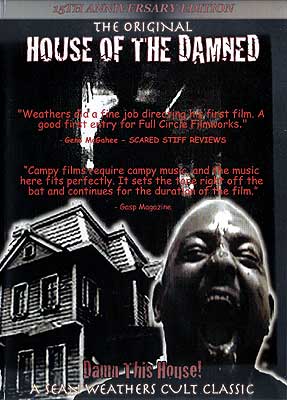

House of the Damned (1996) **

House of the Damned (1996) **

I don’t pay a lot of attention to the micro-budget indie scene. There’s just too much dross down there to make it worth my while. And that’s a shame, because there really are a lot of interesting filmmakers working that stratum of the industry, hidden among all the nitwits making zombie and slasher flicks on $20 and a half-formed idea— people with visions, perspectives, and sensibilities that don’t get reflected anywhere else. Unfortunately, the same economics that give such folks the freedom to follow their own paths also have a way of restricting their accomplishments at the same time. If you’re not spending any money, nobody’s going to stick their noses in to demand that you cater to the perceived tastes of a broader audience, but you’re also likely to remain stuck with untrained casts, commonplace settings, consumer-grade equipment, and production schedules that allow absolutely no margin for error. Sean Weathers is one micro-budget writer-director I’d like to see get a little more money to play with, because the underground isn’t doing him justice, and he seems like someone who could stand up to the suits and remain his own man. His first feature, House of the Damned, is for all practical purposes a black Evil Dead with the setting shifted to a Boston rowhouse. It suffers from all the usual woes of a film shot for pocket change on a camcorder from Circuit City, but it’s also tantalizingly full of moments when a glimmer of real ability pierces the fog of inadequate resources.

In a beaten-up old rowhouse on Dorchester Avenue, a sick old man (Johnny Black) is rambling to his son-in-law (Walter Romney, of Hookers in Revolt) about some 200-year-old African queen. The younger man has heard it before, and has no intention of listening now. That’s when a beautiful woman in a headscarf (Monica Williams) charges in with a claw hammer in her hand, and beats the son-in-law to death with it.

Three months later, we learn that Hammer Lady is named Emily, and that she’s the old guy’s daughter. That would make her also the dead guy’s wife. It’s interesting that she appears to have suffered no consequences for her crime. I mean, she lives with an eyewitness who seemed pretty broken up about the murder while it was happening— it’s not like the old man can’t tell the police where to find her! We also learn that Emily has a daughter of her own called Liz (Valerie Alexander), and that tomorrow is the girl’s 21st birthday. It scarcely seems possible that Emily could have offspring that age, since she looks like she’s got a few years to go yet before she sees 30 herself, but don’t worry— that’s a plot point in the making. For the moment, just do what all the other characters do: shrug yours shoulders and think, “Huh. I guess black really don’t crack.”

Milestone birthday or not, Liz is in no mood to celebrate. Although she doesn’t even suspect that her mom killed her dad, the unsolved murder leaves her nearly as unsettled as she’d probably be if she ever learned the truth. Liz also resents the speed with which Emily has gotten over the family tragedy and put the past behind her, especially since she’s put it so far behind her as to get a new boyfriend (Buddy Love, from Black Dynamite and Ace Jackson Is a Dead Man). But in the manner of unscrupulous parents, Emily is doing a pretty good job of convincing Liz that she’s the one who’s being unreasonable. That being so, Liz submits to the party her mother has organized on her behalf. The guest list includes Liz’s best friend, Stacy (Kendra Ware), a Kinsey-5 lesbian whose crush on her is obvious to everyone but Liz herself; Ben (Glenn “Illa” Skeete, whom Weathers would hire again for both Hookers in Revolt and Lust for Vengeance), an aspiring rapper who has a bad habit of bullying his friends; Ben’s mildly retarded brother, Kevin (Clinton Philbert); and Heather (Blue), a girl with stubby little dreadlocks and a nice rack where her personality ought to be.

The evening goes reasonably well until Grandpa summons Liz to his room to hear a strange story. It’s the same one her father wouldn’t let him finish on the night of his murder, but the girl has no way of knowing that. Grandpa’s yarn concerns an African queen named Emerald, who despite being a famous beauty was lethally insecure about her looks. Emerald insisted upon the execution of any woman in her domain whom she deemed pretty enough to rival her, and her husband the king, besotted with his young bride, did exactly as she bade. Obviously that was no way to run a kingdom, and it would only get worse as Emerald’s advancing age put more and more girls at or above her level. In the end, she herself saw that, and turned to the black arts for a more permanent solution. A witch conjured up demons who made Emerald the following bargain: she would have 21 years of agelessness, but only in return for the sacrifice of the child she just bore at midnight on her 21st birthday. The terms of the infernal contract could be renewed as often as the queen wished, but each new installment of 21 ageless years required the birth and sacrifice of a new child. Liz doesn’t understand what any of that has to do with her, but I’m sure you do. Emily is really Emerald, and Grandpa is not her father, but rather her son. (One assumes Emerald had two kids during that generation, so that Grandpa’s services on the altar of sacrifice were not needed.) Unfortunately for both of her surviving children, Emily walks in just as Grandpa is finishing his spiel, and she recognizes at last the danger the old man poses. Sending the rattled girl downstairs to rejoin the party, Emily waits until she’s out of earshot before garroting her increasingly troublesome son to death.

Now it might seem to you that Emily is likely to have some difficulty sacrificing Liz at midnight if the house is stuffed full of people who’d have reason to defend her. The immortal queen has an answer to that, though. In fact, she’s got it rigged so that Liz’s friends will actually facilitate the ritual bloodletting. When the kids begin their inevitable piecemeal migrations to the house’s several bedrooms, Emily starts killing them off in such a way that they become her personal zombie hit squad. Liz might be tough enough to stand up to her mother alone, but Mom plus five zombies (counting Grandpa, who is also due for re-animation) is another matter. There is, however, one thing Emily really hasn’t figured on. The ghost of her ex is watching over Liz, and from his vantage point in the spirit world, he can see the secret to defeating Emily. Hidden in the basement is the scroll on which Emerald’s sorceress inscribed the contract with Hell, and if Liz can read it aloud backwards before midnight, the demons will take Emily in sacrifice instead. It’s just a question of whether Liz can last long enough to act on her father’s trans-dimensional coaching.

One thing I greatly appreciated about House of the Damned is that it’s one of far too few genre movies I’ve seen in which blackness is just taken for granted, rather than being turned into some kind of gimmick. Although there are plenty of black cultural signifiers in evidence, Weathers treats them like they’re no big deal— and that, paradoxically, is kind of a big deal in itself. Watch House of the Damned in tandem with, say, Leprechaun in the Hood, and I think you’ll understand what I mean. Weathers has made an exploitation movie about black people without making a blaxploitation movie. I don’t think a white writer-director working within the above-ground cinema industry could have pulled that off; the temptation to exoticize the characters’ lives would have been too strong, whether because of the filmmaker’s own psychology and social background, or because of pressure from corner-office types who saw money to be made from courting the gawker and race-tourist audiences. “Diversity” has become something of a cheesy liberal buzzword over the last 20 years or so, but stuff like House of the Damned shows why nurturing a broad range of perspectives in pop culture matters, even when the pop culture in question is just a junky homemade knockoff of The Evil Dead.

That shouldn’t be taken to imply, however, that House of the Damned’s sole merit lies in being a movie that assumes it’s normal to be black. Although the monochrome cinematography was chosen mainly for the sake of having one fewer variable to control, it gives this movie a look that sets it apart from the rest of the shot-on-video pack, while subtly alluding— in a way that doesn’t directly invite unsustainable comparisons— to another anachronistic black-and-white debut feature, Night of the Living Dead. The absence of color also helps disguise what a piece of crap cinematographer Aswad Issa’s camcorder was. It’s just a pity it can’t also disguise the insufficiency of the light available inside the house where the movie was filmed. Otherwise, though, the house is exactly what the story called for in a shooting location. It’s cramped and tight and surprisingly twisty inside for a modest urban living space, and the filthy basement is a perfect setting for battling zombies over a witch’s spell-scroll. On a more technical note, the roof also happened to be laid out just right for faking a stunt fall that Weathers could never have staged for real in his circumstances. More importantly, Weathers and Issa understood even at this early phase of their careers how to unlock at least some of the visual potential in an environment that many novices in their position would have allowed to remain just a dumpy old house.

On the other hand, Weathers shows a lot less promise here as a writer than he does as a director. It’s not an uncommon condition among micro-budget auteurs. It doesn’t matter so much that the story is a confection of clichés, because Weathers comes at them from directions I don’t often see. Nor is it so bad that none of his characters seem like real people, because part of the appeal of spam-in-a-cabin (or in this case, spam-in-a-rowhouse) is that it demands very little in the way of depth or characterization. It’s usually enough to avoid making the protagonist and her associates do anything egregiously stupid, and Weathers mostly manages that here. The real trouble is the overwrought complexity of the supernatural goings on, which demands much closer attention to detail than Weathers seems to have given it. Emily’s implied reason for filling up the house with Liz’s friends never truly convinces. The issue of the witch’s scroll comes out of nowhere, and doesn’t fit comfortably with the supposed African setting of the back-story; it’s too Christian, too Medieval. And I can’t imagine any reason for Emily to eliminate her husband three whole months before the prescribed date for Liz’s sacrifice, or for her not to have eliminated her son about 42 years ago. I don’t want to come down too hard on this stuff, because some of these oddball details are what keeps House of the Damned interesting in spite of its well-worn subject matter, but that aspect of the script really needed some additional pondering before it was set down in final form.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact