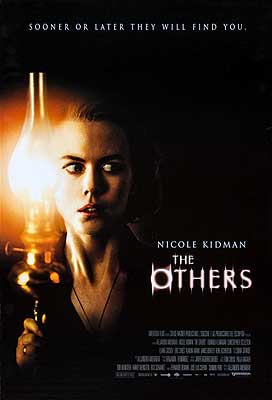

The Others (2001) *****

The Others (2001) *****

I’ve pretty much given up on Hollywood when it comes to making movies that are anything more than empty eye candy in the genres that interest me. Granted, 1999 proved to be a good year for horror, both quantitatively and to some extent qualitatively as well— that year gave us The Sixth Sense and Ravenous, after all. Meanwhile, 2001 is shaping up to be a big year for science fiction, although it’s worth pointing out how many of this year’s sci-fi flicks are unnecessary and mostly unwanted remakes— Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes springs instantly to mind, as do the upcoming remakes of Rollerball and The Time Machine. But then, out of nowhere comes The Others, easily the best haunted house movie in twenty years. Imagine, a major-studio horror movie with a sane budget, an intelligent story, a capable cast featuring only one famous star, and no distracting special effects! In 2001! There is, however, one obvious explanation for this extremely aberrant phenomenon: The Others, though still a Hollywood movie in the broad sense, was shot in England by a Spanish director.

The story here is as complicated as the most Byzantine William Castle plot. It begins with the arrival of three people— a middle-aged woman named Bertha Mills (Fionnula Flanagan, from the 1973 TV version of The Picture of Dorian Gray), a man of comparable years by the name of Tuttle (Theater of Blood’s Eric Sykes), and a teenager named Lydia (Elaine Cassidy)— at the secluded mansion of a wealthy young mother named Grace (Nicole Kidman) on the isle of Jersey. It is late in 1945, and Grace’s husband has yet to return from the war; she is thus in serious need of assistance around the house, and has placed an advertisement for household help in her local newspaper. Bertha, Lydia, and Tuttle are all experienced domestics, and they have come in answer to Grace’s ad.

It is immediately obvious that something isn’t right about this situation. Grace insists on keeping her house darker than most people could possibly live with, and she is equally adamant about a bizarre rule according to which no door in the house may be opened unless the one behind it has been closed. As it happens, her outlandish lifestyle is calculated for the benefit of her two children, Annie (Alakina Mann) and Nicholas (James Bentley), both of whom are morbidly sensitive to light— prolonged exposure to direct sunlight will literally kill them! But there’s still more weirdness afoot. Grace herself is extremely religious, in an unhealthy way that skates right up to the very edge of fanaticism. The fact that her previous staff of servants quit en masse without a word of warning or explanation some time ago also suggests that life with Grace and her family is not something to be undertaken lightly. Annie keeps hinting at some extremely bad business in the family’s past (“Mommy went mad,” is all she’ll say on the subject). And finally, there is even slight cause to suspect that the trio who have turned up on the doorstep looking for work might not be entirely kosher themselves. Grace’s ad, you see, hasn’t yet been published, and all three applicants used to work for the former owners of the house. Bertha attempts to use the latter fact to explain her presence in the face of the former (she knew the mansion had changed hands, and figured the new owners might be in the market for some experienced servants), but as we shall soon see, there has to be more at work here than that.

The first indications that Grace’s house is haunted surface on Bertha’s first full day in her employ. Annie drops several hints over breakfast that weird things have been going on in the old mansion, and have been for some time. Most alarming are her cryptic references to a little boy and an old woman, whom she claims to have seen and spoken to, despite the fact that no one meeting their description ought to be in the house. Grace predictably takes these tales to be the product of the girl’s “overactive” imagination, and on the theory that playing make-believe is indistinguishable from lying in the eyes of the Lord, attempts to bludgeon Annie’s fantasies out of her with the cudgel of scripture. But no matter how many hours of what would otherwise be her leisure time Annie spends reading aloud from the Bible, she still insists that she has seen and talked to an old woman and a little boy named Jacob. And what’s more, she has her brother half-convinced of her tales, too.

Eventually, even Grace begins noticing strange manifestations in the house. At first, she believes that it is Annie or Nicholas she hears crying in the far corners of the mansion, and that Lydia is the one responsible for all the heavy-footed gallumphing she hears from the upper floors when she is downstairs. But neither child will admit to crying, and one afternoon Grace sees both Bertha and Lydia outside during one of the stomping episodes. Finally, Grace is convinced that someone else is in the house when she follows the sound of footsteps upstairs and sees light emanating from beneath the door of a locked storage room. Annie is sitting at the top of the stairs reading at the time, and when pressed (the girl is understandably reluctant to tell her mother about such things now that she knows doing so will get her punished), she admits that she saw someone enter the room. But there’s no one inside when Grace goes to investigate. A series of similar incidents leads her to order a thorough search of the house, from attic to cellar, but this proves no more effective at flushing out the intruders than her earlier search of the junk room.

Meanwhile, Bertha and Tuttle have got us wondering about them again. Tuttle has been using leaf litter from the trees to hide a small group of graves located in a remote corner of the grounds. Moreover, he and Bertha periodically have short and mysterious conversations regarding Grace and her opinions of the manifestations in the house. Obviously, these two are up to something.

Then something wholly unexpected happens. Grace, now totally convinced that her house is haunted, sets off for town to fetch the local priest, but gets lost in the woods because of the dense fog. While she wanders about trying to get her bearings, she encounters a tall, gaunt man with a heavy backpack and haunted eyes. To Grace’s astonishment, it’s her husband, Charles (Shallow Grave’s Christopher Eccleston), returned at last from the war. It turns out Charles was a resistance fighter, and not a regular soldier, and with no proper mechanism for demobilization, he’s evidently been roaming the island, shell-shocked, in search of his home ever since the war’s end. But his strange behavior in the days following his return home leads one to wonder if maybe there isn’t something more seriously wrong with him than battle fatigue.

And that’s all I’m going to tell you. If the post-release history of The Sixth Sense is any indication, there will be plenty of loose-lipped people around, eager to give away every little kink in The Others’ serpentine second half, even without me contributing. So from this point on, I shall bite my tongue, and limit myself to urging you to see this exquisitely crafted, delightfully creepy little movie for yourself. Alejandro Amenábar has done a fantastic job with this, his first English-language movie. His script and direction are both top-notch, displaying a strong sense for the history and conventions of the genre (note the pleasing hint of Poe in the children’s mysterious illness, for example), along with an admirable willingness to put those conventions to other uses than those for which they were designed. Amenábar has also clearly paid close attention to Robert Wise’s The Haunting; he brings to The Others the same careful use of light and shadow, frame composition, set design, and sound that made Wise’s film arguably the horror masterpiece of the early 1960’s. Like Wise, Amenábar has figured out that it isn’t so much the unseen, but rather the heard that is scarier than the seen, but he also understands that there are times when only a good visual shock will do.

The other important way in which The Others stands above the rank and file of contemporary horror films is its exceptionally successful casting. To begin with, I was blown away by how good Nicole Kidman is in this movie. She’s perhaps a bit glossy for a woman of the mid-40’s, but she is otherwise fully believable, and she has the best fake British accent I’ve heard in many a year. Grace is a complicated character, with whom Amenábar asks us to sympathize even though we can’t fully trust her, and I’m frankly amazed that a modern celebrity actress like Kidman is able to pull such a multifaceted role off. Even better is the team of unknowns who make up the rest of the cast. Like Kidman, Fionnula Flanagan and Eric Sykes are required to be likable and potentially dangerous at the same time, and they are able to make their performances work with significantly less screen time than Kidman gets. But most remarkable of all is Alakina Mann, as Annie. Annie is an extremely intelligent little girl, but also just the slightest bit bratty, with a taste for mischief and a wit that is acerbic far beyond her years. She enjoys tormenting her brother, but she also clearly loves him, and when the strange goings-on in the mansion turn from vaguely sinister to outright threatening, she displays real concern for his safety. She’s also, in her way, the most practical character in the film, and she has absolutely no tolerance for bullshit. In short, she’s very much the sort of child I myself hope to have one day, and she makes for an extremely refreshing change of pace from the type of juvenile that usually crops up in the movies. And Mann hits every note in her character’s very wide psychological and emotional range perfectly— expect great things from this kid if she continues to pursue an acting career.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact