Immaculate (2024) ***

Immaculate (2024) ***

Last year, with The Pope’s Exorcist, we astonishingly got the next best thing to a 1970’s Italian Exorcist ripoff. This year, with Immaculate, we’re getting the next best thing to an Italian ripoff of Rosemary’s Baby— which might be even more exciting, because Italian Rosemary’s Baby clones never really existed back in the day. At most, there’d be a pilfered plot point or two shoehorned into some other model of occult horror flick, like when The Tempter’s possessed heroine starts trying to get herself knocked up for Satan, or when several characters become convinced that a woman is carrying the Antichrist’s baby in Holocaust 2000. What’s more, Immaculate combines the narrative framework of a religiously significant pregnancy with the unbridled anticlericalism of a 70’s Naughty Nun movie to create the exploitation horror film that today’s Roman Catholic Church truly deserves.

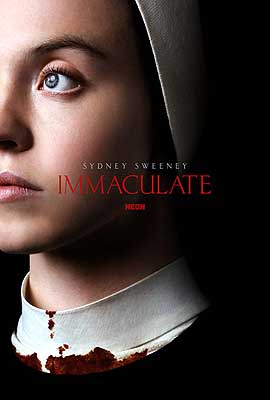

American novice nun Sister Cecilia (Sydney Sweeney, from Spiders and The Ward) is about to commit to the worst, most spiritually corrosive gig in all of women’s monasticism. Far from home, in the Italian countryside, she intends to take her vows at a convent that exists to provide hospice care for terminally ill old nuns, no small percentage of whom are afflicted with some form or degree of senile dementia. You might justly ask how she got it into her head to do such a thing; the sullen, angry nun charged with conducting Cecilia’s orientation certainly does. What it ultimately boils down to is that Cecilia has been struggling half her life to discover the purpose behind her survival of what ought to have been a fatal childhood accident. Surely God must have meant for her to do something with the second chance that He so improbably granted her after she was pulled from that frozen pond with sodden lungs and an unbeating heart? St. Stephen’s Convent seemed to offer the correct magnitude of spiritual challenge when it was described to her some months ago by its affiliated priest, Father Sal Tedeschi (Álvaro Morte), and so here she is, whether the longer-serving sisters like it or not.

We already know this is a horror movie, though, so obviously something nefarious must be afoot at St. Stephens. And we already know from a pre-title sequence that at some unspecified point in the past, another young nun tried to sneak out of the convent under cover of darkness, only to be caught at the outer gate by a gang of menacing sisters wearing featureless crimson masks, and buried alive for her transgression. No sooner has Cecilia taken her vows from the nunnery’s patron, Cardinal Franco Merola (Giorgio Colangeli), than she begins to see and hear disturbingly strange things. She has nightmares that seem to be trying to warn her of something. Birds take suicidal headers into windows while she’s gazing out of them. Somebody keeps sneaking around her bedroom while she sleeps, but the only prowler she ever catches is the Alzheimer’s-raddled Sister Francesca (Betti Pedrazzi, of Pantafa: The Breath-Stealing Witch, returning to territory she once trod as a young woman in Behind Convent Walls). Muffled voices cry out for help in the convent courtyard at night, but Cecilia never locates their source. And after the celebration thrown by Cardinal Merola to welcome her and all the other new sisters, Cecilia follows the sound of incoherent, anguished moaning to the convent chapel, and finds one of the crimson-masked nuns lying prostrate before the altar in a transport of religious ecstasy. Mother Superior (Dora Romano) happens along just then to explain (in a completely sane and normal way, I’m sure) that “suffering is love.” This she does while fondling (also in a completely sane and normal way) the most precious of St. Stephen’s holy relics, a purported nail from the True Cross.

Then one day, Ceclia gets sick. She and Sister Gwen (Benedetta Porcaroli), the one real friend she’s managed to make at the convent, are taking a bath together (but not, you know, taking a bath together— this isn’t that kind of nunsploitation movie) when Cecilia suddenly begins vomiting uncontrollably. Gwen and some other nuns rush her to the infirmary, where Dr. Gallo (Giampiero Judica) gets her stomach settled, and starts running tests. The ailing nun is wholly unprepared for what happens next, however. As soon as she’s feeling something like her old self again, she gets called into Cardinal Merola’s office, to be grilled by him, Tedeschi, and Mother Superior on the subject of her chastity! That’s understandable, though, when you realize that Sister Cecilia is pregnant. Normally that’s a bad look for a nun, but since Dr. Gallo’s examination could turn up no physical evidence beyond the pregnancy itself that the girl has ever had sex, it also becomes understandable that the convent authorities would want to hear what she has to say for herself before giving her the boot. Still, one can’t help noticing that Cecilia’s interrogators all seem downright eager not merely to believe her when she swears she’s a virgin, but to believe as well that her pregnancy is a divine miracle (rather than— I don’t know— deciding that the Devil has endowed her with a self-regenerating super-hymen or something). It’s almost as if they were expecting something like this to happen.

Cecilia won’t be learning the full story for a while yet, but as a matter of fact, they were. Father Tedeschi spent 20 years as a biologist before deciding that his true calling lay elsewhere, and when he came to St. Stephens, that background enabled him to fully appreciate something that had escaped all of his predecessors in his current post. That supposed nail from the True Cross? It has traces of dried blood and scraps of desiccated tissue adhering to it, so it very definitely was once used to crucify somebody. If the relic really is what it purports to be, then those residues are the literal flesh and blood of Jesus Christ, no transubstantiation necessary. And to someone with Tedeschi’s training, they’re also repositories for the DNA of Christ. In much the same way as Cecilia figures God must have saved her from drowning for a reason, the leaders of St. Stephen’s Convent consider it obviously meaningful that He sent a biologist-priest to the one religious institution in the world that has the Holy Chromosomes in its reliquary. It must be God’s will that they give the Second Coming a head start by impregnating one of the virgins under their authority with a test-tube savior! If Sister Cecilia is the sort of person that Tedeschi has taken her for, then she’ll perceive at once the uniquely sacred privilege being bestowed upon her. And if not, well… This is the Roman Catholic Church. When has the Roman Catholic Church ever given a single fuck about a woman’s plans for her own uterus?

This means very little in the grand scheme of things, but it bugs me, so I do want to address it just briefly: Immaculate has the wrong title, theologically speaking. When Roman Catholics speak of the Immaculate Conception, they’re talking about the conception of Mary, not Jesus; God impregnating Mary without de-virginizing her is a whole ’nother miracle. What makes Mary’s conception “immaculate” is that the sperm and ovum that made her each got a special, one-time-only “get out of Original Sin free” card from on high, so that her womb wouldn’t have Eve cooties all over it later, when God needed it to incubate His only begotten son. Wouldn’t want the savior of mankind to come out as some kind of spiritual flipper-baby, right?

Anyway, it took me a while to warm up to Immaculate. Throughout its first half, this movie is far too reliant not merely on blunt and clumsy jump scares, but on blunt and clumsy jump scares that come in the wrong order, and don’t mean anything. The pacing of those scares is annoying, too— so metronomically regular that you could almost resynch your laptop’s clock by them. Beyond that, there’s a counterproductive scattershot quality to the signs that something isn’t right at St. Stephen’s Convent. A lot of Cecilia’s weird experiences early on are threadbare commonplaces of the occult horror subgenre that get trotted out whenever somebody is about to get possessed by the Devil, or to bear his infernal offspring, or even just to buy a house where Beelzebub once clogged up the toilet after an ill-advised visit to Taco Hell. Others look like (and may indeed be intended as) encounters with the ghosts of Cecilia’s predecessors. But since the evil inhabiting the nunnery is purely human in nature and origin, these manifestations are at best a distraction and at worst a cheat. I take issue, too, with the crimson masks sometimes worn— but only during the first act— by the senior nuns who are in on Father Tedeschi’s Christ-cloning conspiracy. What ultimately makes this film so effective is that its villains are wholly and unshakably convinced that they’re the good guys. The last thing they should be doing is dressing up like a coven of Satanists from a mid-80’s speedmetal album cover!

Immaculate rights itself, however, at the exact moment when it reveals the full baroque outrageousness of its premise. I went into this movie assuming that the “Divine” miracle of Sister Cecilia’s virgin pregnancy would turn out to be a Satanic miracle instead. There’s absolutely no shortage of films on more or less that theme, after all, and this movie has been acting like one of them from the word go. But then Father Tedeschi takes her down to the basement to see his lab, and the astounding audacity of Immaculate comes completely into view: they’re trying to clone Jesus. The villains are trying to clone Jesus, so that they can implant him in the womb of an effectively captive nun. And what’s more, the filmmakers are rightly treating that as a violation every bit as appalling as a coven of witches conspiring to have Rosemary Woodhouse mother the Antichrist! When was the last time you saw anything approaching that level of bomb-throwing provocation in a theatrically-released horror film? The whole business becomes steadily more subversive the longer you think about it, too. Remember the opening chapter of the Gospel According to Luke? That angel never asks Mary if she wants to bear God’s child, does he? No, he just springs the plan on her as a fait accompli, and disappears back to Heaven. Mary, of course, is thrilled with the idea, but the fact remains that she has no say in it. Immaculate never says so in as many words, but it inescapably invites us to compare her situation with Cecilia’s, and challenges us to find any categorical difference. Nor does it ever back down from that implicit position, or soften its tone of righteous fury, no matter how extreme the measures necessary for Cecilia to reclaim her bodily autonomy become. When her enemies will stop at nothing to turn her into a passive broodmare against her will, can she afford to stop at anything to thwart them? All I can tell you is that it’s been quite a while since a movie had me cheering so hard for something unconscionable as Immaculate ultimately does, and even longer since one left me earnestly wrestling with the question of how unconscionable it really was under the circumstances.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact