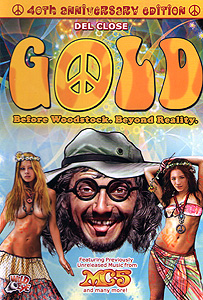

Gold (1968/1972) -*½

Gold (1968/1972) -*½

I was rather flummoxed when a screener copy of Gold showed up in my mailbox, and not merely because hippy movies are not something I habitually review. The packaging and the accompanying press release were extra-effusive, as if Gold were a long-lost classic that fans had spent decades clamoring for, and yet not only had I never heard of it, but I didn’t even know anybody who had— and the folks I keep in touch with cover just about the full spectrum of cinematic niche interests. Small wonder, that. It turns out that Gold never received an official domestic release at all, surfacing briefly and belatedly only in Britain before vanishing into obscurity for my entire lifetime and then some. It was obviously too freaky for the majors (both in the sense of being vastly, unrelentingly weird and in that of being aimed squarely and exclusively at freaks), but also too sleazy for the arthouse crowd and yet not half sleazy enough for the raincoaters. There was indeed a natural audience for Gold, but 1968 was still a little too early for the people who knew how to reach that audience to be on speaking terms with the people who could finance such an undertaking. So now I can see where Wild Eye Releasing is coming from. The unveiling, after more than 40 years, of a forgotten early example of for-hippies, by-hippies filmmaking does indeed seem worthy of a little promotional overkill, even if the movie in question is rather on the stinky side.

Captain Harold Jinks of the State Police (Garry Goodrow, from Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Prey) represents the Law; we know this because he opens the film by spending an annoyingly long time telling us so. Then he goes to meet an old buddy of his, politician Verbal Talkingham (Sam Ridges), to discuss some ideas he’s had of late. Jinks, like most conservatively inclined people in the late 1960’s (just ignore the fact that he’s costumed for the 1920’s instead), is very concerned about public morality, which he believes to be in sharp decline, especially among the younger generation. What exactly he means to do about that, and how exactly Talkingham (who, by the way, is costumed for the 1890’s) fits into those plans, is noticeably vague at this point. Gold’s script was improvised on the fly by the cast and crew around a very general concept dreamed up by producer/director Bob Levis, and it’s much too early in the film for that process to have yielded anything really solid yet. All we can say for sure at present is that the cop has some manner of campaign for office in mind, with Talkingham as the candidate and himself as the power behind the throne.

Meanwhile, a greasy-haired weirdo (costumed for the present day) by the name of Hawk (Del Close, of Beware! The Blob and The Blob) has come upon a large pile of manure out in the woods. Excitedly, he scoops some up, then hobbles back to town (wherever that is) as fast as his crutches will carry him. Bursting into an Old West saloon where guitar-strumming hippies and joke-telling beatniks entertain an audience of Gene Autry wannabes and nude girls with unwashed hair and unshaven armpits, Hawk loudly proclaims that he has found gold. ‘Cause, you know— wealth is bullshit. It’s, like, deep or something.

The next day, Talkingham and Jinks round up everyone in town to get them all organized for the gold rush. Yes, I know— lack of organization is precisely the unifying characteristic of rushes on things, but if you want either sense or plausibility, you have simply not come to the right movie. The townspeople all board a train that had been used by about two out of every five Westerns ever made, and set off for Them Thar Hills. Hawk misses the departure, but somehow manages to circle round ahead so as to leap onto the train from the top of a water tower. On crutches. Without a stuntman. It’s honestly pretty impressive. In doing so, however, he breaks one of the feed-water mains to the boiler, resulting in his first run-in with Captain Jinks. Then no sooner does the engineer get the train moving again than Jinks incites a squad of the US Army to attack it. There is literally no diegetic reason for this turn of events at all. The crew just happened to bump into a squad of soldiers out on maneuvers, and both sides agreed that some use simply must be made of the serendipitous encounter. Perhaps inevitably given those circumstances, the attack makes no impact on what passes for the story, and neither it nor Jinks’s role in it is ever mentioned again. What does impact future events is how Talkingham passes the time while the train is under repair. He sneaks off into the surrounding woods with a glamorous blonde girl whom the community will later crown Miss Gold Nugget (Caroline Parr) to get in on a little of that “free love” all the kids keep talking about. This is the first firm indication of where Verbal’s true loyalties lie, and a forecast of the schism to come between him and Captain Jinks.

Now because this is supposed to be a gold rush, you might anticipate that the townspeople would devote most of their energies once they got where they’re going to mining, prospecting, and the like— or to whatever the equivalent activities would be in a situation where the “gold” is really cowshit. That’s not what happens, though. In fact, the concept of gold disappears from Gold almost completely at this point, and the only person who will ever make reference to it again is Captain Jinks. Rather than set up an extraction industry of any kind in the wooded hills, the people whom Jinks and Talkingham led into the wilderness just get drunk, smoke pot, and roll around naked in any mudhole that presents itself. (I swear, what is it with hippies and mud?!?!) This drives Jinks crazy— to which I can readily relate, albeit for very different reasons— and he organizes a political convention for the sake of choosing someone to act as mayor for the relocated community. Surely putting somebody formally in charge would result in things finally getting done around here, right? Naturally, Jinks has Talkingham in mind for the job, but their Common Sense Party faces a challenge from LeRoy Acorn (Orville Schell), who runs on an extremely concise and populist “horse pucky” platform. Talkingham and Jinks are reduced to falsifying the vote and surreptitiously beating the crap out of Acorn while the crowd is distracted by Miss Gold Nugget’s tabletop striptease in order to capture the mayorship.

Even then, things do not go according to the captain’s liking, for Talkingham has no intention of governing as his puppet. Indeed, Talkingham has no intention of governing at all. However dishonestly he got the job, Verbal means to be the kind of mayor his constituents want, the kind who blows off the “duties” and “responsibilities” of his office in favor of getting drunk, getting high, and fucking hairy, muddy hippy chicks in public places. Jinks tries hard to straighten him out, but it’s no good. When Talkingham graduates from refusing to enforce his backer’s vision of the Law to advocating its formal abolition, Jinks shoots him, and uses a fraudulent hunt for the assassin as a pretext for police-state policies that ultimately incarcerate everybody but Hawk and Acorn (I’m not really sure how Jinks misses them, of all people) inside a chicken wire stockade— where they go right on drinking, smoking up, and rolling around naked in the mud in defiance of the captain’s increasingly apoplectic commands to desist. Then Verbal’s muddy, nude ghost appears to Hawk in a dream, entrusting him with leadership of the revolution. That apparently entails talking Acorn’s ear off about Mao Tse Tung and Che Guevara while pretending that all the cylindrical items in a nearby junk heap are artillery pieces. Eventually, though, the revolution does get properly underway via a bulldozer that Hawk (and, for that matter, the film crew) finds sitting unattended yet fully functional in the woods. Hawk bulldozes Jinks’s prison, and the captain is finally forced to join his former subjects skinny dipping in a muddy pond.

The main thing I can say in Gold’s favor is that it’s noticeably less awful than Gas-s-s-s. Roger Corman might have been sympathetic toward the counterculture by the time he made the latter film, but Bob Levis and company were part of it. The distinction matters, and for good and ill, Gold captures the hippy radical sensibility in a way that no outside observer’s movie ever could. You simply can’t fake that head-spinning mix of the passionately aware and the stunningly full of shit, that eagerness to poke excoriating fun at even one’s own most dearly held positions, that commitment to changing the world for the better just as soon as we finish this last doob, maaaannnn… Gold therefore acquires a layer of anthropological interest that is either missing from or muted in contemporary hippy films originating closer to the core of the industry, and I’m almost always willing to give art actually produced within a counterculture a try.

I’m also always willing to declare such art to be crap, though, when that verdict is warranted, and Gold for the most part is unmistakably crap. Seriously, if you make a movie called Gold, and then use a Wild West gold rush premise to set up the story, don’t you think gold should have something to do with said tale? And considering the crass sight gag that launches the whole business— Hawk’s “gold” is just a great, big cowflop— maintaining touch with the ostensible premise would have offered just as much opportunity for calculatedly offensive absurdism as merely wandering wherever the next hit from the Muse’s bong led. Think of it: hippies dressed up like 49ers panning for turds; black-hatted bandits stealing sacks of shit from stagecoaches at gunpoint; Jinks and Talkingham negotiating with a city-slicker bank representative over the vault deposit of half a ton of manure… Funny or not, the jokes practically write themselves. But instead what bills itself as the organizing theme of the movie gets dropped almost immediately in favor of Captain Jinks’s tireless yet futile crusade against public nudity. Better to have called the film Public Morals— or if that sounded too cerebral, then Boobs.

Of course, even the captain’s efforts to make sure everybody else stays as sexually repressed as he is impose only the flimsiest of structures on Gold. More than anything, what this movie accomplishes is to demonstrate why improv acts don’t generally go on uninterrupted for 90 minutes: because it doesn’t fucking work. Del Close and Garry Goodrow were improvisational comedians of considerable standing in 1968; Close in particular would be idolized by seemingly everybody of consequence in the sketch comedy business for the next 30 years. They and a few of the other cast-members do manage the odd witty bit, as when Jinks introduces Talkingham as a man with “the bravery of Harding, the warmth of Coolidge, the sincerity of Bismarck, the eloquence of Dulles, the humility of Teddy Roosevelt, and the farsightedness of Herbert Hoover” right before his speech at the convention. There isn’t enough here for them to work with, though. An hour and a half is just too much time to fill when you’re making it up as you go along.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact