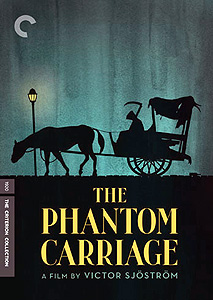

The Phantom Carriage/Körkarlen (1921/1922) ***

The Phantom Carriage/Körkarlen (1921/1922) ***

You know what you just don’t see anymore? Well, okay, yes— technically a lot of things. Monocles, white lipstick, Rambler Marlins, men named Hillary, whatever. But what I was thinking of specifically was didactic ghost stories. You know, like Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. Stories where the spirit world is overtly running its own supernatural Scared Straight program, bringing sinners, criminals, and assholes of every persuasion to grips with their moral failings via stiff jolts of uncanny, pants-shitting terror. This may sound odd coming from me, but I kind of miss those— at least the ones that are honest from the outset about their intentions, and don’t try to slip cloddish moralizing in under the radar. I suppose the logical way to broach the subject of didactic ghost stories around here would be to review one of the approximately 800,000 movies that have been made of A Christmas Carol over the past century, and I may yet get around to doing so one of these days. For now, though, I think that would be way too predictable. So instead, let’s head over to 1920’s Scandinavia, where some of the dourest and most downbeat moral meditations of all time were being dressed up with film’s then-unrivalled capacity for putting faces on all the devils, spooks, and witches with which writers of a certain stripe used to try scaring the peccable into behaving themselves.

The Phantom Carriage begins not with its sinner, but rather with its suffering saint. This is Sister Edit (Astrid Holm, of Witchcraft Through the Ages), and in a characterization gambit that now looks like one of this movie’s most eccentric features, she’s a missionary with the Salvation Army. Edit is dying of tuberculosis, her deathbed attended by both her mother (Concordia Selander) and her fellow evangelist, Sister Maria (Lisa Lundholm), and for some reason the thing she wants most right now is to see somebody called David Holm. Mom doesn’t like that idea, but far be it from Maria to obstruct a dying friend’s last wish. Maria is unable to locate Holm at the ramshackle tenement where he lives, but she does shanghai the woman she finds there (Hilda Bergström)— a haggard, intense, and prematurely aged lady of the sort that any child would find instinctively terrifying, who turns out to be the missing David’s wife— into paying a silent and profoundly uncomfortable visit to Edit. Clearly the two women have some sort of history together, although the obvious interpretation of the unspoken issue between them is probably ruled out a priori by Edit’s designated role in the story. Meanwhile, a man named Gustafsson (Tor Weijden) also goes out to hunt for David. (I never quite figured out what Gustafsson’s connection to the other characters was supposed to be; to judge from the uniform he generally wears, he could equally well be another Salvation Army missionary or some manner of liveried servant to Edit’s mom.)

As you’ve doubtless already surmised, David Holm is The Phantom Carriage’s Scrooge figure, the jerk-ass whose ways the spirits are fixing to mend. When we meet him (discovering in the process that he’s played by writer/director Victor Sjöström himself), David is hanging out in a cemetery, drinking and smoking with a couple of his buddies. This group aren’t exactly bums or hobos, but neither can we call them productive citizens with a straight face. Honestly, they rather remind me of Jocke, Lacke, and Gösta from Let the Right One In, since they apparently manage to maintain homes and families and the like, even though all we ever see them do at any hour of any day or night is to hang around getting drunk. The bars are all closed from the looks of things, but twenty to midnight is obviously way too early to hang it up and go home on New Year’s Eve; thus the bottle of wine and the cemetery. David is dominating the conversation, the nature of the occasion putting him in mind of a friend of his from back home in Upsala by the name of Georges (played in the ensuing flashback by Tore Svennberg). Evidently Georges, despite his usually jolly temperament, always became moody and morose on New Year’s Eve thanks to a story he heard as a child. According to this legend, the last person to die each year has to spend the next one driving Death’s carriage, roving all over the world to collect the spirits of the deceased for transport to the afterlife. It’s a miserable gig, not only because the soul in question is prevented from passing on to the next world him- or herself until being released from it, but also because time stretches out for the driver of the phantom carriage until that one year subjectively seems like centuries. Makes sense when you think about it— consider all the people who die in a year, and then imagine how long it would take to tramp from one death site to the next in a rickety, horse-drawn cart. New Year’s always brought the story to the forefront of Georges’s memory, and he could never properly enjoy himself while pondering the fate of those legendary unfortunates. That’s more than a little ironic in light of his supposed fate, for according to a rumor David heard recently, Georges himself died last year, on New Year’s Eve.

That’s when Gustafsson reaches the cemetery. Homing in on the sound of the drunkards’ conversation, he quickly finds Holm and delivers the message that Edit wants to see him. David refuses to have anything to do with her (although he won’t say why), and Gustafsson disgustedly returns the way he came. Holm’s friends, however, are even more incensed at his shabby treatment of a dying woman than Gustafsson, and a brawl breaks out among the three reprobates. In the heat of the moment, one of the other men cracks David on the head with the wine bottle, with results far closer to those you’d be likely to obtain in real life than one generally sees in the movies. David’s friends flee the cemetery when they realize that he isn’t moving, and Holm gradually succumbs to his head wound— expiring exactly at the stroke of midnight.

Why, yes— I do believe that is a phantom carriage clomping and squeaking up the path from the cemetery gates. And there’s old Georges at the reins, too! David doesn’t get it at first. He hasn’t yet noticed that he’s standing outside his body, nor has he processed the seemingly obvious link between what his old friend is up to and the legend with which he was so obsessed. Georges is very patient, though, and since David’s demise means he’s finally free of that godawful soul wagon, he’s got all the reason in the cosmos to relax and walk the other ghost through it all. Beyond that, Georges is just plain happy to see David again, although he does lament the circumstances of their reunion. Georges can’t help feeling like it’s all his fault, because he was the one who introduced David to his current (well, I guess it’s not quite current anymore) lifestyle…

…And with that, it’s time for another flashback. This one shows David as the doting father of two children, and happily in love with a wife who does not yet look like she woke up on the wrong side of the bed every morning for the last 20 years. It also reveals that he has a younger brother (Einar Axelsson, from Witches’ Night). That was all before Georges and his godless boozing. That was before a prison term for unspecified drunken loutishness; before depression over the disintegrating state of the family drove David’s brother to drink, too; before the bar fight in which the younger Holm boy accidentally killed a man, earning himself a life sentence in the very prison from which David was just then being released. The latter tragedy was enough to convince David that he had to get his shit together, but that resolve withered and died the moment he returned to his old apartment to find it deserted. There was no forwarding address left with the neighbors, and David was forced to conclude that his wife had packed up the kids and gone into hiding to avoid resuming her old life with him. His vow of reform gave way to a vow of revenge, in the service of which he set himself to scouring all of Sweden in search of his disloyal family.

In time, David’s quest led him to the town of his current abode, where he found his way to Edit and Maria’s newly opened Salvation Army mission; he would be the first indigent to receive the young women’s charity. (By the way, get a load of the sign beside the mission’s front door: Fralsningsarmen Slumstation! Nothing like good, old-fashioned Germanic directness, huh?) Said charity was not limited to a warm, dry, safe place to sleep, although that was all Holm actually asked for. While David slept, Edit stayed up half the night fixing the shit out of his torn, frayed, and shabby overcoat, heedless of Maria’s concerns over what sort of germs the visibly filthy drifter and his personal effects might be harboring. Does it count as foreshadowing when we already know explicitly what’s coming? Regardless, David’s reaction the next morning was not at all what Edit or Maria expected. Far from thanking the girl for her extra work on his behalf (to say nothing of the whole “giving herself tuberculosis” business), the ungrateful, spite-ridden bastard gleefully undid all of her repairs right in front of her before taking his leave of the Slumstation with a contemptuous guffaw.

Strictly speaking, it’s David’s turn now to drive the carriage, but given both their old friendship and Holm’s continued resistance to the reality of his situation, Georges decides to stick around to take the lead on what should properly be the other man’s first assignment. Fittingly, that assignment is to collect Edit, whose allotted span is just about used up at this point. Now David starts to get the picture, but rather than acquiesce to his destiny, he tries to run away— so Georges hog-ties him, and tosses him into the back of the cart. Edit, interestingly, is able to see her spectral visitors, although she doesn’t immediately recognize the trussed-up David. Not only that, but she knows what their arrival means. She pleads with Georges for one more day— not because she herself desires more life, but because someone she loves is in grave moral peril, and she cannot bear to depart without making one final, all-out effort to bring him to salvation. Yes, she’s talking about Holm, whom she inexplicably fell for when he showed up to heckle at a rally she and Maria were helping to run about a year ago. I guess the romantic comedy rules of attraction are in force even this far afield of the genre. The urgency Edit feels concerning David’s spiritual well-being is further intensified by her guilt over the outcome of her last attempt to intervene on his behalf, after discovering that he was married, and that his nomadic lifestyle was motivated by the search for his fugitive wife. Mrs. Holm had moved into town herself only a little ahead of David, and when Edit found that out, her do-gooder’s instincts led her to bring the estranged couple back together. Edit, in her innocence, imagined that David sought reconciliation, but as we know, he actually had something quite a bit different in mind. Rather explains Mrs. Holm’s treatment of Edit at the beginning of the film, that does. Anyway, hearing this outpouring of compassion and concern from a person he’s been nothing but shitty to since the day they met (and, let us not forget, whom he for all practical purposes killed) finally pierces the thicket of misanthropy that’s grown up around David’s heart since coming home from prison to an empty flat. Struggling free of his bonds, he throws himself upon Edit’s deathbed, and tearfully assures her that she has indeed reformed him at last— even if it’s technically rather too late to act on his reformation. With that, Edit breathes her last, and Georges gathers her aboard the carriage. Strangely, though, he does not immediately hand over the reins to the new driver, as one would expect now that the Edit business is sorted out. Georges has his reasons, however. He stuck around in the first place to provide moral support to his friend, and David is going to need plenty of that at the next stop on his itinerary: his own house, where his wife, in ignorance of his recent demise, is preparing to implement the final solution to her family’s misery.

Yeah, The Phantom Carriage turns fucking dark at the end there. It also unfortunately develops a plot-hole so big that the entire movie is in danger of falling into it, but I can’t explain what, why, or how without spoiling every last little thing. Suffice it to say that one of the reasons why “It was all just a dream” is such a popular cheat in moral spook stories is because certain denouements simply cannot be made to work without it. Be that as it may, the bleak tone is the key to The Phantom Carriage’s effectiveness, preventing it from coming across as just a silent, Swedish precursor to the American drug-panic movies of the 1930’s, with alcohol standing in for marijuana, heroin, or cocaine. Heaven knows it makes enough incursions into that territory, between David’s cartoonish misanthropy and Edit’s equally overbroad self-sacrificing holiness. The moment when Holm tears out all the repairs Edit made to his overcoat, just for the sake of being a dick to someone who helped him, is especially redolent of Reefer Madness and the like. But then the film will offer up something so totally over the top that it becomes disturbing and hilarious at the same time, like when David encounters a fellow tuberculosis sufferer at the Salvation Army rally, and sneeringly asks her, “Why turn away so carefully [when you cough]? I’m consumptive myself, but I cough in people’s faces to finish them off!” We see later on that he isn’t kidding, either, and that “people” includes not only his wife, but even his two daughters. It also helps tremendously that The Phantom Carriage has in the person of Mrs. Holm a character who consistently reacts realistically to the unrealistic behavior of the human straw-man arguments surrounding her. It’s like the poor woman slipped into the Twilight Zone somewhere along the line, and the constant toggling between the absurdity of the David-Edit story and the authentic misery that it produces in her life keeps both the movie and the viewer off balance in an interesting way.

The Phantom Carriage is also quite impressive technically, and it’s little wonder that Samuel Goldwyn would bring Victor Sjöström to Hollywood in 1924 (from which point he was generally credited as Victor Seastrom). The flashback introducing the legend of Death’s carriage is commendably spooky, and works on a remarkable number of levels simultaneously. There’s the design of the carriage itself, practical and understated, yet suffused with an air of forbidding antiquity. Combined with the similarly astute minimalism of the driver’s costume, it suggests something out of 14th-century plague art. The double exposure effects are unusually well done, too, not just perfectly calibrated with regard to the ghosts’ degree of transparency, but also exceptionally consistent from one scene to the next. Furthermore, Sjöström obviously put a lot of thought into the implications of the carriage not being part of the material world, which comes through most clearly in a bit which has the carriage drive to the bottom of a shallow cove to pick up the spirit of a man who drowned in a boating accident. There’s even a sound-design aspect at work in some of the ghost wagon’s subsequent appearances, although I can’t be sure whom to credit for it without knowing the provenance of the score that accompanied the print I saw. The death cart has its own musical cue, an attenuated violin squeal not unlike that which served as the Joker’s sonic signature in The Dark Knight, which interplays with Sjöström’s acting in the scene where Georges comes for him in the cemetery to suggest the horrid, unearthly squeaking of the vehicle’s suspension. Although The Phantom Carriage is by no means a horror movie in the modern sense, those early scenes of Death’s coachman at work carry much the same uncanny charge as the Yet to Come segments in the best film versions of A Christmas Carol. Indeed, you might almost say that Georges functions like all four of Scrooge’s spectral night callers rolled into one.

Another place where The Phantom Carriage earns distinction is in its extraordinary structural sophistication. It isn’t just the reliance on flashbacks, which was unusual enough in 1921. There are also interludes within flashbacks, as when David’s reminiscence about Georges triggers a flashback to a bygone New Year’s Eve, which leads in turn to a dramatization of Georges’s story about the death cart. And what’s more, the flashbacks do not come at all in strict chronological order, so that our understanding of the story and of the characters’ motivations is constantly evolving as new pieces of the puzzle fall into place. I can’t think of anything else I’ve seen from this era that was so confidently non-linear, and even looking back from today I can think of only a few films that use non-linearity to such good effect.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact