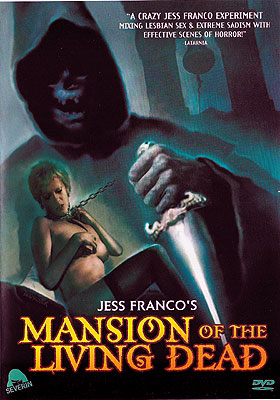

Mansion of the Living Dead/La Mansion de los Muertos Vivientes (1982) -**½

Mansion of the Living Dead/La Mansion de los Muertos Vivientes (1982) -**½

In an interview segment appended to the nifty-as-usual Severin DVD of Mansion of the Living Dead, Jesus Franco describes this movie as a freeform meditation on themes drawn from the work of poet and novelist Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer. Bécquer isn’t an author I’ve read, and I know almost nothing about him beyond that he lived during the 19th century and that he’s greatly respected in his native Spain— the kind of writer whom you can’t escape from the Spanish school system without encountering at least once. My ignorance of Bécquer and his writing means that I can’t confidently guess what Franco might have had in mind by linking him to Mansion of the Living Dead. Just the same, though, I also can’t shake the suspicion that he was having us on at least a little, because for a film supposedly rooted in the classics of 19th-century literature, Mansion of the Living Dead sure does look like a shitty rip-off of Tombs of the Blind Dead and its sequels. I mean, I guess it can be both— and if anybody was going to pull a stunt that ridiculous, Jesus Franco would be the one. Even if it’s true, though, I’m not sure the highbrow connection adds much to the sometimes hilarious, often excruciating, and always baffling experience of watching this film.

Truth be told, to call Mansion of the Living Dead a Blind Dead rip-off is a tad simplistic even without invoking Gustavo Bécquer. Better to say that it’s like a cheesy European sex farce ran aground on a Blind Dead rip-off, leaving castaways and undead Knights Templar alike completely flummoxed as to what to do with each other. At the core of the story are four girls from Munich, vacationing together in the Canaries. All four work as topless cocktail waitresses (“It’s in right now,” one of them explains), and they’ve been saving up their tips all year for this trip. Consequently, they’re more than a little annoyed when the Aguila Playa hotel turns out to be off-season quiet when they get there. How are they supposed to have fun on this holiday with no pool parties or beach parties to join, and no hot young guys to bang? Also, what’s this the concierge (Antonio Mayans, from The Inconfessable Orgies of Emmanuelle and Revenge in the House of Usher) tells them about the hotel being booked so solid that they’ll have to pair up in rooms at opposite ends of the immense building? If the hotel is that packed, then where the hell is everybody?

On the other hand, the widely dispersed accommodations and the apparent lack of eligible studs aren’t necessarily the calamities they seem at first. That’s because Candy (Lina “Candy Coster” Romay, of The Perverse Countess and Tender Flesh) and Lea (Mari Carmen Nieto, from Alone Against Terror and The Sexual Story of O) have a lesbian letch for each other, and they didn’t want those other two prudes cramping their style anyway. It’s funny to hear them say that, though, because Mabel (Mabel Escaño, from Open Season and Doctor, I Like Women— Is It Serious?) and Caty (Elisa Vela, of Fury in the Tropics and Intimate Confessions of an Exhibitionist) have a Sapphic fling of their own going, and are just as happy to have a buffer zone between them and their prudish friends. One wonders where the two pairs got their ideas about each other.

Anyway, the girls spend their first day on the island getting increasingly creeped out by their surroundings. It isn’t just the hotel that’s strangely empty. The beach is just as deserted once they see it, nor are there even any pleasure boats visible out on the water. In fact, the only other person they see face to face apart from Carlo is Marleno (Albino Graziano, from Oasis of the Zombies and Night Has a Thousand Desires), the Aguila Playa’s loony groundskeeper. His idea of maintaining the landscaping seems to consist mostly of perving on the girls while they sunbathe, eavesdropping on them through the flimsy doors to their rooms, and generally making a nuisance of himself. But creep or not, it isn’t Marleno who lobs a meat cleaver at Candy and Mabel from a balcony on one of the upper floors— he’s watching them from behind a beached rowboat at the time. The targets of the cleaver-toss are unnerved, naturally, but not so much as to countenance abandoning their holiday.

Early the next morning, Lea leaves Candy drowsing in their room in order to explore a primo photography location to which Carlo alerted her. That would be the ruined Medieval abbey of Almaíta—which is to say that it’s Mansion of the Living Dead’s equivalent to Amando de Ossorio’s Berzano. Lea’s excursion goes about as well for her as a visit to Berzano would have, too, and for much the same reason. But in the manner of Horror of the Zombies, we don’t actually get to see what fate befalls this first casualty. That means we also don’t get a good look yet at the dimestore skull masks that pass for zombie makeup in this turdburger, but just you wait!

Mabel is the next to disappear. It’s hard to believe this based on the noontime sunlight streaming in through all the windows at the time, but she is awakened in the middle of the girls’ second night at the Aguila Playa by the sound of a woman moaning. You’ll probably assume, as I did at first, that she heard Lea’s anguished voice carrying across from the abbey, but it turns out there’s something much closer at hand to account for the noise. In any case, when she goes to investigate, Mabel encounters Carlo, whom she promptly seduces. Carlo has business that prevents him from consummating that seduction on the spot— he says he has to go feed a sick woman— but the pair make plans to meet again at 10:00 the following morning. Mabel might decide to skip out on their date, though, if she could see what “feeding a sick woman” entails. Somewhere in the hotel, Carlo is keeping a 30-ish blonde prisoner, chained up nude in bed. We’ll later learn that her name is Olivia (Eva León, from The House of Psychotic Women and Autopsy), and that she considers herself (perhaps delusionally) to be Carlo’s wife. Be that as it may, she and Carlo have about the most fucked-up, perverted love/hate thing going that I’ve seen in quite some time. So perhaps it’s less surprising than it might otherwise have been when the venue for Mabel’s date with Carlo turns out to be the zombie-haunted abbey, or that Carlo has a doppelganger among the undead Cathars (heh) “living” there. The Cathar abbot passes sentence upon Mabel as soon as she is presented before him: she is to be executed in a state of mortal sin, so that she may be received immediately into the service of Satan. In practice, that means the zombie monks kill Mabel in the midst of gang-raping her. Might have known these guys could find a way to put a woman through that, and still wind up at the conclusion that she was the one sinning, huh?

From here on, Mansion of the Living Dead becomes much more specifically Candy’s story. She too gets woken up one midnight by Olivia’s sobbing, only she successfully follows the sound to its point of origin. That means Candy becomes our proxy ears for the captive woman’s tale of how she arrived in her present predicament, although her narrative is sufficiently jumbled and inconsistent that its reliability may be open to question. Olivia also reveals that she was responsible for that business with the cleaver, even if it was Carlo who actually threw the thing. She was jealous of the vacationers, whom she suspected Carlo was lining up to replace her. Nor was Olivia entirely off-base in that suspicion. When Candy has her own run-in with Carlo, he immediately identifies her as the reincarnation of the witch who cursed the monks of Almaíta to their present state. (They’d been burning her at the stake at the time.) Carlo believes that Candy therefore holds the power to release the Cathars from undeath by helping him to satisfy the conditions of the witch’s curse, and because he hopes to win her cooperation on that score, the reception she ultimately receives at Almaíta is at least a tad more favorable than Mabel’s.

Mansion of the Living Dead does have one genuinely effective aspect. Franco shot the film at a real resort hotel on Gran Canaria during the off season. It was a vast place, but also one that we would naturally expect to see thronged with people, all of them engaged in some manner of lively, escapist pursuit. To see it so totally empty is eerie as hell, and only becomes more so as the film wears on. It’s one of Franco’s best realizations of his recurrent theme of places existing outside of time to bridge the worlds of the living and the dead, precisely because a huge hotel on the beach must be the unlikeliest of all suspects for such a haunted locale. A pity, then, that it should figure in so ludicrous and incoherent a movie as Mansion of the Living Dead.

The basic defect here is that the two halves of the premise are irreconcilably at cross purposes. The drive to keep finding fun and funny excuses to get the cast out of their clothes and into bed together is absolutely toxic to the somber mood of slowly mounting dread required of a proper Blind Dead copy. To cite only the most egregious example, at a point when Caty’s and Candy’s lovers have been missing without a trace for something like twelve and thirty hours respectively, their response is to take each other to bed in lieu of the vanished girls. How are we supposed to take the looming Cathar menace seriously if the fucking protagonists won’t? But at the same time, how can we appreciate the girls’ determination to let nothing interfere with their quest for orgasms with so much necrophilic rape-murder going on in the background? The irony here is that there’s a perverse sense in which four titty-bar waitresses on a pansexual fuckcation in the tropics are the perfect protagonists for a horror film on the themes with which Franco is working in Mansion of the Living Dead. The undead Cathars represent the power of religious extremism to pervert and destroy men’s emotional and moral faculties, especially as pertains to love and sexual attraction. Candy and her friends, meanwhile, embody the very thing religious extremists tend to hate most, even as they crave access to it: radically liberated female sexuality. In a more carefully serious film— or alternately in a deliberately satirical one— the conflict between them could be made to carry some real intellectual weight. As it is, though, Mansion of the Living Dead is just stumbling around in clown shoes.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact