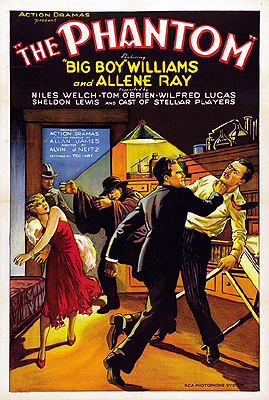

The Phantom (1931) -*½

The Phantom (1931) -*½

From time to time, a movie will leave me in despair of my communicative abilities, as I ask myself how in the hell I’m ever going to explain this. It’s just something that comes with my plot of cinematic territory, and I’m used to it by now. However, it is extremely unusual for a mere spooky house mystery to drive me to such straits. The Phantom has done it, though— and what’s more remarkable still, it appears to be precisely the rote ritualism of the genre that gives The Phantom its power to baffle and bewilder. You know those machine learning experiments, in which a computer is programmed to create something after being exposed to thousands of examples of the desired article? Well, The Phantom plays like the outcome of one of those. All the familiar elements are here, but they’re tossed together without apparent rhyme or reason to form something very strange indeed.

We begin in a maximum security prison, where a criminal known only as “the Phantom” is about to be sent to the electric chair. And here already comes the first false note. How could the Phantom have made it all the way to Death Row without anyone ever learning who he really is? The newspaper reporter sent to cover the execution notices as he arrives a strange, unmarked aircraft circling the prison, but the warden doesn’t think anything of it when it’s brought to his attention. He should, though, because that plane is the decisive element in the Phantom’s audacious and improbable escape plan. There’s a train that passes by the prison every day at about this time, you see, on tracks not 20 feet from the outer wall. When the train arrives today, the Phantom (evidently enjoying one last visit to the exercise yard before his date with Old Sparky) scales the wall with inhuman alacrity, leaps to the roof of the train, then flies away to safety in a rig suspended from the unmarked airplane’s undercarriage. The reporter sounds simultaneously thrilled and rueful when he calls his editor, Sam Crandall (Niles Welch), with the story.

Now that he’s free, the Phantom immediately sets to work on a scheme to avenge himself upon John Hampton (Wilfred Lucas, from Just Imagine and the 1923 version of Trilby), the district attorney who put him away in the first place. And this being the kind of movie that it is, he makes sure to announce these plans via telegram not only to the target himself, but also to the relevant police precinct. The Phantom’s telegrams are highly specific, too, stipulating not merely the date on which he intends to strike, but also the place (Hampton’s own house) and the very hour (half past midnight). Luckily for the criminal, though, the cops return the favor of the sporting chance he’s given them by assigning Sergeant Pat Collins (Tom O’Brien, of The Last Warning and The Private Life of Helen of Troy) to protect the DA. Collins will spend the rest of the film deciding, usually on no discernable basis whatsoever, that each new person he meets is secretly the Phantom, starting with Hampton’s butler, James (Billy Griffith).

But let’s return for a bit to Sam Crandall. He has a personal interest in the Phantom case along with a professional one, because Hampton’s daughter, Ruth (Allene Ray, from the silent serial versions of The Green Archer and The Terrible People), is the star writer for his paper’s society page. Also, it happens that Sam is in love with her. Ruth, however, is in love with Dick Mallory (Guinn “Big Boy” Williams, the kind of B-Western star who would often find himself playing second banana to a trick dog), a hapless galoot whom Crandall recently hired. Indeed, Ruth and Dick are secretly engaged to be married just as soon as he works his way up to a position that will support a family. Crandall isn’t happy to learn that, but he’s a standup guy. As soon as Ruth makes her intentions known to him, Sam quietly puts Dick on the Phantom story as a chance to prove himself, and thereby to secure Ruth’s future.

The trouble is, writer/director Alvin J. Neitz keeps that quiet from us, too, at this stage of the game. He also introduces Mallory as the unheard half of a telephone conversation, so we’ve never seen him before when he sneaks into the Hampton mansion and confronts the DA in his study at precisely the hour appointed for the Phantom’s attack. We know Dick can’t be the Phantom, though, because… well, just look at him. Squinty little pig eyes, ill-fitting suit, no attempt at a disguise, Texas accent— not a bit of that satisfies the genre’s norms for a criminal mastermind, especially not when we’ve already seen somebody else in a black cloak and a wide-brimmed hat (Sheldon Lewis, from The Monster Walks and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) skulking around the property like the world’s shoddiest counterfeit of the Bat. When Dick makes his admittedly suspicious entrance, the natural reaction is not, “*GASP!* It’s the Phantom!” but rather, “Who the fuck is this butt-monkey?”

And that, as you might have guessed, is the point at which The Phantom turns into Spooky House Mad Libs. Sergeant Collins peacocks his way around the Hampton mansion, blustering at everybody. Lucy the maid (Violet Knights, the director’s sister) and Shorty the chauffeur (Bobby Dunn) are noisily terrified again and again, pretty much any time anything happens. There’s much running up and down the secret stairs that communicate between the mansion’s basement and the back of the closet in Ruth’s bedroom, and only slightly less scaling and descending the similarly secret ladder that links the basement to who knows where. The guy in the black cloak and hat continues skulking hither and yond all over the house, never to any apparent purpose. Mallory creeps about too, exhibiting only slightly more conscious intentionality than Cloak Guy. And for all his doubly telegraphed menace, the Phantom lets the hours dribble idly by, making nary a move against his supposed target. Eventually, Cloak Guy mounts a desultory and easily thwarted attack on Ruth, who subsequently reports to Dick that her assailant said something about her making an interesting subject for Dr. Weldon’s experiments— which is curious, because we saw the whole altercation, and Cloak Guy definitely didn’t say that.

Okay, so who the hell is Dr. Weldon? Dr. Weldon (William Gould, from Flesh and Fantasy and The Strange Case of Dr. Rx) is the director of the private sanitarium on the other side of the woods from the Hampton place, and since there’s clearly no danger of a plot breaking out at the mansion any time soon, Dick and Ruth commandeer her father’s car to see if they can induce one over there instead. Before you get excited about having seen the last of Lucy and Shorty, though, notice that they’re hiding in the limo’s back seat. Anyway, Dick, Ruth, Lucy, and Shorty are taken aback to discover that the sanitarium is virtually empty. In fact, on their first sweep through it, the only person they meet other than each other is a loony Swede by the name of Oscar (William Jackie), who leads them on several wild goose chases around the building thereafter (while inevitably loading up his dialogue with as many mispronounced J-words as possible). At one point, however, the reporter and his companions do prevail upon Oscar to introduce them to the doctor— who almost immediately begins dropping hints that he’s a doctor of the mad persuasion, and who concurs in the end with Cloak Guy (who turns out to be another of his patients) about Ruth’s suitability as an experimental subject. Ruth faints from fear at just the perfect moment to facilitate her being whisked upstairs to Weldon’s secret trepanation lab in the attic, and more Spooky House Mad Libs ensue. Finally, Dr. Weldon stands revealed as none other than the Phantom himself— except that there’s no plausible way for that to be true within the context of what we’ve already seen.

Like I said, if you subjected an AI to 40 days and 40 nights of riffs on The Bat, The Monster, and Seven Keys to Baldpate, then set it to compose one of its own, I’m quite certain the result would be very much like The Phantom. It isn’t just that everything that happens in this movie happens in half a hundred other spooky house mysteries, although that certainly is true. What makes The Phantom such an extraordinary assemblage of clichés and commonplaces is that it contains no evidence that its creators ever put thought of any kind into how or when all those recycled story pieces would be used. The easiest way to see what I mean is by trying to construct a coherent mental picture of Dr. Weldon’s criminal career. We know that he operates a private lunatic asylum, where he and an accomplice called Alphonse perform medical experiments on people. We know that Weldon was caught, tried, convicted, and imprisoned, and we can extrapolate from his sentence that the crimes for which he was busted included murder or rape. We also know that the authorities somehow never figured out his identity after he was apprehended, even though Weldon was a public figure with neighbors, colleagues, and patients who were all acquainted with him and his sanitarium— and we know that none of the latter ever heard about Weldon’s arrest, trial, or imprisonment, even though the Phantom was, in his own way, a public figure as well. We know that Weldon has exceptional athletic prowess, both from seeing him in action during his escape and from hearing the police chief describe the Phantom as “a human tiger” in an all-points bulletin about him thereafter. And of course we know that Dr. Weldon was dubbed “the Phantom” in the first place— as opposed to, say, “the Butcher,” “the Surgeon,” or “the Vivisectionist.” You see how these data points form, at best, two clusters? One for a stealthy, insinuating archthief on the Fantomas model, and another for a Dr. Ziska-like medical madman? And do you see also how they can’t really be made to overlap? The only way I can account for it is to assume that Alvin Neitz was sampling indiscriminately from the biggest spooky house hits of the preceding decade, giving no fucks whatsoever for how the elements should be combined.

Beside all the foregoing, it feels rather superfluous to attack The Phantom’s technical incompetence, but it has plenty of that, too. There’s no shape or structure to the story, so that most of the film’s mercifully brief 61 minutes are devoted to repetitious and apparently aimless roaming through the ill-lit hidden passages of the Hampton house and the Weldon sanitarium. No one in the cast has any charisma, and Allene Ray displays a level of discomfort in front of the camera exceeded only by Bo Derek. Neitz was content to let flubbed lines stand, just so long as it was apparent by the end what the offending performer had meant to say, and half the cast consistently calls Dr. Weldon “Dr. Walden” instead. The comic relief is exhaustingly broad even by the standards of 1931, and there’s an inexcusable amount of it. Even with only an hour to fill, Neitz gave Lucy and Shorty approximately one out of every three scenes— easily enough to make me cry nepotism, given his close relationship to Violet Knights. The climax devolves into such a disorderly display of poorly-choreographed fisticuffs that even the average William Beaudine Western would give The Phantom the stinkeye. Even the most impressive sequence in the film, the Phantom’s escape from prison, is marred twice: first by being lifted whole from some other picture (a silent adventure serial, I’m guessing), and then again retroactively, when Neitz makes no effort of any kind to create the slightest resemblance between William Gould and the stuntman who performs the prison break. I notice that very shortly after making The Phantom, Alvin J. Neitz started calling himself “Alan James.” I think I’d change my name, too, if I had a few turkeys like this on my resumé.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact