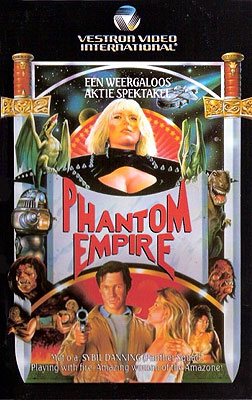

The Phantom Empire (1988) -**½

The Phantom Empire (1988) -**½

Whoops. I had meant to order The Lost Empire, Jim Wynorski’s cheesy 1980’s fantasy adventure movie in which pretty girls with big tits take on the mysterious final holdover of an ancient, non-human civilization. Instead, though, I mistakenly ordered The Phantom Empire, Fred Olen Ray’s cheesy 1980’s fantasy adventure movie in which the mysterious final holdover of an ancient, non-human civilization is a pretty girl with big tits. I can’t imagine how I got those two confused, can you?

Ray’s movie and Wynorski’s even sort of share the mechanism whereby the existence of well-concealed weirdness comes to the protagonists’ attention! The surface details are of course very different, but I think you’ll agree that The Lost Empire’s “Ninjas attack a jewelry store! Huh— I wonder what that was about?” and The Phantom Empire’s “Morlock attacks picnickers! Huh— I wonder what that was about?” fall into the same conceptual category. Now most people, upon reading about that Morlock attack in the daily newspaper, would probably focus on the Morlock itself, but to Denea Chambers (Susan Stokey, from The Tomb and Deep Space), the really salient fact is that the authorities who examined the creature’s carcass in the aftermath found that it was wearing half a million dollars’ worth of uncut gemstones on a cord around its neck. Denea figures that if she could find the thing’s lair, there’d probably be more where that crude necklace came from. She thinks she has a pretty good idea where to look, too, because her father was famed and respected paleontologist Daniel Chambers. When Denea was a kid, Dad spent some ten years of his life searching for any sign of the truth behind the legend of R’lyeh, a lost ancient city that was supposed to have existed somewhere in exactly the stretch of countryside where the picnickers had their strange encounter. He never found anything— but then, he never got jumped by a fucking Morlock either. If there’s one such creature prowling around those cavern-riddled canyons, there’s most likely a whole nest of the things, and a nest of Morlocks sounds to Denea like fairly convincing evidence of R’lyeh’s existence. Obviously Dad just never looked in the right cave.

With that in mind, Denea pays a visit to C and C Salvage, the proprietor of which, Cort Eastman (Ross Hagen, from Dinosaur Island and Star Slammer), was not merely an old friend of her father’s, but had actually assisted him at various points during his long, fruitless quest for R’lyeh. After all, who better to help her resume the search than a man who already knows all the places where the lost city isn’t? Eastman and his partner, Eddie Colchilde (Dawn Wildsmith, of Jack-O and Surf Nazis Must Die), agree to take the job, but Cort thinks some additional expertise will be needed. If he, Eddie, and Denea are going to be poking around in unexplored caves on the hunt for a fortune in native gems, then they’re going to need people who know the ways of rocks. Eastman therefore places a call to the Miskatonic Institute, and enlists the aid of fast-rising geology grad student Andrew Paris (Jeffrey Combs, from Castle Freak and The Frighteners) and mineralogist Artemus Strock (Robert Quarry, of Alienator and Hybrid). And then, playing a hunch that came to him while listening to Denea’s spiel, he brings her and Eddie with him to see a weird, gimp-legged hermit called Bill (Russ Tamblyn, from Necromancer and The Haunting), who might just be holding the most important piece of the whole puzzle.

You see, the reason why Bill is such a paranoid whackjob is because he took part as a young man in a prospecting expedition down a cavern not far from where Daniel Chambers would later try to find R’lyeh. He’s never told anyone exactly what happened— indeed, the vague and rambling account that he gives Denea, Cort, and Eddie now suggests that he may have blocked most of it out of his mind— but he was the only one who came out of that cave alive. While the prospectors’ attention was on the fabulous profusion of precious stones that they’d found in a certain underground chamber, they were set upon and slaughtered by… well, something. Something like diamond-mining Morlocks from R’lyeh, maybe? It should go without saying that no force on Earth could get Bill onboard for a return visit, but his ruined leg and PTSD nightmares aren’t the only souvenirs he brought home from the ill-fated venture. He also has the map that the expedition’s leader drew as they explored the cavern, and although it naturally isn’t complete, Bill swears that it’s accurate as far as it goes. Cort wants to get that map from the hermit, on the theory that it will lead him and his companions at least halfway to R’lyeh, but Bill refuses to part with it for exactly that reason. He doesn’t want anybody else’s deaths on his conscience. The wad of cash that Denea waves in Bill’s face would buy a whole lot of rotgut booze, though— maybe even enough to make his conscience pass out before he does. Bill inevitably relents, and when Denea, the salvagers, and the men from the Miskatonic Institute set out for the cave in the morning, they will indeed have the former prospector’s map to guide them on the first leg of the journey underground.

The Chambers party makes it an entire day and fifteen grueling subterranean miles before meeting their first Morlock— or more accurately, their first half-dozen Morlocks. It wasn’t the intruders from the surface that brought the creatures out in such force, however. They’d already been chasing a cute, busty cavegirl (Michelle Bauer, of Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers and Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula in Eight Legs to Love You), seemingly intent upon eating her, when they and the adventurers crossed paths. Strock makes an abortive stab at communication while the cavegirl cowers behind his companions, but he doesn’t get very far before Cort and Eddie start shooting. The salvagers’ assessment of the situation was probably more realistic than the professor’s anyway, since the next clash with the Morlocks ends with Denea kidnapped for roasting on a giant rotisserie which the creatures obviously didn’t slap together on a lark just for her. (In fact, the Morlocks didn’t build it at all. Sharp-eyed viewers can spot the very same rotisserie prop among the Spanish Inquisition’s instruments of torture in The History of the World, Part 1! This won’t be the last bit of production value that Fred Olen Ray scores on the cheap by renting it from some other outfit’s prop warehouse, either.) Eastman and the others rescue her, but the increasingly agitated Morlocks chase the surface folk still deeper into the Earth, far beyond anything marked on Bill’s map, until finally humans and Morlocks alike run afoul of… wait— Robby the Robot?!?! (See what I mean? Although this isn’t the original Robby the Robot, it is the somewhat redesigned 70’s-vintage replica suit that was used for episodes of “Project U.F.O.” and “Space Academy.”) It’s a near thing, but Denea eventually overcomes the mechanical menace by reflecting its own death ray back at it with the mirror from her makeup kit.

Although the salvagers are both remarkably incurious about what a robot is doing down here in the unexplored depths of a Southern California cavern, Strock and Paris recognize it as a mystery even more baffling than that of the Morlocks or the cavegirl— the latter of whom, obviously smitten with Andrew, has been tagging along ever since the explorers saved her from being eaten. Strock, unmistakably the brains of the operation by this point, makes the plausible inference that they must be getting close to their destination, and of course he’s exactly right. Around what looks like the very next bend, the cavern opens out into a gallery of such limitless, Pelucidarian size that the rest of the movie is shot mostly above ground in Bronson Canyon, with the obvious daytime sky explained away as the combined glow of a persistent volcanic plume and the copious overgrowth of bioluminescent fungus covering the who-knows-how-distant ceiling. Welcome to R’lyeh, everybody.

One thing you’ll quickly notice, even if the explorers themselves never do, is that there’s precious little sign of any city in this lost, subterranean city. But what R’lyeh lacks in urban development, it attempts to make up in development of an altogether different sort, for the place is home to an entire tribe of cute, busty cavegirls like the one we’ve already met, plus an extraterrestrial dominatrix played by Sybil Danning (Warrior Queen, Battle Beyond the Stars), who might be bustier than the whole mob of stone-agers put together. She landed on Earth untold ages ago, when R’lyeh was presumably still on the planet’s surface, but her spaceship was in no condition to take off again. In the intervening eons, she established herself as ruler of the cavegirl tribe and scourge of the Morlocks, but her main (if obviously none too effectual) interest has been in devising some way to repair her crippled vessel. Robby the Robot Mk II was her latest bid in that direction, its dual missions to extract whatever usable minerals there were to be had from the caverns linking R’lyeh to the surface, and to fabricate replacement spaceship parts from them. Now that the interlopers from upstairs have wrecked her robot, Space Dominatrix figures they owe her one— by which she means that she expects them to take its place on mining detail until either the ship is fixed or they drop in their traces, whichever comes first. Well, except for Paris, that is. Like the cavegirl, Space Dominatrix has taken quite a shine to Andrew, and has him earmarked to accompany her back to her homeworld as soon as the ship is ready. It should go without saying that nobody else likes those plans very much, and that Space Dominatrix will soon find herself facing a twofold mutiny and a simultaneous Morlock attack. Oh— and also stock monster footage from Planet of the Dinosaurs, because why the fuck not at this point?

It was Fred Olen Ray’s habit, during the 80’s and 90’s, to maintain a well-stocked junk drawer of treatments, sketches, script drafts, and even completed but disembodied scenes as a reserve against opportunity unexpectedly knocking. If somebody offered him a gig out of nowhere, or an actor he especially wanted to work with suddenly became available for a brief period in the near future, or some other filmmaker’s half-completed picture came up for sale, Ray could be reasonably assured that he had something lying around to fit the occasion. Most notoriously, he managed to crank out no fewer than five “John Carradine movies” after the actor himself was dead, thanks to a day’s worth of improvised footage that he shot in order to get his money’s worth after filming a few brief insert scenes to add marquee value to a cheap little clunker which he’d picked up for release through his American-Independent Productions firm. No one who has seen The Phantom Empire will be surprised to learn that it originated as a single scene destined for that junk drawer.

Ray was working on Commando Squad at the time, an uncharacteristically ambitious action movie for which he built an entire bad-guy military camp in the most arid section of Griffith Park— home to Bronson Canyon, the Vasquez Rocks, and several other oft-seen movie and TV shooting locations. Toward the end of the shoot, he got to thinking about how many times he’d seen this or that piece of the park, and remarked to Ross Hagen (who was playing one of the main villains) that it might be fun someday to try to shoot an entire movie without ever leaving its confines. Hagen liked the idea, and encouraged Ray to write an appropriate script, but that was as far as it went at first. Then on the last day of principal photography, the shack set where he was filming inspired Ray to shoot a junk-drawer scene about people buying a treasure map from a hermit. If that sounds familiar to you now, it should. For whatever reason, Ray and cinematographer Gary Graver became wildly excited about that scene watching the dailies, and decided not only to build their next project around it, but also that it and Ray’s notional “the many faces of Griffith Park” movie should be one and the same. Ten days later (ten!), Ray called out “Action!” for the first time on The Phantom Empire.

It’s only to be expected that a movie developed in such a feverish frenzy would come out resembling a fever dream. Not a single aspect of The Phantom Empire’s story will bear even the lightest scrutiny— beginning with the title, which is an absurdly grandiose way to describe Sybil Danning, a rented robot, and five girls in imitation buckskin bikinis. That title was well chosen in another sense, however, for it happens also to be the name of the 1935 Mascot Pictures serial that got cut down to form Radio Ranch. Fred Olen Ray’s Phantom Empire has a sensibility not half as far removed the earlier one’s as the five intervening decades would lead one to expect. Both draw from the same grab-bag of late-19th and early-20th century pulp fantasy tropes, and do so with a similar lack of concern for narrative cohesion. They each take an H. Rider Haggard-like incursion by Western explorers into a long-forgotten realm ruled over by an imperious woman, and transpose the setting from the African interior to an imaginary hollow beneath the American Southwest. And in a truly bizarre convergence, the producers of both Phantom Empires tried to goose their production values by renting used robot suits from MGM! The conceptual resemblances are too numerous to be coincidental, especially given how candidly Ray acknowledges his other major influences here. (My favorite such acknowledgement comes near the end of the closing credits, when Ray thanks “the City and County of Caprona” for their cooperation and assistance.) In any case, The Phantom Empire seems squarely aimed at fans of 1930’s fantasy-adventure serials in general— or perhaps more accurately, at fans of the idea of those serials, whether or not they’ve ever actually seen one. Mind you, that’s also one of the movie’s major weaknesses, because The Phantom Empire is never more faithful to the spirit of that model than when it runs out the clock as far as possible with distractingly frantic but actually pretty much pointless rushing about from one part of R’lyeh to another.

On the other hand, The Phantom Empire is well supplied with the most characteristic virtue of the cheapjack feature made almost purely on a lark, an infectious sense of how much fun the cast and crew were having on the set. One thing for which I will always give Fred Olen Ray credit is the palpable camaraderie that animates even his shoddiest work. This film is an especially strong example, due in no small part, I suspect, to its combination of ludicrously compressed schedule and intimate scale. Seriously, I’ve seen ska bands with more members than The Phantom Empire’s core cast, and it’s worth pointing out that all of them except Jeffrey Combs made movie after movie after movie with Ray throughout the late 80’s and early 90’s. There can’t have been much money in it for them, but the good vibes radiating out of this silly picture’s every frame no doubt give some indication of what kept Ross Hagen, Robert Quarry, Dawn Wildsmith, and the rest coming back for more.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact