sell everything he owns. The answer turns out to be “not quite.” That’s a serious setback, not only because Bartertown recognizes no law outside its own municipal limits (and therefore has no prohibition against dealing in stolen property), but also because the town official known as the Collector (Frank Thring, of The Man from Hong Kong and Howling III: The Marsupials) limits admission strictly to those who have something to trade. No welfare state around here! And if anyone doesn’t like that, then they can take it up with Ironbar (Rose Tattoo frontman Angry Anderson), the extremely short but also extremely tough motherfucker who serves as something like Bartertown’s chief of police. On this occasion, however, Ironbar has met his match, and the Collector enigmatically remarks that it looks like Max has something to trade after all.

The ruler of Bartertown, you see, has need just now for a man of such fighting ability. Not to keep the peace, you understand (Ironbar and the score or so comparable hard-asses under him do that perfectly well enough), but rather for a matter of internal politics. When Auntie Entity (Tina Turner, of all people) established Bartertown as an experiment in rebuilding, she began with a pure and simple vision: to create and maintain a stable forum for the buying and selling of goods and services. But while commerce may be among the most basic of human social interactions, it takes more than a marketplace to make a society— and once you have a marketplace, people who know how to create all the other stuff societies need can gain a lot of leverage. Take energy, for example. Max will have noticed by now that Bartertown has electricity, even though it has no more oil than anyplace else these days. The whole settlement is powered by methane gas derived from the manure of countless hogs. The machinery necessary to harness the power of all that pig shit was devised and built by an eccentric and truculent man who modestly calls himself Master (Angelo Rossitto, from Seven Footprints to Satan and Galaxina); he continues to manage the day-to-day affairs of the methane plant even today. And therein lies Auntie’s problem, because Master has been using his… well, mastery of Bartertown’s energy supply to assert himself over her in extremely public and humiliating ways. And before you start scoffing at an elderly dwarf posing any kind of threat to Ironbar and his goons, permit me to introduce Blaster (Paul Larsson, of Altered States and The Intruder Within), the surly giant on whose shoulders Master habitually rides. Blaster’s foot odor alone is more than a match for every man on Auntie’s payroll. But from the way Max handled Ironbar at the check-in counter, he might just be bad enough to take Blaster on. Now there’s no fighting allowed in Bartertown under ordinary circumstances— like another city notable called Dr. Dealgood (Cut’s Edwin Hodgeman) says, “Fighting leads to killing, and killing leads to warring, and that was damn near the end of us all.” But there is Thunderdome, the big, hemispherical cage in the center of the settlement where otherwise irresolvable disputes are settled man to man and to the death. If Max can get Blaster into Thunderdome— and if he can come out alive, obviously— then he’ll leave Bartertown with as much as he can carry of anything Auntie has to give him.

Picking a fight with Master/Blaster proves easy enough, especially once Max catches one of Master’s mechanics (George Spartels) tinkering with his stolen wagon. The Thunderdome bout itself is naturally more challenging, however. Max has a considerable edge in speed, agility, and cleverness, but Blaster is just too huge, strong, and resistant to pain and injury for his opponent to make much impression in the usual way. As Max observed, though, when an alarm fortuitously went off down in the methane plant, the giant is strongly affected by loud, high-pitched noises, and it just so happens that among the “never know when you’ll need it” stuff which Max carries around with him at all times is a piercingly shrill whistle. Once Max gets a long enough break in being pounded on to put that thing into his mouth, it’s all over. There’s one last turn left on this screw, however. When Max removes Blaster’s bucket-like mask-helmet to deliver the killing blow, he finds himself gazing into the glassy, vacant eyes of profound mental retardation. Slaughtering an overgrown toddler is not what he signed up for, but his refusal to take Blaster’s life does neither of them any good. Ironbar and his men shoot the giant full of arrows where he lies, and Max falls under Bartertown’s ultimate sanction. In this place, a contract is sacrosanct above all things, no matter how low-down, dirty, and immoral it might be, and he who busts a deal must face the Wheel. The latter is a spinner-like contraption marked with options like AQUITAL, DEATH, FORFEIT GOODS, AMPUTATION, and AUNTIE’S CHOICE. Max’s spin comes up GULAG, which is to say exile to the depths of the wasteland without food or water.

That’s when Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome turns into an entirely different movie. (And I mean that literally, as you’ll see in a bit.) At the limit of his endurance, Max is picked up and nursed back to health by a tribe of semi-feral children who live stone-age-style in a verdant valley supported by an oasis. The kids’ story is basically The Lord of the Flies, but with a more benign outcome. Their parents had all been refugees from the nuclear war that ended the old world (more on that later as well), but the airliner taking them beyond the reach of the devastation crashed in the Australian desert. After the survivors of the crash established themselves in the valley, Captain Walker the pilot led all the able-bodied adult passengers on a trek into the wasteland in the hope of finding a town or city that hadn’t been nuked into oblivion. The adolescent passengers were left behind to care for those too young, injured, or infirm to make such an arduous journey. In the years elapsed since then, each rising age cohort has gone off in search of the one before it upon attaining adulthood, and the children of the valley have handed down increasingly garbled versions of the community’s history to the next crop of little ones. The latter process has turned Captain Walker into a mythical messiah figure, and his hoped-for city into the paradisiacal Tomorrow-Morrow Land. And as for Max— what do you think this kiddie cargo cult is going to make of the first real grownup any of them have seen in their lives? Captain Walker’s supposed return gets the kids itchy to enter the promised land, and nothing Max can say will dissuade them. When the eldest of the girls (Helen Buday) takes her turn to lead the next search party despite Max’s insistence that there is no Tomorrow-Morrow Land, he realizes he’s got no choice but to stop the teens before they fall prey to the residents of Bartertown. That proves too optimistic a goal by half, but contact between the two societies introduces a new possibility. If Max and the kids can rescue Master from his rather miserable new life as Auntie’s slave-brain, the little old man might be grateful enough to bestow the fruits of his knowledge and intellect on the valley instead. Auntie isn’t going to like that very much, of course…

Let’s start with that nuclear war. You’ll remember from the previous two movies that the end of Mad Max’s world came in slow motion, as resource exhaustion led to social collapse, which led in turn to war for control of what little remained of the Earth’s dwindling bounty— a war which consumed the last of the very stuff it was fought to secure. As The Road Warrior told it, that war was rather obviously conventional in nature; a nuclear exchange would not have produced the sputtering halt to civilization which that movie’s opening narration so evocatively describes. Now, though, we’re told both explicitly and implicitly that the old world ended in atomic holocaust. The question is, why the change? I think this is a case of originators being spun by their copycats. When the success of The Road Warrior unleashed apocalypse mania on the world’s movie screens, few of the imitators had the patience for George Miller and Byron Kennedy’s gradual downfall of civilization, and in any case, people in the 80’s were rightly shit-scared of all those missiles the superpowers were brandishing at each other. Also, audiences abroad could be forgiven for not realizing that the landscape in The Road Warrior was so forbiddingly bleak and arid not to represent the footprints of a thousand H-bombs, but because most of Australia just looks like that. Consciously or not, Miller responded to the three years’ worth of rip-offs that intervened between this movie and its predecessor by assimilating his vision of the world’s end to theirs.

That’s disappointing, because the uniqueness of that original vision and the convincing thoroughness with which it’s developed are much of what sets Mad Max and The Road Warrior apart from the scads of cheaper, cruder, less carefully thought-out films that followed in their wake. At the same time, though, Beyond Thunderdome still fits fairly snugly into the picture formed by the series so far— or at any rate, the first half does. Bartertown is a completely logical next step in the progression from decay to collapse to rebuilding from the wreckage. The notion of using biologically renewable methane to support some faint semblance of a 20th-century standard of living in a world without fossil fuels makes sense on all sorts of levels, as does that of a protected space for commerce serving as a bridgehead back from savagery to civilization. Indeed, it’s psychologically astute of Miller to recognize that the lawless lifestyles depicted in the previous two films would at some point lose their appeal for many of their early adopters. Sooner or later, even the most enthusiastic cheerleader for survival of the fittest comes face to face with the reality that there’s always someone fitter than oneself. The Cargo Cult Kids have a certain social and historical logic about them, too, and their presence here shows that there are more ways to greet an apocalypse than are often supposed by the makers of After the End movies.

The trouble is that the kids belong in some other film than do Max and Barterown, so that Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome makes nonsense of itself by forcing them together. At the more literal, textual level, the rise of a society like we see in the green valley is a generational process, and if Max is still the 40-ish man we see here, then there haven’t been enough generations to accomplish all the forgetting and garbling and mythologizing that the Cargo Cult Kids have done. Also, if every bunch of teenagers old enough to mount a search of the desert does so (thereby depriving their own infant children of the benefit of their more reliable memories), then surely some of them should already have found Bartertown, and brought down upon the valley the avarice of Auntie Entity’s more adventurous subjects.

The other, and more damaging, incongruity is tonal. The valley represents an altogether gentler and more peaceful vision of life after the apocalypse, and in order to avoid the grim spectacle of its immediate destruction upon exposure to the crueler ways of the outside world, Miller has to hastily cover Bartertown in Nerf for its return to the story. The next time we see Ironbar, he’s become a comic, slapstick figure with the inhuman resilience of a cartoon character— a sort of live-action Wile E. Coyote. He and his soldiers must pose no credible threat to a train-load of children, nor can there be any prospect of him suffering permanent injury to anything but his pride during the climactic running battle. Auntie Entity, meanwhile, becomes completely incoherent as a personality, ultimately taking no action against the people who destroyed everything she’s worked to build since the fallout settled. There’s simply no squaring the woman who shrugs off the burning of Bartertown, the sabotage of its methane plant, and the defection of the one man alive who might be able to salvage the situation with the ruthless schemer who hires Max to eliminate her most dangerous rival in the first act.

The reason the pieces don’t mesh is that they weren’t originally intended to. The Cargo Cult Kids were to have been the focus of their own movie, but when George Miller and co-scripter Terry Hayes wrote themselves into a corner, the former suggested that the adult whom the children mistake for Captain Walker could be Max Rockatansky. From what I’ve read, it seems that the two plot threads effectively had different directors as well, with Miller taking the lead during the opening Bartertown segment, and co-director George Ogilvie handling just about everything but the climactic chase thereafter. I kind of wish I could see the movie Miller and Ogilvie initially set out to make. It probably wouldn’t really have been my speed, but I bet it would at least have been clearer than Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome on what it was trying to be.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact