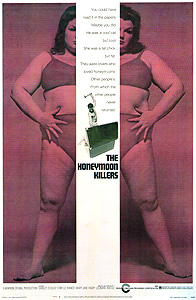

The Honeymoon Killers / The Lonely Hearts Killers (1969) **

The Honeymoon Killers / The Lonely Hearts Killers (1969) **

Growing up in the orbit of Baltimore and being the species of movie fan that I am, it is only natural that I be fairly well versed in the works of John Waters. I’ve never seen any of the really primeval stuff he made with Maelcum Soul, of course (if you weren’t around to catch Roman Candles and Eat Your Makeup during their initial screenings, you’re pretty much shit out of luck), but I’m fully caught up on the definitive Divine period, and I’ve endured enough of the films from the current Indie Darling era to know that I needn’t bother with the rest of them. I’ve also consumed as much of Waters’s writing as I could get my hands on, meaning that I’m acquainted with the director’s commendable habit of giving public props to the 60’s junk auteurs who inspired him in his youth. I’ve read his panegyrics to Herschell Gordon Lewis and William Castle (in fact, it was Waters who introduced me to Castle— for which he has my undying gratitude), his ardent expostulations on the likes of Beyond the Valley of the Dolls and Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, and thus it is that I’m somewhat taken aback to realize that I can’t remember him ever saying anything about The Honeymoon Killers. There is no way in hell that Waters did not see The Honeymoon Killers in his formative years, and precious little way in hell that he didn’t study it. Indeed, I can easily envision the young John Waters dragging the young Glen Milstead along with him to watch it repeatedly, offering it up as a short course in becoming truly Divine. This is exactly the sort of movie that Waters himself would have made as the late 60’s matured into the early 70’s, except that when Leonard Kastle spins this true-crime-inspired yarn about a put-upon fat girl temporarily making good by doing bad, he does it with a completely straight face.

Martha Beck (Shirley Stoler, whose career was otherwise mostly confined to small parts like those she played in A Real Young Girl and Frankenhooker) is the last person in the world who should work as a nurse. Sullen, short-tempered, and mean to the point of misanthropy, you have to wonder how she faces the thought of helping people for a living, day in and day out. She lives in a modest house with her nearly senile mother (Dortha Duckworth) and an only slightly less daffy older roommate by the name of Bunny (Blood Bath’s Doris Roberts), but it hardly seems a happy existence for any of the three women. Mom resents Bunny’s efforts to exert some manner of control over her escalating eccentricities, Bunny resents the constant attention that Mom requires in order to keep her out of trouble, and Martha seems never to have met a single thing that she didn’t resent. Both of the older ladies have noticed Martha’s eternally sour disposition, too, and one day, Bunny decides to try doing something about it. Without asking Martha’s permission, Bunny signs her up for a mail-order matchmaking service. Martha is horrified when her membership confirmation arrives (she thinks Bunny is being snide about her non-existent social life), but she starts to mellow out when she gets her first letter from a New York-based Spanish immigrant called Raymond Fernandez (Tony Lo Bianco, from God Told Me To and Sex Perils of Paulette). She writes back promptly, and before she knows it, she’s in the midst of a full-blown romance by mail. Eventually, she has Raymond over to visit for a few days, and they get along just as well in person as they do via the post office. In fact, Martha enjoys having Raymond around so much that she doesn’t want to let him go home. Raymond says he’d stay on longer if he could, but he’s expecting an important delivery, and it’s absolutely necessary that he be present to accept it. He’s an art dealer by trade, you see, and he’s expecting this particular piece of merchandise to make or break him for the next few months. Indeed, were it not for the rather large loan that Martha had generously extended him a few days ago, he would have had to leave yesterday. Wait— did he say Martha made him a loan? Doesn’t that sound kind of fishy to you, especially coming from a man who’s on his way to the train station to take his leave of the woman who fronted him the money in question?

Yes, good catch there. Raymond’s a gigolo, alright, and no sooner has he made his way back to New York than he composes a long and detailed letter to Martha, breaking off their relationship. But Raymond’s also a Spaniard, remember, and despite her lack of outwardly apparent experience with men, Martha knows just how to handle these wildly romantic Latin types. Martha has Bunny call Raymond on the phone, to pass along word that she’s in the midst of a nervous breakdown over him, and is threatening suicide. Naturally, Fernandez cannot resist the appeal of this grand, mad passion he has supposedly inspired, and he agrees to take Martha back. It’ll be a couple of years in coming, but this inglorious surrender to Latinate romantic machismo marks Raymond’s first step toward his own undoing.

I should point out that while all that was going on, Martha’s boss at the hospital got wind of her affair, and gave her the sack. We won’t be finding this out until the end (heaven knows there’s no indication of a period setting in the film itself), but this is 1947 we’re talking about, and apparently it was okay to fire nurses for pursuing insufficiently chaste private lives in those days. That means a dire and sudden need for money, and nowhere for Martha to turn except to Raymond. The only two points on which Fernandez will ever successfully assert himself over his new girlfriend now come in rapid succession, as he first refuses to take her in so long as she has her mother in tow, and then makes it clear that he has no intention of seeking anything that would normally pass muster as gainful employment. If Martha wants to move in with him, she’s going to have to put Mom in a nursing home, and accept that sponging off of insecure single gals with sizable nest-eggs is going to be the primary form of economic activity within their household. Martha grudgingly does as Raymond commands, after which Raymond Fernandez ceases to exist officially. Henceforth, Raymond will be “Charles Martin,” an American by birth who was raised by relatives in Spain from early childhood, and who now lives inseparably with his little sister, Martha. “Charles” continues to prowl the matchmaking services in search of exploitable women, and then he and Martha move in with them just long enough to separate them from their life savings. At Martha’s insistence, Raymond attempts to do this without actually marrying the women, let alone consummating the relationships, but sometimes the altar is the only crowbar strong enough to pry a lady away from her money. Even then, Martha is a cock-blocker par excellence, and as her performance on the telephone that day probably suggests, she possesses a vast arsenal of head-game techniques with which to keep Raymond in line should she ever suspect him of growing attached to one of his victims.

She’s also a lot more ruthless than even she probably realizes. Case in point: Raymond one day takes up with a Southern woman (The People Next Door’s Marilyn Chris) in need of some Quaker Instant Husbandtm to explain away an inconvenient pregnancy. Myrtle (as this brassy belle is called) claims to be through with men now, so in theory, Martha has nothing to worry about. But when Martha and “Charles” arrive at Myrtle’s house, the latter woman begins visibly thinking better of any intentions she may have had to start playing for the other team. It takes all of Martha’s talents to keep Myrtle away from her “brother,” even to the extent of insisting that she and Myrtle share a bed until the marriage is official. Myrtle, however, turns out to be quite the recreational pill-popper, opening up the opportunity for a more permanent solution to the problem. Martha gives her some drugs which she presumably stole from the hospital dispensary on her way out the door, and when the time comes to hit the road for the church (all concerned having decided that an out-of-town ceremony is strategically wise), Myrtle is painfully ill. Raymond puts her on the bus, anyway, saying that he and Martha will follow along in his car, but she’s dead in her seat by the time it pulls into the terminal at their supposed destination.

The poisoning of Myrtle Young establishes what will henceforth become the couple’s pattern. In addition to worming his way into lonely women’s hearts and absconding with all their cash, Raymond now starts leaving a trail of bodies behind him— although in each case, it’s the much more physically imposing Martha who does the actual killing. Next up is Janet Fay (Mary Jane Higby), 66 years old and nearly as soft in the head as Martha’s mother. She’s the biggest prize yet, worth fully $10,000, and it is Martha’s hope that Raymond’s winnings this time will enable him to retire from the gigolo business and make an honest woman of her. It sounds plausible enough, and Janet is certainly cooperative about converting everything she owns into portable (and stealable) form, but the old lady starts getting the feeling that something isn’t quite kosher once she’s finished signing all the checks and deposit slips. Awakening at about 2:00 am, she belatedly rejects “Charles’s” plan to spring the marriage on her relatives as an after-the-fact surprise, and starts demanding to use the telephone. Martha tries to talk her down, but it quickly escalates into a shouting match. The shouting match escalates in turn into a claw-hammer beat-down immediately thereafter. The need to split the scene fast cuts deeply into the size of the haul that the conspirators had hoped to obtain.

That brings us to Delphine Downing (Kip McArdle) of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Delphine is Martha’s least favorite target yet, for unlike the preceding women, she is young and pretty in addition to being well-off. She also has a daughter (Mary Breen), and Martha is, if anything, even less fond of children than she is of humans in general. Even so, it seems at first that Martha will be successful in enforcing her usual separation regime, but she’s kidding herself there. Delphine not only sleeps with “Charles,” but gets knocked up by him! She confesses this to Martha, hoping to apply a little sisterly leverage in expediting the planned marriage. That’s obviously the last thing Martha wants now, though, and the news inspires her to her cleverest and dirtiest trick yet. She channels her fury at being cheated on into a story about her brother refusing to consort with such loose women as Delphine has shown herself to be. There will be no marriage now, and there certainly won’t be any sticking around to care for the bastard baby. In desperation, Delphine agrees to take an abortifacient dose of an allergy medication that Martha carries with her. This, of course, is really the same poison that disposed of Myrtle Young, but Martha is just a little too slow in administering it. Ray comes home from an errand with Delphine’s daughter before the job is done, and all hell breaks loose. Raymond manages to get the little girl confined in the cellar long enough for Martha to finish with Delphine, and then it’s downstairs to drown the kid in the utility sink. An odd thing happens, though, while Martha is trading up from mere murder to infanticide. The shriveled little thing that passes for her conscience acts up at last, and the deadlier of the Honeymoon Killers places an anonymous phone call to the cops, turning herself and her boyfriend in.

The Honeymoon Killers was based on the exploits of Martha and Raymond’s real-life namesakes, and the movie is actually pretty close to the truth, as these things go. The real Beck and Fernandez met through a matchmaking service in 1947, and they conducted themselves in the financially predatory way to which the latter was accustomed until 1949, when they killed the real Janet Fay and the real Delphine and Rainelle Downing. They remained creepily devoted to each other throughout their arrest, trial, and terms of imprisonment, until they were executed at Sing Sing on March 8th, 1951. The main difference between the movie and what is known to be true is that it was neighbors who called the cops to report the Downing murders. The police who investigated the case suspected that there could have been as many as 17 other victims over the preceding two years, but could give the prosecution no firm case for any but the Fay and Downing killings. Another interesting detail that didn’t make it into the film concerns the criminals’ lives before they met each other. The real Martha Beck had two kids from a previous marriage, while the real Raymond Fernandez had four back in Europe.

I really wish The Honeymoon Killers wasn’t so goddamned dull, and I say that not merely because I can think of few uses of my time less edifying than sitting through boring movies. The spectacle of a classic John Waters premise played straight is too alluring, to say nothing of the prospect of a genuinely female Divine. The relationship between the two protagonists is equal parts Divine and David Lochary in Multiple Maniacs, and Divine and Tab Hunter in Polyester, and it’s impossible to watch Shirley Stoler’s performance without looking for hints of Glen Milstead peeking out through her. The weirdly sympathetic portrayal afforded to real-life serial killers also suggests Multiple Maniacs, in which Lady Divine and Mr. David were to have been the perpetrators of the Tate-LaBianca murders (still unsolved when shooting began), and is recalled again in Female Trouble, with its dedication to Manson family hatchet man Charles “Tex” Watson. The movie’s visual style even suggests the no-frills journeyman esthetic that Waters exhibited throughout the early years of his career. I’d like to be able to recommend this movie to fans as an unheralded probable influence, but what the hell kind of recommendation would “check this out— it’s really interesting from an academic perspective, but it’s also stultifying and mostly terrible” be?

That “mostly” is the other big reason why I wish The Honeymoon Killers had some more life to it, because this movie contains a handful of scenes that any grindhouse atrocity exhibition would be proud to call its own. Even though the act proper takes place offscreen, it’s impossible not to be horrified by the drowning of Rainelle Downing, and her mother’s death as she’s force-fed pills is no picnic either. But the jewel in The Honeymoon Killers’ crown (if it hadn’t pawned the crown to buy crystal meth) would be the whole sick sequence that begins when Janet Fay wakes up in the middle of the night to pester Martha with inconvenient questions, and concludes with the younger woman bashing the elder to death with a hammer. In its way, the brutal slaughter of the helpless elderly is no less a taboo subject than child-killing, and the movies in general have been even shier about depicting it than they have infanticide. A film that violates both unspoken interdicts ought to be one not to be missed.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact