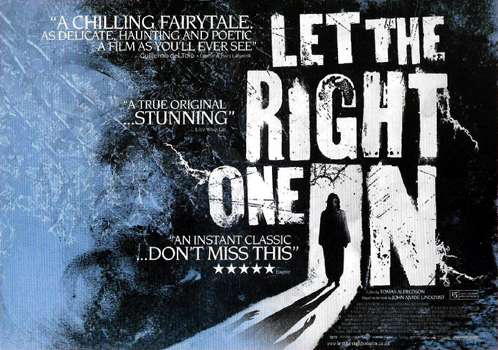

Let the Right One In / Låt den Rätte Komma In (2008) ****

Let the Right One In / Låt den Rätte Komma In (2008) ****

There may be no truism less true than “the book is always better than the movie.” I’ll concede that the book is better than the movie more often than vice versa, but my experience (based on many years of reading a fuck of a lot of books and watching a fuck of a lot of movies) puts the balance closer to the 60/40 range. Furthermore, when the movie turns out better, it’s frequently a lot better— and why shouldn’t it be? After all, there’s no obvious reason why prose writers should be any less prone than their screenwriting counterparts to botching a good idea, losing the thread of a story in a warren of distracting and irrelevant subplots, or blowing an ending with cheats and clichés. Meanwhile, adapting an existing story offers a perceptive writer a chance to spot the things that didn’t work in the source material, and to fix those that are susceptible to fixing. Few book-movie dyads that I’ve encountered illustrate the point more sharply than Let the Right One In— which is all the more remarkable given that John Ajvide Lindqvist wrote both the novel and the screenplay to this first film version. (A second, English-language version entitled Let Me In was released two years later by a newly resurgent Hammer Film Productions. So nice to see that once-great and oft-resurrected firm produce something more worthwhile than a short-lived television series or a cheesy, self-congratulatory “greatest hits” clip-show for once.) The novel is a passable pulp potboiler that derives most of its limited entertainment value from its exaggerated misanthropy and over-the-top ugliness. It’s the literary equivalent of a Cannibal Corpse album— a clumsy but adequate C+ read for fans of stories about awful people doing awful things to each other until most of them are dead, but a sure bet to repulse absolutely everybody else. The movie directed by Tomas Alfredson, on the other hand, is something much smarter, much subtler, and much more worthy of lasting interest. Far from the gleefully crass mean-spiritedness of the book, the filmed Let the Right One In is a terribly sad tale with a happy ending more horrible than any of the unhappy conclusions it might have come to instead.

In a glum and dispirited-looking apartment complex in the glum and dispirited-looking Stockholm suburb of Blackeberg, there lives a glum and dispirited pre-adolescent boy by the name of Oskar (Kåre Hedebrant). Those of you who already know that Let the Right One In is a vampire movie would be well justified in panicking at this point, assuming that the ensuing 115 minutes are going to be more emo than Guy Picciotto with cancer of the puppy. Don’t do that, though— not even if you also already know that a human-vampire love story of sorts is in the offing. This is going to be a lot closer to The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane than to Twilight, I assure you. Besides, Oskar has reasons for being so down all the time, above and beyond a certain innate tendency toward melancholia. His parents are divorced, and his mother (Karin Bergquist) tries to compensate for a work schedule that keeps her apart from him more than she’d like by being wearyingly overprotective when she is around. His father (Henrik Dahl) drinks too much, and his loose and easygoing parenting style (so unlike his ex-wife’s) continues to spark acrimonious inter-parental arguments over the telephone whenever Oskar goes to stay with him for a few days even now. And being both timid by temperament and small for his age, Oskar endures a lot of bullying at school, especially from a classmate named Conny (Patrick Rydmark) and his sycophantic sidekicks, Andreas (John Sömnes) and Martin (Mikael Erhardsson). Conny’s favorite game is to corner Oskar out of the sight of grownups, and make him buy his way out of a beating by impersonating a pig. Yeah, that would make a lot more sense if Oskar were abnormally fat instead of abnormally skinny, but there’s rarely much to be gained from asking for logic in junior high bullying; maybe Conny just really liked Deliverance. Oskar, incidentally, has a favorite game of his own. He likes to spend his evenings in the park-like courtyard behind his apartment block, pretending that one of the trees is Conny, and rerunning each new day’s biggest humiliation— except that the reenacted versions invariably end with Oskar stabbing Tree-Conny repeatedly with the hunting knife he keeps hidden in his bedroom.

In fact, that’s exactly what Oskar is up to the first time he meets Eli (Lina Leandersson), the girl about his own age who just moved into the flat next door in company with a middle-aged man— his name is Håkan (Per Ragnar), but you’d never know that from the film itself— whose relationship to her is tantalizingly unclear at first. An odd kid, this Eli, even with Oskar for comparison. She’s remarkably stealthy, to begin with. One minute, Oskar’s all alone in the courtyard, stabbing the shit out of his tree, then the next thing he knows, there’s a little girl standing on top of the jungle gym. Her conversational style is a marvel of doing it wrong, too, as when she announces, completely without provocation, “Just so you know, I can’t be your friend,” and then refuses to elaborate as to why that might be. But all in all, the weirdest thing about her might be her response when Oskar asks if she isn’t terribly cold, hanging around outdoors on a Swedish winter’s night without coat, hat, scarf, or gloves: “I don’t know— I guess I don’t remember how.” Wait— she’s forgotten how to be cold?! The hell?!

Meanwhile, Håkan is up to no good at all. He goes out at night to other communities in Stockholm’s western suburbs to waylay young people, incapacitate them with halothane, and slit their throats, collecting the blood in a big plastic jug. And although Let the Right One In plays it coy for a while about the reasons why, it’s immediately apparent that Håkan is somehow committing these crimes on Eli’s behalf. Nor do Håkan’s activities go unnoticed, even if no one is yet in a position to tie the killings to their perpetrator. Word that there’s a serial killer at work outside of Stockholm is just about the hottest topic of conversation everywhere, even among the crowd of eccentric middle-aged sad-sacks who seem invariably to be hanging out at the local pub, regardless of what time of day it is. Their unofficial leader, Lacke (Peter Carlberg), actually tries to rope Håkan into the recurring conversation one afternoon, not even beginning to suspect a connection between the murders and the secretive, introverted new guy in town. The pub gang is about to become directly tied to the murders, however, for Håkan fucks up one night, and is unable to bring Eli her usual jug of blood. When that happens, Eli takes matters into her own hands, and sets a trap in the shadow of a pedestrian underpass. Plausibly pretending to be an injured victim of one of Håkan’s attacks, she lies in wait for some well-intentioned passer-by to attempt her rescue. The doomed good Samaritan happens to be Lacke’s best friend, Jocke (Mikael Rahm), and when he picks Eli up to carry her to the hospital, she bites him in the jugular vein, and won’t let go until he succumbs to blood-loss. Eli does a very odd thing, too, when Jocke finally drops dead in the snow; she wrenches the corpse’s head around 180 degrees, more or less cleanly severing the spinal cord. Sated on the dead man’s blood, and visibly more comfortable and at peace than she had been before, Eli returns to the flat she shares with Håkan, and sends him back out to dispose of Jocke’s body— which he does by dumping it in the hot spring that feeds a nearby lake, the only bit of water anywhere around that isn’t yet covered with an impenetrable layer of ice. What neither conspirator realizes is that although Håkan disposed of Jocke cleanly enough, there was a witness of sorts to Eli’s attack on him. Gösta (Karl-Robert Lindrgen), another of the pub regulars and a sort of male equivalent to the traditional Crazy Cat Lady, was looking out his living room window when Eli sprung her trap, and while it was too dark outside for him to discern any details, he saw well enough to know that Jocke, incredible as it might sound, was murdered by a child.

But to return now to Oskar, he and Eli soon find that they are becoming friends after all, regardless of the girl’s pronouncement earlier that such a thing was impossible. It’s here that Let the Right One In first stakes its claim to genuine brilliance, serving up the most natural and credible cinematic treatment of first love I’ve seen in years, while simultaneously making it ever plainer to us (if not necessarily to Oskar just yet) that Eli is really a centuries-old vampire and dropping enough vague hints at her history with Håkan to suggest that this might not perhaps be her first love after all. Eventually, three plot threads coalesce that will, in their respective ways, become the parallel axes of the film. On one side, Håkan gets caught while gearing up to bleed another boy for Eli in the local gymnasium, and although he first disfigures himself with acid and then allows Eli to kill him in the hospital in order to prevent anyone from tracing him to her and uncovering her involvement, he is unable to do anything about the loose ends represented by Jocke’s body lying at the bottom of the hot spring and Gösta’s knowledge that Jocke, at least, was not killed by the faceless man arrested at the gym. Then Eli, forced to fend for herself, attacks Lacke’s girlfriend, Ginia (former children’s television hostess Ika Nord), but is prevented from finishing her off the way she did Jocke and Håkan. Lacke is going to have a lot to think about once Ginia starts turning into a vampire herself, and it’s a safe bet he’s going to see the obvious connection with Gösta’s story about a savage, throat-biting child. And while all that’s going on, Eli encourages Oskar to stand up to Conny and his little gang, which has the unforeseen effect of pulling Conny’s sociopathic teenage brother, Jimmy (Rasmus Luthander), into the boys’ feud. With Håkan dead and Lacke actively on the hunt for her, Eli is going to be needing a new Renfield. And with Jimmy out to get him, Oskar could really use a superhumanly strong protector who is more or less impervious to switchblades, no matter what his stance on vampirism may be in the abstract.

You have to admire the moxie of anybody who isn’t afraid to film a junior-high love story that ultimately hinges on the question of whether the two kids at its center are willing and able to kill for each other, and you really have to admire the moxie of someone who’ll do it seriously and honestly, without glossing over or shying away from any of that premise’s implications. That’s what most makes the film version of Let the Right One In so drastically superior to the book; on the printed page, Lindqvist was basically just out to shock, by whatever lazy or overwrought means necessary, but the movie insists upon treating all of its characters as if they were real people— even if they technically haven’t been for about 200 years. The alterations, both in surface-level plotting and in tonal effect, are plainest in the relationship between Håkan and Eli, in Håkan’s fate after his arrest, and in the treatment of Eli’s origins and back-story. In each case, the movie aims for the heart by telling us almost nothing, while the book aims for the gag reflex by telling us more than we ever wanted to know.

In the novel, Håkan is a homosexual child molester, and Eli adopts him, so to speak, just a short while before the start of the main action. We get to see how desperately he lusts after Eli (which isn’t as out of character as it sounds, but we’ll get to that in a bit), how adroitly and callously Eli exploits that lust, and how he deals with the fact that she won’t put out for him except in the most trivial ways. We get to see the erotic undercurrent he experiences in the murders he commits, however much he might deny that in his own mind. We get to see him buy a bathroom-stall blowjob from a pre-teen male prostitute whose pimp has smashed all of his teeth out so as to enhance the experience for his customers, and then congratulate himself on his philanthropy for secretly slipping the boy a big enough tip to pay for dentures one of these days. Book-Håkan is a vile bastard, and he only gets viler as the story progresses. Movie-Håkan, on the other hand, is a poignant figure. We don’t know anything about him except that he kills for Eli, and although the hints we are allowed don’t directly contradict anything in the novel, they are wide open to— and indeed actively encourage— an altogether more sympathetic interpretation. There are no little boys in the film, no years spent as a homeless wino after getting fired from his teaching job, no leers in Eli’s direction. All we have is a soft-spoken 50-ish man with a perpetually doleful expression and an irrepressible aura of defeat about him. And crucially, the vibe in those scenes where we see him and Eli together is clearly one of love— not sexual, not paternal, not platonic, but instead love of some terrible, unclassifiable species that no one should ever have to endure. Part of that, obviously, comes from the quietly brilliant acting by Lina Leandersson and Per Ragnar, but it also emanates from the lingering power of two exchanges of dialogue in the scene that sets the stage for Håkan’s final hunting trip. The scene opens with Eli seemingly trying to talk Håkan out of undertaking the night’s mission, to which he responds with painful matter-of-factness, “What else am I good for?” It ends a few minutes later with Håkan asking a favor of Eli: “That boy— please don’t see him tonight, alright?” Eli has nothing to say in reply either time. Again, nothing is stated explicitly. What it looks like, however, is a glimpse into the only possible future that Oskar and Eli could ever have together, which conversely suggests that the two kids’ hesitantly budding relationship is a reflection of Eli and Håkan’s past. Eli, in her own words, has been twelve years old for a long time; has Håkan spent the four decades since he was that age too in her devoted service, his obvious love for her becoming more glaringly impossible with each winter that comes and goes? The book says no, but the movie leaves that question studiedly unanswered.

Doing so requires the most overt departure from the print version of the story. In the novel, Håkan’s attempt to sacrifice himself for Eli is markedly less successful. He melts his own face off with acid and allows Eli to feed from him in the nearest he’ll ever come to the consummation he so ardently desires, but Eli is stopped at the last moment from wrecking his body sufficiently to prevent him from succumbing to vampirism. If it were handled the way it was in the book, keeping that turn of events would have put paid to any subtlety or ambiguity in the Eli-Håkan relationship, for Lindqvist didn’t just bring Håkan back as a vampire. No, he brought him back as a mindless and inexplicably indestructible vampire ass-rapist, a veritable Jason Voorhees of forcible buggery! And as if that weren’t already more than enough, this walking punchline to a dirty joke you’ll thank the gods you never heard the rest of spends the remainder of its existence homing in relentlessly on Eli, following its distended rigor mortis erection like an obscene divining rod! Suffice it to say that I can think of no good use for any aspect of this subplot, and that dropping it in its entirety was the second-smartest thing Lindqvist and Alfredson did in translating Let the Right One In to celluloid.

The smartest, period, was excising all but the faintest hint of Eli’s personal history, and for that, we can apparently credit Alfredson alone. As in the book, there was originally to have been a flashback in which Eli telepathically induces Oskar to experience her memories of how she became a vampire; perhaps aptly (as you’ll soon see), the finished film bears a prominent continuity scar marking the flashback’s removal, as Alfredson left the setup for it intact. The mind-meld would have revealed that the human Eli was in fact a pubescent boy, the vampire who transformed him having preferred to drink his blood from dense capillary networks rather than from arteries (if you catch my drift), and I do not exaggerate in the slightest when I say that making Eli’s sex-change explicit would have flat-out ruined the movie. I say that not because I have anything against boy-love, but because that twist (at least as presented in the book) is so stupid on so many levels that I scarcely know where to begin. For one thing, it’s pointless. Learning that Eli isn’t just talking about being a vampire when “she” warns Oskar that she’s “not a girl” doesn’t make any difference to Oskar’s feelings for “her.” It also doesn’t resolve any looming character issues, or indeed impact the story in any way at all. It’s the very worst sort of plot twist, the kind that exists solely for the sake of short-term shock value. Beyond that, it doesn’t make any logical sense. What imaginable motive would Elias have for posing as female for the rest of eternity just because some kinkster vampire ripped his junk off in order to bleed him? He was going to be twelve years old forever either way, so it’s not like a normal sex life would ever be in the cards for him, you know? You can’t even reasonably argue that it was a trick to buy an extra couple years of inattention from any given population or social circle, because the same people who would expect Elias to start growing facial hair sooner or later would also expect Eli to acquire tits and hips eventually. And in case you somehow failed to notice this when you were in sixth grade, girls generally mature earlier than boys anyway! Finally— and this is the biggie— Eli wouldn’t have fooled Oskar for a second if she were really a boy, however successful the ruse might have been with adults. After all, the whole point of puberty is that people who haven’t yet undergone it, male or female, have very little in the way of secondary sex characteristics. Children have no trouble discerning each other’s sex, though, and it isn’t just because boys and girls are traditionally expected to dress differently. In the movie, fortunately, the sole remaining trace of Lindqvist’s most mind-boggling narrative blunder is a moment when Oskar peeps on Eli while she’s changing her clothes. For a second or two, we see what he sees, but all that really comes across unless you know from the book what you’re supposed to be looking at is that Eli’s crotch is horribly scarred. To be perfectly crude, it’s unmistakably a girl’s crotch underneath the makeup prosthesis (guys’ pubic bones sit at a completely different angle to their hips), and the scars are in the wrong place for what they’re meant to represent anyway. Consequently, it’s easy enough to ignore the scene’s intended meaning, and chalk the scars up to some atrocious but non-specific sexual trauma. I really can’t overstate what a positive effect that downplaying of the twist has on Let the Right One In.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact