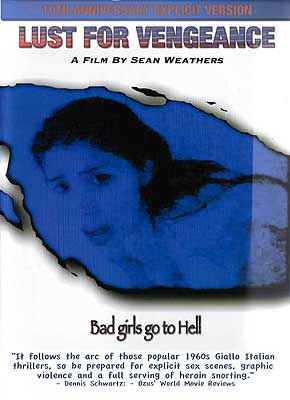

Lust for Vengeance (2001) *½

Lust for Vengeance (2001) *½

In the special features appended to the tenth-anniversary edition of Lust for Vengeance, writer/director Sean Weathers sketches out a story that has considerable personal resonance for me. He too spent his adolescence avidly consuming slasher movies, until eventually he fancied himself something of an expert on the things. But then one day— he doesn’t say when, but I’ll bet it coincided closely with his introduction to the internet— he learned something new and astonishing about the genre he thought he already knew inside and out. Before any of the movies he was accustomed to thinking of as the pioneers of the slasher film, there had been these things called gialli. Intrigued by the notion that Italians had been making something functionally equivalent to slasher movies for a decade and a half before they caught on over here, Weathers immediately began delving as deeply into the giallo as his budget and access would permit. (Assuming that he had relocated from Boston to New York by then, I enviously picture him spending a lot of time and money at Kim’s Video, filling up his living room with Dutch-subtitled bootlegs of old British pre-cert tapes.) By his count, he watched over 100 gialli before the mania passed— and then he decided to try his hand at making one.

I like that story not just because it echoes my own experience (although my version obviously ends with me reviewing gialli instead), but because of the insight it offers into Weathers’s creative thinking. You see, Lust for Vengeance bears only the most distorted resemblance to any giallo I’ve ever seen— or to put it another way, what stands out to me when I watch a giallo is obviously not what stood out to Weathers. But knowing what this movie was supposed to be, I can see how he got here. While the good-for-nothing cop, the black-gloved killer, and the visual refrain of the latter crossing names off his enemies list are the only instantly recognizable giallo elements, other features of Lust for Vengeance resolve themselves into parallels or analogues for giallo commonplaces if you stare at them long enough.

The least gialloid thing about Lust for Vengeance is its structure. The out-of-order segments following individual characters look more like Quentin Tarantino than Dario Argento. But if you mentally reassemble the pieces, you get the story of how Jennifer (Michelle Soto), evidently a fashion model or some such thing, is murdered after a one-night stand with the narcissistic Anthony (Walid Smith), and how four friends whom she lost touch with years ago become the killer’s subsequent targets— and then Lust for Vengeance starts to look more like its inspiration.

You can also perform a similar trick with the four nearly plotless character studies that follow Jennifer’s murder in the timeline, but precede it in the film. Normally, you would expect at least one of the dead girl’s associates— most likely Lisa (Julia Cornish, from Midnight Kiss and Void), since her story comes last in “objective” order— to attempt catching her killer, especially since the cop on the case (Brian Dusseaux) is an obvious ass-clown whom I wouldn’t trust to catch a cold. Detective White even hands them a suspect in the form of Michael Richards, the sociopathic classmate who raped Jennifer when he and the girls were all in junior high together, and whose long stay in juvenile jail came courtesy of Lisa and the others’ testimony. They do no such thing, however. Instead, Jennifer’s friends mostly just take lots of drugs and have lots of sex (which, remarkably, is choreographed and shot in such a way that it’s impossible to tell whether or not the couplings are simulated). What the hell kind of murder mystery is that?! Consider the lifestyle of the typical giallo character, though, and then think about Weathers’s circumstances. Where was he supposed to find misbehaving glitterati and corrupt aristocrats in Brooklyn in the days before hipster gentrification? The relentless focus on the girls’ lives of squalid debauchery is meant to establish them as low-rent counterparts to, for example, the staff of Christian Couture in Blood and Black Lace. Thus Stephanie (uncredited for some reason) is embroiled in an unwanted one-way romance with a poetry-slamming panty-sniffer (Sergei Burbank). Thus Beth (Pierre-Sophia Petion) never met either a dick or an intoxicant that she didn’t want inside her. Thus Anna (Tumaini) struggles with bulimia and dates a second-string pro football player (Carlito Rivera)— the closest thing to royalty that this milieu will support.

Even the movie’s second-most annoying visual tic reveals a hidden basis in giallo once you know what to look for. Those awful color filters that turn the entire screen alternately blue, green, purple, yellow, and red? They’re as close to a Mario Bava lighting scheme as Weathers could come with the equipment he could afford. After all, you can’t put a gel on a desk lamp.

It’s a good thing Lust for Vengeance is so compelling as an intellectual puzzle, because damn this movie is awful. It’s almost indescribably ugly, for one thing. Weathers and cinematographer Aswad Issa had used and reused all of these interiors on a multitude of projects by this point (most of them never completed, mind you), and their boredom with the settings is palpable. The lighting problem that marred House of the Damned is even worse here, because now there are colors to wash out— or at least there are whenever Weathers isn’t applying his sad counterfeit Bavavision technique. And truth be told, the Bavavision bits are even worse, because for the first half of the film, they just look like color-correction mistakes. Furthermore, the most irritating quirk of Issa’s camcorder is much more obvious in Lust for Vengeance than it was in House of the Damned, where the stark, overly contrasting black and white tended to monopolize the processing power of the viewer’s visual cortex. I’m not even sure how to explain the defect without a working technical knowledge of videotape, but it’s analogous to low frame rate on film. Whatever the process is whereby videotape refreshes the image on the screen, Issa’s camera triggers it so infrequently that there’s a persistent visual stutter throughout the movie. The action onscreen is like a clock whose second hand advances in discrete ticks, versus one that moves in a continuous sweep.

On less technical fronts, the acting in Lust for Vengeance ranges from dreadful to catastrophic. Dialogue is clunky and unnatural. Character behavior defies rational explanation. The endless sex scenes are interesting only at the level of “are they or aren’t they?” and the gimmick adopted to establish Beth’s promiscuity— playing several sex scenes at once so that they each fill another’s negative space— is downright headache-inducing. Speaking of gimmicks, the Pulp Fiction-like time pretzel serves almost no purpose but to emphasize that the segments could be shown in virtually any order without making a bit of difference to the narrative. And if Jennifer’s lesbian tryst on the beach with a character (I’m pretty sure this is Nefra Dabney, of Hookers in Revolt) who has never been mentioned before, and will never be mentioned again, strikes you as belonging in some other movie, that’s because it does. The scene was shot for an aborted project called Escape from Bloodbath Island.

I want to end this review on a positive note, though, so let me tell you about the one time when presenting the segments out of chronological order means anything. Lisa’s segment and Anna’s are the two that most overlap each other in time and space, and Weathers gives them to us consecutively, with Lisa coming first. However, the Lisa vignette has a gap in the action right before its final scene. When she wakes up just before dawn, goes into Anna’s room, and finds the latter girl dead beside a note from the killer reading, “Aren’t you glad you didn’t turn on the light?” the message comes across merely as a generic attempt to terrorize the surviving roommate. Only in Anna’s tale do we see enough to grasp the note’s full significance: not only was Lisa in the apartment while her friend was being murdered, but she was in the very bedroom with her! She just considerately left the lights out on her way through to the toilet, and thereby missed witnessing the crime. What Lisa assumed to be Anna’s groans of discomfort following a bout of self-induced puking earlier in the evening was really the killer stifling her screams. It’s excruciating to watch, in the best possible way. Rescue— or a chance of rescue, anyway— is standing right there as the psycho restrains Anna in her bed, but we already know there won’t be any escape for her. That scene alone was worth a star at rating time.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact