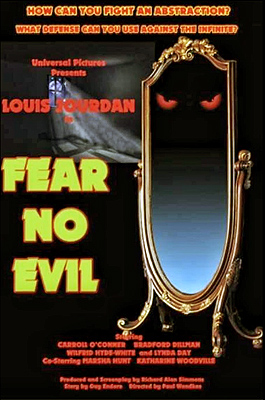

Fear No Evil (1969) ***

Fear No Evil (1969) ***

The rise of television as a mass medium couldn’t have come at a worse time, so far as Hollywood was concerned. Already reeling from the court-ordered dismantling of the studio-owned theater chains, the American movie industry spent the whole 1950’s and much of the 1960’s on the back foot versus the boob tube, resorting to one faddish gimmick after another in the hope of luring people out of their living rooms. It was a different story, though, after 1968. With the final demise of the Production Code, the studios could at last say without exaggeration or ballyhoo that your local movie theater offered attractions impossible to find on the small screen. That wasn’t too big a problem for the networks at first, because most mainstream movies released to theaters during the year or so following the Code’s replacement by the MPAA’s new four-tiered rating system were approved for general audiences. In 1968-1969, that meant they’d have faced no impediments under the old system anyway. But if you look at the top ticket-sellers for 1968, you see something worrisome indeed from a network boss’s point of view. The #7 box-office grosser in the country that year was Rosemary’s Baby, an R-rated horror film that was not only a huge moneymaker, but also a fair critical success and ultimately one of 1968’s most influential pictures. Normally any movie that performed like Rosemary’s Baby would be a tempting target for ripoffs, especially given the steadily growing importance of TV-original features to the networks’ business model. But how the hell were the big broadcasters supposed to get a movie that hinges on fucking the Devil past FCC decency regulations, let alone their own Standards and Practices departments? Fear No Evil, the Universal Television production with which NBC launched its “World Premiere” program into a new weekly format to compete with ABC’s “Movie of the Week,” was an attempt to answer that question. Although it certainly won’t ever be mistaken for one of the era’s theatrically released occult horror films, Fear No Evil pushes the limits for late-60’s television pretty hard, with a bloody car crash, an explicit acknowledgement of devil worship, and a love scene that would have been a lot for the censors to stomach even if one of the participants weren’t a demon, a dead man, or possibly somehow both.

Physicist Paul Varney (Bradford Dillman, from Moon of the Wolf and Lords of the Deep) stumbles through one of LA’s most famous indoor shooting locations in a daze, then makes a seemingly entranced beeline for Wyant’s Antiques and Treasures. It’s almost midnight, and the shop has been closed for hours, but the proprietor (Harry Davis) is still up and still on the premises doing various sorts of bookkeeping and administrative work. Wyant is annoyed in the extreme to have what he plausibly takes for a drunk, a dope fiend, or a loony banging on his door at this hour, but the fat wad of cash that Varney waves in his face persuades him to be indulgent. For all his urgency to be let in, the addled scientist clearly has no idea what he actually wants from the shop— that is, until he spots a huge, ungainly, and rather ugly mirror. Varney unhesitatingly pays Wyant the $300 he asks for the eyesore, and gives orders for it to be delivered to his apartment the following day. Paul will have almost no memory of any of this in the morning, leaving him essentially powerless to explain the purchase to his fiancée, Barbara (Linda Day George, of Cruise into Terror and Beyond Evil, who was still just Linda Day in 1969).

The next evening, Paul and Barbara entertain a visit from one of Varney’s senior colleagues at the laser lab where he works, a fellow named Myles Donovan (Carroll O’Connor). The older scientist hasn’t come to hang out at their place, however, but rather to take them to a party at the home of an eccentric psychiatrist called David Sorrell (Louis Jourdan, from Amazons of Rome and Swamp Thing). Sorrell’s regular practice seems ordinary enough, but he’s also a student of things very far out of the ordinary indeed for a man of his profession. His hobbies include ancient religions, witchcraft, paranormal phenomena, and heaven knows what else in that vein. He’s also got a stage magician’s flair for showmanship, as he demonstrates that night when one of his guests scoffs at the possibility that he could really believe in any of that nonsense. Producing a locked metal coffer from a cabinet in his sitting room, Sorrell regales the crowd with the story of the mystery surrounding it: its reputedly African origin, its supposed consecration to an entity called the Seven Words of Agony, and the verified fact that three of its previous owners— the only people known to have ever opened it— died in horrendous torment soon thereafter. Then he offers up the key to the box, daring his rational, modern, skeptical guests to put their nerve endings where their mouths are. When there are no takers, Sorrell unlocks the coffer himself… and pulls out an unfiltered cigarette. (It’s 1969, so nobody points out that the lung cancer he’s going to get from smoking those things will give him all the torment he can stand one of these days.) A funny thing happens, though, while Sorrell is holding court on the subject of demonology, rattling off a list of the major devils. Varney surprises everyone— himself included— by blurting out “What about Rakashi?” He has no more idea what he meant by that than he has why he bought that fool mirror last night.

Nor will Paul ever puzzle out his obscure motive in either case, for he has only a few more hours to live. Sorrell’s party goes on until after dawn, but Varney has big plans for Saturday. He’s an antique car buff, and he’s taking both Barbara and his Great War-vintage Stanley Steamer to a rally later in the morning. They’re about halfway there when Paul loses control of the vehicle, and rolls it down a steep hill. Barbara, thrown from the car’s open-sided passenger compartment on the way down, receives no injuries that a short hospital stay won’t fix, but Paul is crushed during one of the Stanley’s several lateral flips.

Now the natural thing to assume here is that that’s what you get for trying to negotiate a tricky road in a Brass Age car, on zero hours of sleep, after an all-night 60’s cocktail party. But while exhaustion and hangover might explain Paul’s uncharacteristic crabbiness with Barbara during the drive, the wreck itself had a much more sinister cause— and one obviously if mysteriously connected to the mirror from Wyant’s Antiques and Treasures. When Varney first saw the mirror in the shop, the image in the glass transformed momentarily into an infinite reflection of itself, seeming to form a corridor from which an ineffably malign double of Paul— a double distinctly different from any mere reflection— emerged. It was evidently this that decided him on purchasing the thing. When Paul lost control of the car, it was because he started seeing the same evil doppelganger leering at him from the rear-view mirror. So although Dr. Sorrell looks in on Barbara shortly before her scheduled release from the hospital merely out of concern for her emotional wellbeing, there’s excellent reason to imagine that by doing so, he will find occasion to exercise his interest in the inexplicable.

Sorrell isn’t Barbara’s only visitor that afternoon, either. Paul’s mother (Back from the Dead’s Marsha Hunt) comes by, too— which is unexpected, because the old lady has always detested her prospective daughter-in-law on the grounds that she was unworthy to join such an aristocratic family. But Paul’s death has evidently softened Mrs. Varney’s heart, for the thing she desires most right now is the company of someone else who loved him, with whom she can share her grief. Indeed, Paul’s mom goes so far as to invite Barbara to move in with her at the Varney mansion! But would you believe that when Barbara settles in, she discovers that her hostess has installed that peculiar mirror of Paul’s in the room where she’ll be staying?

The consequences of the old dame’s disposition of her son’s personal effects begin making themselves felt very swiftly. Each night, Barbara gets out of bed in a trance-like state to stand in front of the mirror. And every time, Paul appears in the glass as if emerging from an infinite corridor, looking like the average of his true self and his wicked double, and makes love to Barbara’s reflection. It would be a pretty sweet arrangement for Barbara, if it weren’t so obviously evidence that the girl was losing her mind. Also, there eventually start to be side effects, almost as if Barbara were being visited by a vampire. She increasingly feels drained and ill following her bouts of hypno-necrophilia, which furthermore leave minor but bloody wounds on her throat (albeit not of the familiar fang-mark variety). Barbara books an appointment with Dr. Sorrell, who at first assumes that she’s in the grip of an unhealthy erotic obsession brought on by the trauma of her fiancé’s death. But after he hypnotizes her during a house call, what she reveals in her trance leads him to fear that something much stranger is afoot.

While Barbara languishes and Mrs. Varney frets, Sorrell launches an investigation more in keeping with a detective’s line of work than a psychiatrist’s. He visits Myles Donovan at the lab seeking insight into Varney’s interests and relationships. He drops in at Wyant’s Antiques and Treasures to ask about the provenance of the mirror. He meets with Varney’s former secretary (Jeanne Buckley), and learns thereby that Varney had spent the evening before the doctor’s party with a circle of mystics who meet in the offices of the Metaphysical Research Center. And when he goes to the offices in question (Oh, look— it’s the very building that Varney was stumbling through in the opening scene!), Sorrell finds the atmosphere of the place disconcertingly shady, suggestive of something more dangerous than a clubhouse for cranks and weirdoes. Indeed, the psychiatrist finds his contact there, a woman by the name of Ingrid Dorne (Katherine Woodville, from Clue of the New Pin and Black Gunn), so obviously untrustworthy that he contrives to pocket a tape reel that he finds, marked with the date of Varney’s visit. Listening to that tape confirms all of Sorrell’s worst suspicions. It records a summoning ritual in which Varney was placed under hypnosis to become the host of something called Rakashi, which the cultists’ chant characterizes as “Lord of Light, Lord of Lust, Lord of Blood.” Evidently something went wrong, though, because Paul went berserk in his trance, and forced his way out of the Metaphysical Research Center amid what sounds like total panic and confusion among the rite’s other participants. Deciding that he’s going to need backup, Sorrell calls in Harry Snowden (Wilfred Hyde-White, of Ten Little Indians and The Ghosts of Berkeley Square), his mentor in spook-busting, who comes across as a more avuncular version of Dennis Wheatley’s Duc de Richelieu. Between the two of them, maybe they can figure out what this Rakashi is, what sort of threat it poses to Barbara, and most importantly, how to send it back to wherever it came from.

Although Fear No Evil isn’t especially great in any absolute sense, it’s extremely impressive in light of the forces arrayed against making such a movie for 1960’s television in the first place. The openness with which the film acknowledges the sexual dimension of Barbara’s supernatural affliction would be extraordinary for a TV production even in the decade to come, particularly considering that Paul squishes himself to death beneath his Stanley Steamer before the couple have their relationship formalized by marriage. The longest and most involved love scene between Barbara and her dead, demonically possessed fiancé is a real monocle-popper, despite being both tightly framed and fully clothed. Above and beyond the conceptual perversity of what’s happening in the mirror, Linda Day and director Paul Wendkos imply as hard as they dare that back in her physical body, the semi-conscious Barbara is masturbating with all her might. And in marked contrast to the other occult horror films of the post-Rosemary’s Baby era, Fear No Evil conspicuously avoids any suggestion that the existence of demons implies the existence of God. Indeed, the stated position of the Rakashi cult, once Sorrell meets its leader face to face, is that the opposite is more likely to be true. These are practical people, rather than religious believers in the modern sense of the term; they want to be on the side of power, regardless of what their moral sensibilities might tell them.

That notion of pragmatism and practicality in the face of the supernatural is Fear No Evil’s most consistent and interesting feature. The cultists don’t think of themselves as evil, even though they unhesitatingly acknowledge that Rakashi is. But looking at the state of the world in 1969, they’ve concluded that evil— or more accurately, Evil— has the upper hand, and that humanity has no choice but to reach a modus vivendi with it. It’s altogether logical that researchers in applied physics, with strong ties to the military-industrial complex, would hold such a position, too. After all, they make a hundred small, ad hoc versions of the same commitment on the job every day. Meanwhile, there’s a different but no less satisfying logic in the idea of the staff at a laser lab throwing in with a demon of light, and in mirrors being the artifacts through which that demon projects its power into the mortal world. Then on the opposite side, David Sorrell embodies his own sort of supernatural pragmatism. The truest answer to his party guests’ scandalized questions about whether he believes in all this stuff is no— or at least not in the comprehensive, systematic way that they’re implying. But he doesn’t comprehensively, systematically disbelieve in it, either, and when his investigations into a potentially paranormal phenomenon indicate that something truly outside the realm of consensus reality is going on, then he follows the evidence wherever it leads. Sorrell’s informal first session with Barbara is one of the best character-development scenes you’ll find anywhere, because it shows him operating realistically like a psychiatrist while subtly hinting at the same time that he recognizes some possibility of having to employ his more specialized expertise as well. It makes Sorrell the perfect opposite to the Rakashi cult, because he too is a man of science, led by the scientific method to conclusions that most would reject as inherently unscientific.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact