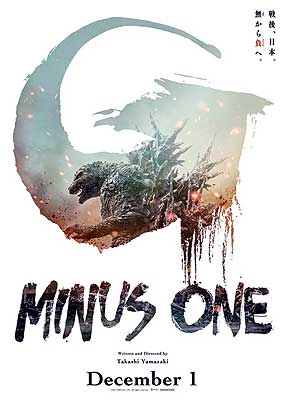

Godzilla: Minus One/Gojira –1.0 (2023) ****

Godzilla: Minus One/Gojira –1.0 (2023) ****

I was one of the hundred or so weirdoes who didn’t go see Oppenheimer last summer. I know plenty of people who did, however, and a criticism I heard from several of them was that the movie omitted (or erased, if you prefer) the perspective of the people actually subjected to the titular scientist’s handiwork. I leave it to others to address the merits of that argument directly, but I will say that I’m not sure I want Hollywood to try telling that side of the story. That’s because I don’t believe Hollywood knows that side of the story. Maybe no American does, except for the handful of US citizens of Japanese extraction (most of them students at the time) who had the foul luck to be in Hiroshima or Nagasaki on those days in August of 1945. Indeed, the mere fact that most of us think of the atomic bombings as a story separate from the fourteen months of conventional and incendiary air raids against Japanese cities that led up to them, or from the campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare that destroyed some three quarters of the merchant shipping that the Japanese people depended on for food and fuel, shows how little we grasp the experience of our former adversaries. So for those of you who felt like Christopher Nolan denied you an opportunity to sit in the corner for a while thinking about what your grandparents and great-grandparents did, permit me to recommend Godzilla: Minus One. That isn’t this film’s actual purpose, of course. Godzilla: Minus One was made to grapple with Japanese feelings of guilt, shame, and lingering anxiety as the defeated aggressors in the Pacific War. It was made to interrogate the paternalism of Japanese governments, and the Japanese people’s acquiescence to that paternalism, both in the Imperial era and, by allegorical extension, today. And although I’m less certain of this, I suspect it was made as well to encourage a more conscious and careful accounting of what present-day Japan stands to lose in its slow but steady drift away from the constitutionally-mandated pacifism of the postwar 20th century. But because Godzilla: Minus One looks at all those things from amidst the apocalyptic ash-heap to which the nation had been reduced by the end of World War II, it incidentally has some things to show the descendants of those who did the reducing, too.

It’s the summer of 1945, and any fool can see that Japan has lost its part of the Second World War. The conclave of military fanatics who’ve been ruling the country since the early 1930’s have a very idiosyncratic understanding of the implications, however, and as the noose of Allied forces tightens around the Japanese Home Islands, the governing generals think increasingly in terms of leading their people in a sort of national seppuku. The most conspicuous expression of that idea is the kamikaze program, already underway for more than a year, in which half-trained pilots crash whatever aircraft can be scrounged up into enemy warships, but every branch of the imperial military has gone all-in on suicide attacks of one sort or another. Meanwhile, the empire’s propagandists work to instill a similar spirit on the home front, exhorting the Japanese people to resist the coming invasion to the last drop of blood.

Not everyone is thrilled about dying for the emperor, however, even among those most thoroughly conditioned to do exactly that. Take, for example, a kamikaze pilot named Ensign Koichi Shikishima (The Great Yokai War’s Ryunosuke Kamiki, whom we last saw as the mo-cap model for the Child Monster in Big Man Japan). When the big day comes for him, Shikishima loses his nerve, pleads engine trouble, and diverts course to Odo Island, a remote speck of land in the Western Pacific where the Imperial Japanese Navy has established a service station for kamikazes. Mind you, chief mechanic Sosaku Tachibana (Munetaka Aoki, of Battle Royale II and The Snow Woman) sees through the pilot’s ruse immediately, but he’s more than happy to bullshit up a supporting cover story if it comes to that. Dying for a cause is one thing, but dying for a lost cause is just fucking stupid. Shikishima and Tachibana will soon have more pressing concerns than the pilot’s dereliction of duty, however, for Odo is home to more than a small garrison of Japanese soldiers and a few thousand technologically backward natives. The islanders say that the deep waters off their coasts are home to something called “Godzilla,” and although no sense of what that’s supposed to be has yet made it across the language barrier to the troops, the latter are about to meet Godzilla face to face. On the very night after Shikishima’s arrival, an immense, reptilian creature looking something like an amalgam of all the known megatheropod dinosaurs, but more than twice the size of even the biggest of them, wades ashore just beyond the perimeter of the IJN repair base. Thinking quickly, Tachibana realizes that the only weapons on the island likely to make an impression on such a beast are the 20mm machine cannons mounted in the wing-roots of Shikishima’s plane. At the mechanic’s command, Shikishima sneaks into his cockpit, waits for Godzilla to pass in front of him… and then completely freezes up, understandably terrified of what might happen should the monster prove even tougher than it looks. One of the men from the garrison panics when it becomes obvious that the pilot isn’t going to shoot, and opens fire with his rifle. Godzilla, unharmed but extremely annoyed by small-arms fire, goes berserk. By the time the creature’s fury is spent, only Shikishima and Tachibana remain alive to be picked up for repatriation to Japan at the war’s end some weeks later.

Shikishima comes home to a nightmarish wasteland. Nothing remains of Tokyo save block after endless block of burned-out ruins. Everyone he knew before shipping out— his parents, his friends, his schoolmates and coworkers— is dead, except for one middle-aged neighbor lady named Sumiko Ota (Sakura Ando, from Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura and The Great Yokai War: Guardians). Koichi is the only person still alive whom Sumiko knows, too, but don’t expect that to make them friends. He, after all, wasn’t supposed to come back from the war, so his return is, all by itself, testimony to his cowardice, and makes him a convenient scapegoat toward whom Sumiko can vent all her feelings of betrayal, outrage, and loss. But then, while exploring the makeshift bazaar that has sprung up in what used to be the nearest town square, Shikishima encounters a girl (Minami Hamabe) fleeing frantically from the consequences of who knows what desperate action. She literally crashes into Koichi, and thrusts the baby she was carrying into his hands before vanishing into the surrounding crowd. When the pair meet again after the girl has deemed the coast sufficiently clear to return to the bazaar, she introduces herself as Noriko Oishi, and moves herself and the infant into the ruins of Shikishima’s house, essentially daring him to evict them. He can no more do that than Noriko herself could abandon baby Akiko when she found her beside her dying parents some days ago, and the next thing Koichi knows, their mutual plight has forged the three of them into the next best thing to a family. Even Sumiko gets involved, despite her vociferous claims to be done with caring about anybody but herself, when she realizes that the kids next door don’t have a single clue between them how to look after an infant.

Paying jobs are scarce in a city made of cinders, but Shikishima finds work in one of the few growth industries that Japan currently has, clearing the surrounding seaways of the tens of thousands of mines laid during the war by the Japanese and Allied navies. In practice, that means going out just after dawn each morning with three other men— former merchant mariner Yoji Akitsu (Kuranosuke Sasaki), former military engineer Kenji “Doc” Noda (Hidetaka Yoshioka, from Village of Eight Gravestones), and former high school student Shiro “Kid” Mizushima (Yuki Yamada)— aboard a shockingly small and flimsy wooden boat to hunt up the deadly devices. Then once they’ve found a clutch of mines, the sweepers cut their mooring lines to make them bob to the surface, and blow them up with a 13mm machine gun scavenged from a navy arsenal somewhere. It’s hazardous work, naturally, but the wages are correspondingly good, and the gig comes with a substantial signing bonus. Job security is solid, too, considering how many years it’s likely to take to scrub the all the seaward approaches to Japan of mines. Koichi and Noriko thus get a real head start on rebuilding their lives, even as the country proceeds more fitfully and painfully on its own, much larger, reconstruction.

Then, in July of 1946, the United States conducts Operation Crossroads, the experimental immolation of 92 surplus military vessels in the lagoon of Bikini Atoll by two atomic bombs of the type that destroyed Nagasaki. At first glance, that doesn’t seem to have much to do with Shikishima, his found family, or indeed the citizens of war-ravaged Tokyo in general. But for the purposes of this movie, the Marshall Archipelago (of which Bikini is one of the more outlying constituents) is near enough to Odo Island that Godzilla has been known to visit from time to time. He’s in the Bikini lagoon on July 25th, and gets caught in the detonation of Test Shot Baker, the second, underwater explosion. The bomb has exactly the same effect on Godzilla as The Amazing Colossal Man’s test nuke has on Lieutenant Colonel Glenn Manning: although he’s grievously injured by the blast, the attendant radiation mutates the monster so that he not only heals those wounds with uncanny speed, but also begins growing and growing and growing…

Over the course of the next year, the stretch of Pacific Ocean between the Marshall Islands and Japan becomes a very dangerous place to sail. Many of the ships lost there during that time are sunk outright, but others remain afloat long enough to be discovered, revealing a kind of damage that no normal weapon should be able to produce. The wrecks look as if they’d been savaged by some impossibly huge animal rather than shot up, bombed, torpedoed, or burned. Eventually survivors of the sticken vessels are rescued as well, and their testimony consistently confirms that the thing destroying ships in the Western Pacific is a living creature of some species never seen before. A plot of the attack sites, meanwhile, indicates that the creature in question is headed in the general direction of the Japanese Home Islands.

That leaves Japan in a serious fix, even by kaiju eiga standards. Devastated by war and all but disarmed by its conquerors, the country is in no position to defend itself militarily, even assuming that conventional weapons would suffice to destroy the oncoming monster. And as if that weren’t bad enough, the United States is leery of deploying its own navy on such a fantastical-sounding mission; Josef Stalin would almost certainly assume that such a concentration of force within striking range of Vladivostok was actually directed against the Soviet Union. Douglas MacArthur’s occupation government therefore offers the following concession: the heavy cruiser Takao— the last major unit of the emperor’s once-mighty fleet that remains seaworthy— will be diverted from its voyage to the breaker’s yard in Thailand and recalled home until such time as Godzilla has been neutralized. Surely a ship that was designed to ambush aircraft carriers while their bombers were away on business can handle a sea serpent, right? And in the meantime, all those minesweepers scouring the seas for troublesome explosives can act as a picket line to track Godzilla’s movements, and maybe even get a couple hits in along the way. Shikishima, in other words, is on course for a potentially redemptive rematch with the monster he was too chicken to take a shot at on Odo Island, whether he wants one or not.

The Showa Godzilla movies, made between 1954 and 1975, collectively form a loose but nevertheless discernable overarching storyline. The Heisei films, made between 1984 and 1995, are in tight continuity (or at least an attempt at tight continuity) with each other, but reject the canonicity of all the Showa entries after the first one. And the Millennium sub-series, made between 1999 and 2004, abandons inter-episode continuity almost completely, with each movie apart from Tokyo S.O.S. (which takes up where Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla leaves off) serving as a direct sequel to the original Godzilla. Well, evidently we’re now in yet a fourth era of Toho Godzilla films, in which each new installment starts completely fresh, positing its own unique version of the monster, set in its own unique timeline where no such creature has ever been seen before. Furthermore, it looks like each of these new Godzillas will be designed to embody its own unique set of thematic concerns, carefully constructed in deliberate counterpoint to the ever-shallower spectacle that Legendary Pictures has made of the character on this side of the Pacific. Thus Hideaki Anno’s Godzilla: Resurgence reimagined the titular monster as a mindless but constantly evolving menace symbolic of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, in the context of a satire on Japanese culture’s hypertrophied regard for hierarchy and institutional formalism. And thus Takashi Yamazaki now gives us something that might be even stranger, an overtly allegorical Godzilla movie in which Godzilla himself represents nothing in particular beyond catastrophe in the broadest and most variable sense. Godzilla: Minus One directly acknowledges something that’s been true since the 1960’s, but hasn’t really been consciously exploited until the past decade or so: Godzilla, like any monster, can be modified to mean whatever we need him to mean.

That, in a roundabout way, brings me to this movie’s enigmatic title. As is often the case in Japanese media, there seem to be at least two distinct layers of significance in play. On the one hand, Godzilla: Minus One can be taken as a riff on the modern Japanese convention of using “part zero” to designate prequels, as in “Macross Zero” or Ring 0: Birthday. Although it isn’t strictly a prequel, Godzilla: Minus One does push the series timeline backward about as far as it’s possible to go without rendering the monster’s origin totally unrecognizable— to a phase even earlier than what “part zero” normally implies. But more importantly, the title hints at the threat that this new, even older, Godzilla poses to a nation already reduced to zero by the ravages of war. By introducing Godzilla at the very beginning of Japan’s postwar reconstruction, Yamazaki envisions a force that could end the nation’s transformation from militaristic, authoritarian empire to pacifist, consumerist liberal democracy before it is even properly underway. But in the spirit that every crisis is also an opportunity, he simultaneously imagines how facing down such a threat at so pivotal a juncture in history could have made the transformation still more fundamental, breaking the Japanese people once and for all of the social and psychological habits that come from being subjects rather than citizens.

With that as his objective, it’s apt that Yamazaki has given us not so much a remake of Godzilla: King of the Monsters as a parallel-universe version of it. Godzilla: Minus One’s viewpoint characters are not well-connected scientists and journalists, but just ordinary people trying to survive under extremely adverse conditions. It features surprisingly little battling against the monster in the usual sense, either, despite having clear structural and conceptual analogues for the original Godzilla’s depth charge offensive, fortification of Tokyo, and Oxygen Destroyer suicide mission. Fittingly, Minus One’s most dramatic confrontation between humans and monster doesn’t follow the kaiju eiga playbook at all, but is rather an homage to the climax of Jaws. (Shikishima and his minesweeping crewmates discover that they will indeed need a much bigger boat— although the boat in question doesn’t fare any better against Godzilla once it arrives on the scene!)

But where Yamazaki really enters new territory here is by rejecting the entire concept of heroic self-sacrifice, and by making that rejection a central theme of the film. This first comes up when Tachibana voices his approval of Shikishima shirking his responsibilities as a kamikaze pilot. The navy mechanic has it in hard for Shikishima when he re-enters the story in the third act, mind you, but he still doesn’t care that the pilot went all Bartleby the Scrivener on their superiors when commanded to blow himself up for the homeland. Rather, what drives the wedge between the ex-servicemen is Koichi’s true act of cowardice: his failure to fire on Godzilla when the monster was still merely an animal, and might indeed have been felled by weapons fit to destroy an airplane. Yamazaki is out to trick us, though. He encourages us at first to think that Tachibana, upon his return, has changed his mind about what Shikishima should have done two years earlier. But cannily, Yamazaki effects that encouragement merely by showing us the two men’s interactions strictly from Koichi’s point of view, after spending the bulk of the film up to then dwelling on the Shikishima’s assessment of himself as a coward and a failure. He counts on us to assume that the only way for Koichi to expiate such guilt would be to press home against Godzilla the kamikaze attack that he never made against the US Navy. After all, isn’t that what the original Godzilla’s Dr. Serizawa would have done in his place?

In fact, though, Shikishima is completely alone among the characters in imagining that any such thing is warranted. When the attenuated military response to Godzilla permitted by the occupation government inevitably fails, Doc Noda pulls whatever strings remain to him as an ex-military engineer to secure a leading role in developing a backup plan to be executed by a sort of anti-kaiju co-op recruited from among the citizens of Tokyo. And when he presents his proposal at a plausibly low-budget version of the official conferences and hearings that show up so often in Japanese monster movies, Noda is adamant that the trap he proposes to lay for the monster needn’t entail the sacrifice of anyone’s life, however many lives might be risked in springing it. It’s a subtle distinction, but a vital one. What’s more, Doc refuses to compel anyone’s participation, no matter how necessary their particular skills, resources, or talents might be to the undertaking, nor does he call for volunteers until after he’s at least sketched out the shape of his plan. Secrecy, coercion, and the profligate expenditure of human life— those, Yamazaki asserts, are the ways of the old Japan. It will be a new Japan that faces Godzilla, and if it survives, it’ll do things differently going forward.

That’s a lot to put on a monster movie, obviously, but Godzilla: Minus One carries the burden as ably as Godzilla: King of the Monsters bore its comparably heavy thematic load 69 years earlier. Although he’s made plenty of sci-fi and fantasy movies in his time, Yamazaki comes across as a dramatist at heart, and that sensibility serves him very well here. His portrayal of life during the earliest phase of Japan’s postwar reconstruction yields easily the most engrossing human story in any kaiju eiga of my acquaintance, which in turn imparts real-world weight to the monster action. The precarity of Koichi and Noriko’s life together creates an acute sense of what will be lost if Godzilla isn’t stopped, just as Shikishima’s shell-shocked inability to invest himself emotionally in that life the way it deserves conveys the severity of the losses he’s already suffered as a result of the war. Shikishima’s wounded psyche also becomes a microcosm for everything that the Japanese people must put behind them, both in order to rebuild their land and in order to overcome Godzilla— not merely in the expected metaphorical sense, but in a literal one, too, as it grows ever clearer that Noda will need the ex-pilot for his monster trap. (Note, by the way, that the character’s very name hints at how this subtext crystallizes into text. Koichi means “child number one,” while Shikishima— literally “scattered islands”— is a poetic name for Japan itself.) For such a young actor, Ryunosuke Kamiki puts up a very convincing show of having crammed a lifetime quota of suffering into just four years.

Meanwhile, on Godzilla’s side of the film, we have a curious paradox. In some respects, this version of the monster is noticeably weaker than what we’re accustomed to— as he needs to be if anything our heroes might be able to throw at him is to have any credible chance of bringing him down. Crucially, Yamazaki’s Godzilla is not invulnerable to conventional weapons. It’s just that he heals so rapidly that even ten 8” naval cannons can’t deal enough damage to outpace his regeneration. Also, Godzilla’s atomic breath is no longer a power that he can use at will. Not only does it take some considerable while to charge up, but every discharge leaves the monster visibly injured and temporarily weakened. On the other hand, when Yamazaki says “atomic breath,” he means atomic breath! Rather than working like the variation on dragon fire familiar from most Godzilla movies, or even like the devastating cutting beam seen in Godzilla: Resurgence, the Minus One Godzilla’s breath detonates when it reaches a certain range, with effects comparable to a ten- or twenty-kiloton A-bomb. It even produces fallout in the form of horrid black rain that no doubt markedly shortens the life expectancy of anyone exposed to it. So although he may not be as tough as previous interpretations, Yamazaki’s Godzilla is capable of destroying with a suddenness and finality that we’ve never seen before.

What’s more, all of this is presented with a level of special effects artistry that is similarly new to the Japanese side of the franchise. Indeed, on the technical front, Godzilla: Minus One equals or exceeds the American Godzilla movies, even the cheapest of which cost more than ten times the $15 million that Toho reportedly spent on this outing! Assuming that figure is a remotely honest reckoning of Minus One’s bottom line, I have simply no idea how the Shirogumi VFX shop pulled it off. The upshot, in any case, is that this movie is as immersive visually as it is psychologically. It is the total fucking package, comfortably exceeding every Godzilla film since the original, and offering even it stiff competition for the franchise championship. If you have any interest at all in kaiju eiga, you owe it to yourself to give Godzilla: Minus One a look.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact