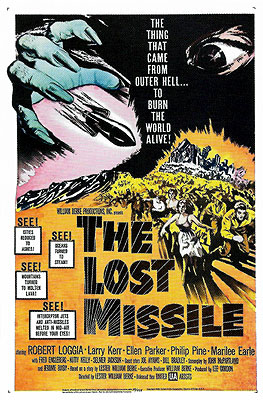

The Lost Missile (1958) **Ĺ

The Lost Missile (1958) **Ĺ

Conquering aliens and atomic bugs, conquering aliens and atomic bugsó oh, and also the occasional hunk of rock from the depths of space about to smack into the Earth like an enormous cosmic cue ball. It can be easy to form the impression that science fiction movies in the 1950ís never did anything else. So for all The Lost Missileís faults, this cheap, junky, and frequently boring film deserves kudos for a premise that I canít remember encountering in any previous sci-fi flick Although there are extraterrestrials involved, we never get to meet them, and the destruction they threaten to visit upon us is completely inadvertent. You might think of The Lost Missile as a disaster movie in which the disaster is a botched first contact with beings from another world.

You will recall that in 1958, both sides in the Cold War were scrambling to develop intercontinental ballistic missiles to augment and/or replace their fleets of manned bombers, and that both sides made closely guarded secrets of their progress in that direction. Itís perhaps understandable, then, that when the Soviet Unionís aerospace defense forces detect what appears to be a rocket of unknown design entering the atmosphere over their territory, they leap to the conclusion that theyíre seeing the initial volley of a nuclear strike from across the pole. Itís weird that the Capitalist-Imperialist Aggressors would launch but a single missile, though, and cooler heads are ultimately successful in mandating a proportionately limited response. Rather than immediately sending the Bears and Badgers aloft, the top generals order the mysterious projectile shot down. A surface-to-air missile scores a direct hit, but instead of destroying the target, it merely knocks it into a stable orbit at an altitude of approximately 26,000 feet. The SAM does seem to have done some damage, though, because waste heat from the craftís thermonuclear engines begins pouring out to the tune of a million degrees. Wherever the missile goes, the ground below is scoured clean to the now-molten bedrock in a swath five miles wide. At its current speed of over 4000 miles per hour, it should be passing into Alaskan airspace any minute now.

Meanwhile, at an applied sciences laboratory complex outside of New York City, Dr. David Loring (Robert Loggia, from The Ninth Configuration and Psycho II) heads up the Jove project, developing a nuclear-tipped antiaircraft missile to succeed the new Nike Hercules. (Postwar aerospace programs were so complex, and involved so much untried technology, that it was often necessary to begin working on next-generation systems before the equipment they were intended to replace had even entered service.) Itís a demanding, high-pressure job, and Loringís assistant, Joan Wood (Ellen Parker), ought to understand that better than anybody. But when it comes to the conflict between Davidís work schedule and her determination to get the bossís wedding ring onto her finger, Joan isnít understanding at all. Then itís ďYou love that hydrogen warhead more than you love me!Ē (Oh how I wish I were merely paraphrasing for effectÖ) Nor is Joan the only woman attached to the lab whoís had to reconcile herself to coming in second behind the groundbreaking new weapon. Loringís colleague, Dr. Joe Freed (Phillip Pine, of The Phantom from 10,000 Leagues and The Invasion of Carol Enders), is expecting a baby within the next day or two, but the chances of him getting time off to accompany his wife (Marilee Earle) and mother-in-law (The Mad Doctorís Kitty Kelly) to the hospital are virtually nil. And thatís before General Barr (Larry Kerr, from The Colossus of New York), the labís military liaison, arrives in a near-panic to place the whole complex under emergency lockdown.

Yeah, the radar stations in Alaska just noticed that weird-ass rocket. Loring and his fellow whitecoats swiftly reject any notion of such an advanced device being a new Soviet weapon, and a quick round of ambassadorial phone calls convinces the folks in Washington that the scientists are right; the Russians in particular are all, ďAre you kidding? We were afraid it was one of yours!Ē Since no one on Earth will claim responsibility for the deadly missile, that means no one is in a position to shut it down or to summon it back home, so the obvious answer is to destroy it before it reaches an inhabited area. Mind you, the Russians already determined that thatís easier said than done, and the interceptor pilots of Air Defense Command are about to discover that itís only gotten harder since the damaged machine started spewing stellar-grade heat all over the place. Air-to-air rockets meant to bring down Soviet bombers vaporize while still miles from their target, and fighter planes limited to transonic speed are unable to get out of the way when the alien missile comes streaking by at Mach 6. Nor do ground-launched Nikes fare any better. Meanwhile, the missileís course and speed will put it over Ottawa in a bit less than an hour, and over Manhattan seven minutes after that. Then its spiraling orbit will gradually carry it over the entire globe, cooking every square inch of the planetís surface, one five-mile strip at a time. There is, however, a single ray of hope in this bleak picture. The Jove airframe is designed to withstand unbelievably high temperatures; evidently the idea is to enable its operators to get off one last shot even from inside an atomic fireball. (The biggest strategic bombers of the 50ís could carry up to four nukes, so I suppose it just barely makes sense to want that capability.) Of course, itís already been established that Jove isnít finished yet. The prototype round is ready to fly, but Loring and his staff are still working on the warhead. Thereís a chance, though, that Jove could be quickly modified to take an off-the-shelf physics packageó from a Genie, say, or a Hercules. Even so, 63 minutes before New York goes up in flames is cutting it awfully close.

The most serious item in The Lost Missileís demerit column is all the goddamned stock footage. Granted, for military gear geeks like me, thereís a certain appeal in getting to see how the wingtip rocket pods on the F-89D worked, in close-up and slow motion (to cite just one example of the plane-porn delights available from this film), but weíre talking about a movie that is literally half stock footageó maybe even a bit more. No one should be expected to tolerate such enormities, not even the most dedicated aficionados of late first-generation jet fighters. Furthermore, that huge mass of recycled footage contains much that isnít even as interesting as an obscure old plane in flight. A lot of it takes the form of generic outdoor establishing shots, of crowd scenes that the producers were too cheap to populate themselves, of foot and road traffic standing in for the evacuation efforts in Ottawa and New York. Many viewers are apt to fall asleep long before The Lost Missile gets to the good part.

Others, meanwhile, will be driven away instead by the tawdry melodramas surrounding David and Joanís engagement on one side and the Freed coupleís baby on the other. No one will want to see Joan stridently and unreasonably demanding that her selection of the perfect wedding ring be assessed at greater significance than Davidís design efforts on the Jove project, but her bitching isnít half as irritating as his failure to recognize what a bullet he just dodged when she storms off and breaks up with him after being told that her indecision has wasted the lunch hour allotted for their quickie civil ceremony. The Freedsí subplot is easier to take, since Joe and Ella alike are more realistic about the lifestyle of a scientist doing cutting-edge engineering for the Defense Department, but itís still a lazy clichť. Itís just not clear at first whether weíll be looking at the ďnew life in the shadow of total annihilationĒ trope or the one about the guy whoíll never live to see the longed-for life change he was right about to get before the plot came down on him like a ton of gold retirement watches.

Do try to persevere, though, because there is a good part. As the film wears on, it becomes increasingly apparent that there isnít enough time. Loring wonít be able to modify the Jove prototype fast enough to save Ottawa, and once thatís on the table, the destruction of New York and indeed the rest of the world no longer seems out of the question. There was, after all, a small but important tradition of apocalyptic sci-fi movies in the 1950ís. It turns out that The Lost Missile isnít actually one of those, but the conclusion is remarkably downbeat nevertheless. In a stunning slap at the usual escapist audience for cheap sci-fi, it leaves one of the central characters dead of radiation poisoning and another permanently blind from the flash of the Jove missileís detonation. And responsibility for both of those tragedies can be laid at the feet of a gang of teenaged thugs who carjack the people in question on their way to the Jove project launching pad with the makeshift warhead! Itís not as powerful, mainly because nobody involved seems as much like a real person, but the ending of The Lost Missile plays almost like a less nihilistic foretaste of These Are the Damned.

And with the realization that the end of the world is a legitimately possible outcome here, there follow all sorts of reevaluations of what has come before. The muddy animated clips of the alien missile flying over this or that bit of countryside become progressively more disturbing as it sinks in that the aftermath of its passing is supposed to look like that, depicting a landscape not just marred, but destroyed beyond any possibility of recognition. The absence of communication between humans and aliens becomes retroactively meaningful, as it dawns on the audience that whatever crew, scientific instrumentation, or automated message for humanity the ship carried was destroyed when the Russians tried and failed to blow it out of the sky. And from there, it follows inexorably that this fictional apocalypse, like the real one looming over the Earth at the time The Lost Missile was made, is entirely the product of human mistrust and stupidity. Itís a pretty potent wrap-up for a film that spends most of the running time being Stock Footage: The Movie.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact