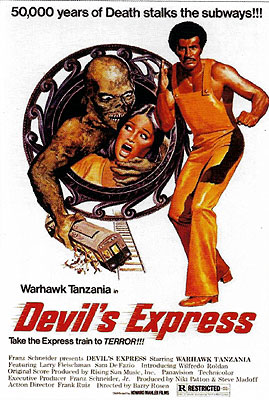

Devilís Express / Gang Wars (1975/1976) -***Ĺ

Devilís Express / Gang Wars (1975/1976) -***Ĺ

I wanted to begin this review with a short biographical sketch of its star, Warhawk Tanzania. I mean, you just know anybody with a name like that has got a story to go along with it! Unfortunately, though, it seems that no one who knows that story is telling it anyplace that I can find, so I can offer only a few tantalizing fragments of information. He was born in 1943 as Warren Hawkins, or possibly Warren Hawks (ohÖ now I get it), and he was living in Brooklyn at the time of his brief brush with something slightly resembling fame. Near as I can tell, that brush came, as they so often do, simply from being in the right place at the right time. Specifically, Warhawk Tanzania was studying Okinawan karate under a former US Marine and Korean War veteran by the name of Frank Ruiz when Ruiz was approached by someone in the employ of Howard Mahler Distribution to act as fight coordinator on a series of homegrown martial arts movies to supplement the ones that the company had recently begun importing from Hong Kong. Tanzania may not have been Ruizís most accomplished or even most promising student (that would almost certainly have been Wilfredo Roldan, who would succeed Ruiz as hanshi of the Nisei Goju Ryu dojo when the grandmaster himself retired in 1979), but he arguably was the most charismatic, at least in the eyes of the young, black moviegoers who were already emerging as the core chopsocky audience in American cities. He ended up starring in two of Mahlerís three shot-in-New-York karate flicks before melting back into regular life. The first of these was Force Four, evidently a fairly straightforward combination of blaxploitation and martial arts which Iím sure Iíll get around to one of these days. But the movie that Tanzania, Ruiz, and pretty much everybody else involved truly deserves to be remembered for is Devilís Express, a barking-mad exercise in genre-blending that adds occult horror to the mix with an ancient Chinese demon setting up shop in the subway tunnels under Brooklyn. For a ready handle on the tenor of Devilís Express, imagine that Raw Meat, Miami Connection, Avenging Disco Godfather, and Voodoo Black Exorcist were somehow all the same film.

China, 200 BC. A scar-faced samurai (waitÖ), played by Yoshiteru Otani, leads a group of Shaolin monks (wait!) deep into the woods, bearing a large and ornate chest. Under the samuraiís supervision, the monks lower the chest into a hard-to-find and harder-to-enter cave, where they leave it after placing a talisman of some kind in a niche on its lid. Then, at the entrance to the valley containing the cave, they erect an ominous cairn topped with a human skull. Finally, the monks all submit to beheading by the samurai, who slits his own throat once the job is done.

21ĺ centuries later, in Brooklyn, martial artist Luke Curtis (Tanzania) is fending off the latest attempt by one of his pupils, policeman Cris Allen (Larry Fleischman, of The Yum-Yum Girls), to recruit him onto the force. Allen basically hopes to co-opt Curtisís standing with the local black and underclass white communities to raise the esteem of the department, but Luke isnít having it. After all, whatever moral authority he possesses stems in no small part from his lack of ties to suspect organizations like churches, political machines, or the NYPD. Besides, heís got no time for taking on new projects right now, because he and his right-hand man, a rather slimy honky by the unlikely name of Rodan (the aforementioned Wilfredo Roldan, who played alongside Tanzania in Force Four, and alongside some of his other Force Four costars in Velvet Smooth), are about to journey to China in order to study under an internationally famous master of their art. (Note that this development rather muddies the issue of what specific form of asskickery our heroes are supposed to practice. One wouldnít ordinarily expect to find a world-class hanshi of Ruizís Okinawan karate in China, after all. But since Wilfredo Roldan really did study arnis in the Philippines later in his career, maybe weíre meant to infer a Bruce Lee-like ďlearn it all, and use whatever worksĒ approach. Or since Rodan invariably calls Curtis ďsifuĒ rather than ďsensei,Ē maybe Devilís Express is just plain eliding the distinction between kung fu and karate altogether.) Itís obvious from the get-go, however, that Luke and Rodan donít quite see eye to eye on the premise of the trip. For Curtis, this is first and foremost a chance to grow spiritually under the guidance of one who has already undergone such development. Rodan, on the other hand, sees only a unique opportunity to improve his fighting prowess for the sake of the escalating turf war between his drug-pushing gang, the Black Spades, and the rival Red Dragon mob. That wrathful, violent state of mind gets Rodan into trouble when Master Leung (Duncan Leung) sends him and Luke into the woods surrounding his compound to meditate in quest of spiritual visitation. Rodan gets a call from the Other Side, alright, but instead of bringing him enlightenment, it leads him to that box which the monks and the samurai were at such pains to hide all those ages ago. Luke (who receives his supernatural guidance from a wisdom-imparting snake) draws his friend away from the chest before he does anything as stupid as opening it, but arrives too late to stop him from pocketing the valuable-looking amulet affixed to the lid.

Neither Curtis nor Rodan thinks any more about the chest in the cave after they return to Master Leungís compound, let alone after they fly back to the States. The putrid and cadaverous demon that escapes from the box once the two men have left is evidently thinking quite a lot about them, however, because it follows them to Hong Kong, waylays a business traveler (Aki Aleong, from Sci-Fighters and Dragonfight), and possesses his body to stow away aboard a freighter bound for New York. Once there, it continues to home in on its liberator (or at least on the stolen amulet heís carrying), but finds the bright lights and cacophonous noise of a 20th-century city not at all to its liking. The demon finds the subway system sufficiently comfortable, though, and takes up residence somewhere far enough from any of the stations to escape notice, but near enough to them to find easy prey during the late-night hours when it prefers to go hunting.

The resulting pileup of corpses attracts official attention, of course, but detective Allen and his new partner, Sam Lawford (Stephen DeFazio), naturally start off by looking in entirely the wrong direction. The conflict between the Black Spades and the Red Dragons has entered a deadly new phase, and since the demon happens to do its killing beneath the neighborhoods disputed by the two gangs, the police proceed at first under the assumption that the monsterís victims are collateral casualties of the gang war. Even Luke Curtis assumes as much when Rodan is killed in the middle of an attempt to avenge Tom (Thomas D. Anglin), his recently slain best friend among the Black Spades. But when the intended victim of a late-night subway rape (Sherri Steiner, from Three on a Meathook and God Told Me To) reports that her attacker was seized and dismembered by some horrible, inhuman thing, Allen starts to suspect that the borough has a much weirder problem than battling street gangs.

Inevitably, though, itís Curtis who ultimately learns whatís really going on, and who accepts the responsibility to do something about it. His showdown with the leader of the Red Dragons (Yoshi Takashita) takes an unexpected turn when the gangster disavows any involvement in what happened to Rodan, even as he unhesitatingly cops to Tomís murder. Then the gangster offers to take Luke to see the one person in the city who knows not only of Rodanís true fate, but of what it portends for the world. The man in question is the elderly Tong boss who serves as the Red Dragonsí liaison to the Old Country. (Fuck if I know who plays him, though. The Tong boss isnít credited specifically, and no one alive would be even faintly recognizable under all that crap-lousy old age makeup anyway.) The way the old man tells it, Brooklyn is being stalked by a demonic entity called to Earth centuries ago by the wizard Master Lo Pan (!). It was trapped in mortal, physical form by a rival magician, who somehow siphoned off the better part of its power into an amulet which could be used to control or bind it. That, naturally, was the trinket that Rodan stole from the cave in China. The demon followed Luke and Rodan to New York because it hopes to capture and destroy the amulet, and thereby regain its full poweró so itís a damned good thing for everyone that one of the Red Dragons swiped the talisman from Rodan before the monster caught up to him. The only way to send the demon back where it came from more or less permanently is for someone pure of spirit to challenge it to a duel while bearing the amulet. Obviously that runs the very serious risk of giving the demon exactly what it wants, though, so the challenger had better be sure he has what it takes to win that fight!

I donít know about you, but if I had just read all of that, Iím pretty sure one of my first questions would be, ďOkay, but what the fuck is a ĎDevilís Express,í and what does it have to do with karate guys fighting ancient Chinese monsters?Ē The back-cover copy to the Code Red Blu-Ray disc of Devilís Express would have us believe that thatís what the locals called the late-night subway train between Brooklyn and Manhattan, and maybe thatís even true. I sure donít remember it ever coming up in the film itself, however, nor can I find the phrase attested anywhere besides this movieís title. As for its bearing on the plot, the short answer is that there isnít any, really. The longer answer is that I suppose we might assume that most of the creatureís victims are waylaid either after exiting or while waiting to board the train in question, but that still seems like an awfully flimsy justification for a title. Just the same, though, it is absolutely on-brand for Devilís Express to take its name from a never-uttered phrase of obscure meaning, with only the most tenuous connection to the actual story.

ďWhat does this have to do with anything?Ē is, after all, a question youíll find yourself asking a lot as you watch Devilís Express. The gang-war and monster-rampage storylines are connected only tangentially, and the movieís five screenwriters divide their attention between them in disorienting and counterintuitive ways. Generally speaking, anytime either plot thread looks like itís about to get really rolling, you can take that as a warning that a shift in focus is imminent. Devilís Express is also weirdly prone to distraction by what we might think of as local color. Itís always ready to drop everything for a comic relief bit poking fun at the rube-ish guilelessness of the almost painfully white Sam Lawford, or to spend a few minutes in the company of some quintessentially New York oddball. For example, one of the demonís victims is discovered by a demented bag lady (Sarah Nyrick), whom the camera follows from one end of a subway car to the other as she serially berates every single one of her fellow passengers; only after she steps out into the junction between cars does she stumble upon the corpse, thereby making her official contribution to the narrative. Similarly, the loony street preacher played by Brother Theodore (whom weíve seen before in Gums, and may someday see again in Nocturna) never actually does anything to advance the plot, but keeps showing up to hog the spotlight anyway. And then there are the two numbers-betting doofi who end up getting their asses kicked by the barmaid (Elsie Romanó another veteran of Force Four and Velvet Smooth) at their favorite hangout when they get a little too handsy with her. Itís in their scene that Devilís Express most reminds me of Miami Connection, since thereís no point at all to the proceedings except to give one more of Ruizís karate students a chance to show off her moves on camera.

Also reminiscent of Miami Connection are the way naÔve earnestness sits cheek-by-jowl with as much excessive violence as the impoverished production can afford, and the whiplash-inducing contrast between surprisingly impressive action and atrocious acting. Mind you, the extremes here arenít as great in either department as they were in Y.K. Kimís movie. For instance, Devilís Express has nothing as unapologetically sappy as Jimís reunion with his long-missing father, and itís clear enough that when Luke talks of brotherhood and spiritual improvement, we should be reading it specifically through a lens of black liberation. This film therefore has a politically subversive edge that Miami Connection lacks, which can be seen even in its gentlest moments. And on the action front, Devilís Express had no one of Woo-Sang Parkís caliber behind the camera, so that Tanzania, Roldan, and the other obviously skilled martial artists from Ruizís school are consistently let down by director Barry Rosenís handling of the fight scenes. Forget choreographyó Rosen canít even figure out where to place the camera so that it looks like the fighters are landing their punches and kicks! To be fair, Devilís Express seems to have been Rosenís first gig as a director, and his only other credit in that capacity was for a low-wattage sexploitation movie (in which one would expect to see nary a fist-fight), so at least the man seems to have caught on quickly to his own limitations. Still, itís frustrating to see the one form of talent that this cast possessed undermined at every turn through no fault of their own.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact