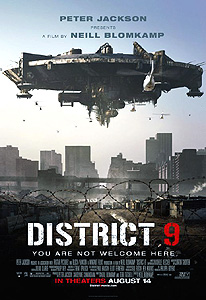

District 9 (2009) ****

District 9 (2009) ****

Back in 2005, Microsoft, Universal, and 20th Century Fox launched a collaborative effort to produce a film adaptation of the video game Halo. The software firm was to have creative control of the project, Universal would handle both production and domestic distribution, and Fox would hold the overseas rights to the movie. Peter Jackson came onboard as executive producer in December of that year, bringing with him the Weta Workshop effects house that had done such sterling work on King Kong and the Lord of the Rings trilogy, and the three companies had the script in a shape that they liked by the first quarter of 2006. Finding a director took a little longer. Although Guillermo del Toro was considered for the job, it eventually went to a virtually unheard-of South African filmmaker named Neill Blomkamp, who had worked primarily in TV commercials up to then. All seemed to be going well for several months, but then Universal, Fox, and Microsoft began squabbling over money, leading first to the studios backing out of the deal, and then to them turning on each other over who was supposed to pick up the tab for the considerable sums already spent on preproduction. Halo was officially put on hold late in 2006, but Microsoft retained Jackson, Blomkamp, and Weta, keeping them busy with a trio of short films intended to support the marketing blitz for the game’s second sequel. Nevertheless, Halo the movie appeared firmly ensconced in Development Hell by 2007, and it’s still there as of September 2009.

One very good thing did come of the Halo fiasco, however. Bummed out over how his attempt to give a talented young director his first big break had gone awry, Peter Jackson established forever his credentials as a stand-up guy by offering Blomkamp access to Weta and $30 million with which to make any damn movie he pleased. Remarkably, what Blomkamp did with all that money was to mount an ambitious feature-length enlargement of Alive in Joburg, a six-minute short he had brought forth in 2005. Alive in Joburg essentially took the back-story behind Alien Nation— a race of extraterrestrials who had been used as slave labor by a different alien species flees to Earth and attempts to assimilate— and turned it into a brief but unsettling musing on the troubled state of race and ethnic relations in South Africa, presented in the guise of a fake documentary. District 9, the feature-length version, features some pseudo-documentary elements, too, but the talking head and newsreel footage is interwoven with a more conventional cinematic narrative about a thoroughly un-noteworthy man who gets a much more rigorous education in the workings of oppression than he ever considered asking for.

In 1982, aliens came to Earth. Contrary to what sci-fi fans have long been trained to expect, however, they did not set their huge, roughly mushroom-shaped spacecraft down in Washington or Moscow, or even in a second-rank world-power capital like London, Tokyo, or Beijing. No, when the extraterrestrial vessel came to a stop, it was over Johannesburg, South Africa. Nor did the aliens exactly land. Although retrospective analysis of video footage taken at the time later revealed that some manner of large device did detach itself from the ship’s underside and descend toward the city, the ship itself hung silent and motionless in the sky above Johannesburg for months before somebody in authority grew sufficiently impatient to dispatch a helicopter-borne commando team to reconnoiter. When the soldiers cut their way into the giant craft, they found it occupied by about a million crustacean-like, semi-humanoid (which is to say, bilaterally symmetrical, bipedal, and cephalized) creatures about the size of a Caucasian woman, living in conditions noxiously reminiscent of the hold of a transatlantic slave-ship. Immediately, a sociopolitical event without precedent in human history became an equally unprecedented humanitarian crisis. The thing that fell off the ship upon its arrival over Johannesburg had apparently been the vessel’s command module, without which none of the primary systems would function. Also, there were indications that the aliens were a eusocial species in which a few dominant individuals directed the efforts of vast numbers of their fellows. At the very least, it seemed difficult to reconcile the sophistication of the visitors’ technology with their limited intelligence and near-total lack of personal initiative. And if there had been a caste of planners and thinkers among the extraterrestrials, it was plain enough that none of them had survived to greet the boarding party. The aliens would have to be treated as refugees and evacuated from their inoperative ship.

That being the case, whoever had been piloting the spaceship during its final approach picked exactly the wrong endpoint for the journey between the stars. The Anglo-Afrikaaner minority that ruled South Africa in the early 80’s couldn’t bring themselves to treat people with a little extra melanin in their skins with the decency due a sentient being— what do you suppose they made of a million five-foot, upright shrimp who were anatomically incapable of speaking any human language? Now, to be fair to the good people of Joburg, the aliens were not exactly model citizens. They seemed to have little concept of property rights, laws, or civil authority, and although they showed no talent for organization or problem-solving above the most basic level, their survival instincts were sharp enough to give them an unfortunate facility with theft, breaking and entering, and small-scale violence. And because they were a lot stronger than the average man, the consequences of that small-scale violence could be disproportionately severe. For a time, the municipal authorities tried to herd the aliens into the townships where the city’s black residents were forced to live, but the blacks turned out to mix no better with the newcomers than their paler-skinned neighbors. A wave of horrific speceis riots led in the end to a new kind of Apartheid, as the aliens were rounded up and corralled in a township all their own.

Some two decades after its establishment, District 9 is as wretched and dysfunctional a place as ever. Nigerian gangsters led by the vicious Obesandjo (Eugene Khumbanyiwa) control most of what passes for the district’s economy, doing booming business in smuggled military weapons, interspecies prostitution, and cat food (which has some unexplained addictive effect on the aliens). Though Apartheid no longer applies to black or coloured South Africans (“coloured” in this context meaning dark-skinned people of mixed ethnicity, often including Indian, Indonesian, and Malay elements as well as African and European), the extraterrestrials remain fourth-class citizens subject to such punitive legal handicaps that they must obtain government licenses even to breed. An aliens’ rights movement does exist in the country, but it is pitifully weak beside the utter loathing that the “prawns” face from most humans of all races. Even the aliens’ derelict spaceship is a bone of contention, for it still hovers above the city, uglying up the skyline and mightily inconveniencing commercial air traffic. Unable to move under its own power without the command module, it is also too big to be budged by any means at human disposal, and too low over inhabited areas to be blown up safely. Eventually, the South African government concludes that the time has come to remove the aliens from Johannesburg altogether, and undertakes to shift them all to a self-contained tent city that is transparently an internment camp in all but name. An evacuation on that scale will require an enormous investment of resources, though, together with a commensurately enormous amount of organizational expertise, and thus it is that the government has enlisted the aid of a Haliburton-like mega-corporation called Multinational United to manage the resettlement of the aliens. MNU will have the full support of both the South African military and the Johannesburg police force, but they have also subcontracted with a private security firm (think Blackwater) to provide a team of elite mercenaries led by former special forces officer Koobus Venter (David James).

There are two major complications facing the resettlement initiative. First off, the folks in Pretoria are not eager to resume being international pariahs that they were in the 80’s. MNU will have to comply with certain legal niceties, and the public relations profile of District 9’s reclamation will have to be carefully stage-managed. Company boss Piet Smit (Louis Minnaar) appoints his son-in-law, Wikus van de Merwe (Sharlto Copley, who you’ll never believe had no acting experience beyond a single scene in Alive in Joburg), to the all-important post of field coordinator for the evacuation, charging him with the responsibility to serve formal eviction notices to all the inhabitants of District 9, quickly, thoroughly, and with a minimum of politically undesirable violence. The second complication is less obvious, and has exceedingly sinister implications. The alien ship was stocked with an arsenal of extremely advanced military weapons— everything from hand-held gauss guns that cram artillery-sized firepower into a package no heavier than a modern assault rifle to power-armor suits comparable to the titular mecha in Metal Skin Panic: Maddox 01— and much of that hardware was removed along with the passengers back in ‘82. These incredible armaments were of no use to their new owners, however, because all were fitted with biometrically enabled trigger mechanisms, keyed to the aliens’ own DNA. Multinational United has been at the forefront of research into outsmarting the genetic trigger locks, but even they apparently haven’t made any headway to speak of. That being the case, does anybody else get just the tiniest inkling that life for an alien inside MNU’s spiffy new internment camp might fall a little closer to the Auschwitz end of the spectrum than the Manzanar?

As for Wikus van de Merwe, he’s an odd candidate for his new job. It would be hard to find a more complete nonentity, and it’s tempting to speculate that Smit put him in charge primarily because he’d look so harmless on the TV news, or because he seems so incapable of standing up to Venter in a disagreement over how to handle the mission. But if indeed that was the plan, Smit didn’t think it through nearly far enough. When Wikus leads a team of cops and mercenaries into District 9 to begin handing out evictions, things go wrong in exactly the way that having a civilian field coordinator was supposed to prevent. The plan is simply to get as many acknowledgements as possible, regardless of whether the aliens understand what they’re being asked to sign (in fact, everybody seems to be banking heavily on the aliens not understanding the documents Wikus and his men hand them), but van de Merwe has little inclination and less ability to control the behavior of his armed escort. The cops and mercenaries brutalize or murder nearly every alien who offers them more than the slightest resistance, and the resettlement program begins on a note of potential political fiasco.

In the long run, however, the misbehavior of van de Merwe’s backup is less important than what happens that afternoon at the shanty of an alien called “Christopher Johnson.” You remember the speculation that there had originally been a few smart extraterrestrials bossing around multitudes of dumb ones? Well, Johnson’s existence seems to prove that hypothesis correct, for not only does he effortlessly read and comprehend the eviction order that Wikus gives him to sign, but he refuses to comply on the grounds that the eviction itself is illegal. Talk about a political fiasco in the making! Wikus tries several tactics to persuade or coerce Christopher into signing his eviction, but the extraterrestrial refuses to budge. In the end, van de Merwe has one of his cops place Johnson under arrest, then proceeds to search his shack for pretexts on which to charge him with some crime sufficiently serious to get him out of the way until the resettlement is complete. In doing so, Wikus finds some stuff that he’s not at all used to seeing in an alien’s shack— a jury-rigged chemistry lab, masses of functioning computer equipment, and a small, cylindrical device that bears no resemblance to anything he recognizes. The cylinder is filled with viscous fluid, and when Wikus examines it, some of that fluid spills out onto his face and arms. One of those arms is maimed shortly thereafter when the police pick the wrong alien to provoke (Christopher Johnson gets away in the ensuing disorder), and some of the spilled fluid from Johnson’s device finds its way into van de Merwe’s bloodstream through his wounds.

Whatever the true purpose of the stuff in the cylinder, mixing it with human blood has the effect of rewriting the victim’s DNA to resemble that of the aliens. District 9, in other words, is about to become the strangest and bloodiest imaginable remake of Watermelon Man. Wikus becomes violently ill at the party his family throws in celebration of his recent promotion, and when he reaches the hospital, the emergency room doctors discover that beneath the dressings on his wounded left arm, the limb has somehow changed to become exactly like an alien’s. Van de Merwe is understandably quarantined at once, but matters take a distinct turn for the horrible after that. The site of the quarantine is MNU headquarters, and Piet Smit dishonestly informs Wikus’s wife, Tania (Vanessa Haywood), that he died of septicemic shock in the hospital. The motive behind all this is that Smit has recognized his subordinate’s condition as the probable key to defeating the trigger locks on the aliens’ weapons— and once a round of increasingly ghoulish experiments reveals that Wikus can indeed operate the full range of armaments, Smit orders him vivisected in the hope of unlocking the secret of his genetic dual citizenship. Luckily for Wikus, MNU’s mini-Mengeles failed to anticipate that his alien arm would possess alien strength, and the restraints on his gurney are no serious obstacle to him. Wikus escapes, but the only remotely safe place for him now is in the scrap and tar-paper labyrinth of District 9. Of course, since that’s also the only place where he might conceivably find a cure for his condition, an extended visit there would be the smart thing to do even if he weren’t on the lam from a corporation run by sociopaths with the municipal government of Johannesburg in its back pocket.

The thing I like best about District 9 is that it is easily the most morally confusing movie I’ve seen in wide theatrical release in years. It isn’t only that Wikus van de Merwe is nobody’s idea of a hero— he doesn’t even qualify as an antihero. He’s just a selfish, ignorant, bigoted, cowardly little twerp without much in the way of either intelligence or imagination, who falls into a grotesque situation that is lightyears beyond his coping ability, and who fails nearly every test of bravery, decency, and compassion until he is finally confronted with one in which failure is literally not an option. We meet him in the midst of preparing to take part in a monstrous crime against humanity (and make no mistake, the uprooting of the aliens is a crime against humanity, even though its primary victims are not human), and witness his pride in having been judged worthy to help commit it. We see Wikus treat the destruction of an incubator full of unlicensed alien eggs as an occasion for thrills and excitement— not sadistically, but in childish incomprehension of the act’s moral dimensions. When Wikus meets Christopher Johnson for the second time, correctly assuming that the alien knows something about his accelerating transformation, he presents himself as the aggrieved party, oblivious to the fact that none of this would be happening if he hadn’t invaded and ransacked Christopher’s shack in an attempt to trump up some bullshit criminal charge against him. It never occurs to van de Merwe to be grateful to the alien when he offers to help reverse the metamorphosis (which will require a visit to the derelict spaceship, and before that, the recovery of the cylinder that Wikus confiscated from the shack), nor does he ever appreciate the extent to which his well-being is not Christopher’s problem. Van de Merwe frequently demonstrates his preparedness to abandon or betray Johnson when standing up for the alien would mean a serious risk to his own ass, even though it takes the revelation of what goes on in MNU’s fourth sub-basement to make Johnson demote fixing the human’s DNA to priority-two status. And when Wikus finally does something outwardly heroic, using a power-armor suit stolen from Obesandjo’s mob to defend the launch of the long-lost command module, the circumstances are such that he is impelled to it by the very same cowardice and self-interest that have driven his actions all along. He eventually exhibits the symptoms of courage, but the condition itself never manifests in him. Even so, however, it is impossible to hate Wikus van de Merwe. He is contemptible, certainly, but he has a few important redeeming qualities (his genuine and obvious devotion to Tania being foremost among them), and in the final assessment, he is much too paltry a man to inspire anything as powerful as hate. Disgusted pity seems about the most appropriate response.

Similar uncomfortable ambiguities can be found all throughout District 9. Koobus Venter, for example, is far less clear-cut a villain than he seems at first glance. He may be thoroughly and horribly evil, but despite his prominent role in the story, he is but a small cog in an evil machine. Venter is a hard-ass for hire, the sort of man that people like Wikus turn to when they lack both the moral fiber to do good and the courage to do evil. Men like Venter do the wet work so that men like van de Merwe can reap the benefits of systemic wrongdoing, yet still be able to look at themselves in the mirror each morning. When Wikus contends with Koobus, he contends with the mechanism that supports his own privilege— and that of his wife, his mother, his coworkers, and everyone else in the country who drew a winning number in South Africa’s high-stakes genetic lottery. And while we’re on the subject of parallels with the real South Africa, it’s worth looking closely at how District 9 treats its black characters. In what might be the film’s ballsiest move, it is faintly but unmistakably implied that the demise of human Apartheid in this fictional world stemmed in large part from the arrival of the aliens; here, at last, was a group of people whom whites and blacks could join hands to hate and oppress in concert. That state of affairs sadly resembles the real-world plight of refugees from the social, political, and economic implosion of neighboring Zimbabwe, who flee across the border into stable and relatively prosperous South Africa, all too often to be treated as a subhuman nuisance by black and white South Africans alike. But at the same time, the movie’s blacks come in for an enormous amount of casual condescension and disregard from their white colleagues— witness in particular van de Merwe’s patronizing treatment of Thomas the cop (Kenneth Nicosi), or how Fundiswa Mhlanga (Mandla Gaduka), Wikus’s black assistant, ends up being the only civilian on the eviction mission without a bulletproof vest. Bigotry in District 9, in other words, has layers upon layers, which brings me to the distinctly problematic subject of Obesandjo and the Nigerian mob.

The real issues here are likely to be invisible to American viewers (who might at most experience a twinge of discomfort at the parallels between Obesandjo’s gang and the savage black natives of the Bad Old Days of Hollywood), and Blomkamp’s handling of the Nigerians is to some extent defensible in the broader thematic context of the film. The most contentious aspect of the Nigerians’ portrayal— Obesandjo’s pet Juju priestess (Hlengiwe Madlala), and her advice to the crime lord that eating alien flesh will enable him and his men to wield the extraterrestrial weapons they’ve captured since their migration to District 9— was plainly designed to mirror Piet Smit’s secret vivisection lab, and has roots in several traditions of African folk belief. The trouble is that the specifically Nigerian versions of those traditions are embattled at best and moribund at worst, making it extremely unlikely that Obesandjo would put much stock in them. Furthermore, Blomkamp has stated that his most direct inspiration for the alien-eating plot thread was a rash of reports from Tanzania about unscrupulous pagans cannibalizing albinos in the hope of acquiring some sort of supernatural power. Leaving aside the issue of how credible those reports might have been, Tanzania is nowhere near Nigeria. It’s a misstep that would be unfortunate anyway in a movie about the evils of bigotry and xenophobia, but it’s made doubly so by the fact that District 9 hails from South Africa, where the sizeable Nigerian immigrant community is looked on with about as much favor as the Algerians in France, the Turks in Germany, or the Mexicans in much of the United States. Blomkamp, it would appear, still has a bit further to go himself.

But Obesandjo notwithstanding, District 9 is on the whole an extremely successful attempt at what science fiction does best. It presents a fully believable alternate world, and uses it to take a pretty hard look at the one we actually live in. It is incredibly convincing from a visual point of view, and I shake my head in mingled awe and despair as I observe that it looks as good as it does despite costing a minute fraction of what Michael Bay spent on the execrable Transformers. It also uses its extraordinary visual effects as tools in service of its primary theme, rather than as ends unto themselves. Blomkamp’s decision to make the aliens as physically inhuman as the same basic body shape would allow, and to give them a culture that would mix very poorly with our own, was a masterstroke, forcing the viewer to overcome exactly the same prejudices that animate Wikus van de Merwe in order to gain emotional access to the real hero of the story. All too often, allegorical calls for tolerance stake everything on the dubious assertion that we’re not so different after all; District 9 takes the stricter position that we owe each other decency anyway, no matter how great our differences.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact