Felicity (1978) **

Felicity (1978) **

For most of the 1970’s, raunchy comedies were the dominant mode of Australian sexploitation cinema. I’ll get around to those one of these days, but right now we’re going to talk about something altogether different. John D. Lamond, you see, didn’t like to operate in dominant modes. Rather, his approach was to look for the kinds of movies that other people (or at any rate, other people in Australia) weren’t making, so that his films would face as little direct competition as possible. In 1975, when Lamond decided to expand beyond the distribution and advertising realms of the movie business to become an independent producer/director, he started by making, of all things, a Mondo throwback called Australia After Dark, smuttily exoticizing his own country the way the Italians had exoticized foreign lands. Then with The ABC of Love and Sex, Australia Style, he created probably the closest thing to a German Aufklärungsfilm ever to emerge from the English-speaking world. Felicity, Lamond’s first fully narrative motion picture, and the biggest international hit of his career, aped yet a third strain of European sexploitation. As those well versed in 70’s soft smut will surmise from the title alone, Felicity is Emmanuelle’s Aussie foster daughter, although it also exhibits some influence from an older and now more obscure bit of celluloid scandal-bait, The World of Suzie Wong. Alas, Lamond didn’t really have what it takes to do one of these right, but the specific nature of its failures makes Felicity more interesting than most Emmanuelle copies that miss the mark.

Seventeen-year-old Felicity Robinson (25-year-old Glory Annen, from Spaced Out and Alien Prey, faking adolescence more convincingly than many actresses her age) is a student at the Willows End Ladies’ College, a convent school in one of Australia’s more verdant regions. She enjoys reading erotic literature, taking long and sensuous showers, skinny dipping in the lake just off school property, and being objectified by peeping toms of every description. Sometimes, if all the other girls in their dormitory are sleeping soundly, she also likes sneaking into bed with her best friend, Jenny (Jody Hanson, whose true age in 1978 I’m frankly content not to know). One day, Felicity receives a letter from Christine (Marilyn Rodgers, of Patrick and The ABC of Love and Sex, Australia Style), a family friend living in Hong Kong. She has arranged with Felicity’s parents for the girl to fly out and spend the summer with her and her husband, Stephen (Gordon Charles). Jenny is very sad to see Felicity go, but Felicity herself is bursting with excitement over the prospect of such an adventure.

The milestones of Felicity’s sojourn in Hong Kong bear a remarkable and explicitly non-coincidental resemblance to those of Emmanuelle’s sojourn in Bangkok. (Seriously, Felicity is reading the Mile High Club chapter of the Emmanuelle source novel when she realizes that the couple in the seat behind her are going at it. Hard to draw much bolder a line under a quotation than that!) That said, those milestones come in somewhat different form and order here, consonant with Felicity’s more conventional understanding of sexual awakening. The tryst with an arrogant boor (David Bradshaw, of Fortress— the one about the schoolteacher and her class taking on a band of masked maniacs, not the one about the futuristic prison) comes near the beginning of the girl’s journey, and serves to teach her that looks, money, and popularity with women are all lousy predictors of a man’s skill and attentiveness in the bedroom. The female mentor (the Indo-Scottish Joni Flynn, unconvincingly cast here as Chinese) who initiates Felicity into the world of strip clubs, massage parlors, and brothel barges, is older than her, and has secrets unrelated to her familiarity with the Hong Kong sex trade. And the person who steals Felicity’s heart, only to run off someplace where she can’t, or at least shouldn’t, follow is a man.

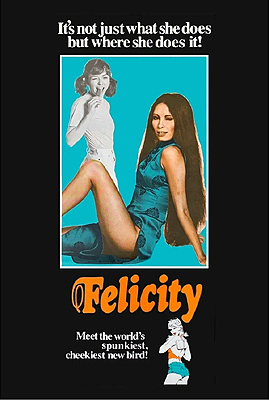

The fellow’s name is Miles (Chris Milne, from Thirst and The Day After Halloween), and he’s a freelance “adventure photographer.” Basically, he goes to hard-to-reach places, takes lots of pictures, and sells them to magazines like Time Out and Condé Nast Traveler. He and Felicity meet when he rescues her from being mugged or worse by a band of ruffians after an all-nighter in the red light district. The pair fall hard for each other over the ensuing week or so, which they spend living up to the movie’s original advertising tagline: “It’s not just what she does, but where she does it!” But can True Love really arise under such circumstances as these? And can it survive when the participants have such obviously incompatible arrays of other things to do and other places to be looming up in the all-too-near future?

Fair warning about Felicity: this movie has an all-timer earworm of a theme song, right up there with the ones from Julia and The Young Playmates. Worse yet, it plays not only over both sets of credits, but also over each of the film’s unconscionably numerous romantic montages. Be prepared to have the awful, syrupy thing stuck in your head for weeks.

I don’t think we’d watched more than the first half-hour of Felicity before Juniper pinned down exactly what was amiss with it. She called it the JC Penney version of Emmanuelle, which was right on so many levels. From a simple material perspective, it’s obvious that this movie is trying to simulate high-end style at a steep discount. John D. Lamond liked to quip that he made his early skin flicks on G-string budgets, and although Lamond’s skill at economizing is such that Felicity never looks nearly as cheap as it was, there’s nevertheless no disguising that Just Jaeckin had a lot more to work with. The film falls short of Mediterranean softcore standards in ways that money can’t directly account for, too. While even the junkiest French or Italian picture of this genre and era can be counted on to feature actresses ranging from beautiful to stunning, Felicity mostly gets by on the merely cute or good-looking, with only Glory Annen rising all the way to pretty. (In fairness, Felicity does compensate somewhat for that shortcoming by steering well clear of the “Yeah, but the men!” problem that bedevils Italian soft porn in particular. Chris Milne and Gordon Charles are both easy enough on the eyes, and David Bradshaw would be were it not for that Jack Taylor-ass moustache.) Most of all, though, Felicity feels JC Penney due to the all-pervasive conventionality of its take on libertinism. This is not the kind of movie in which anybody fancies themselves an intellectual heir to the Marquis de Sade, or posits eroticism as a revolutionary force. And even its darkest depictions of sexual exploitation have a banal consumerist vibe untouched by the spirit of true decadence. Until she meets Miles, Felicity’s Hong Kong adventure is mere sex tourism— and after they meet, we’re in straightforward youth romance territory, except with more exhibitionism. There’s nothing wrong with any of that per se, but it sits uncomfortably beside Felicity’s repeated invocations of Emmanuelle, The Story of O, and Erica Jong. And there absolutely is something wrong with casting a skin flick with people who have no idea how to act a sex scene, no matter how low their inhibitions regarding simple nudity. All in all, I’m not convinced that Lamond or his collaborators understood any of the things they were trying to emulate here.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact