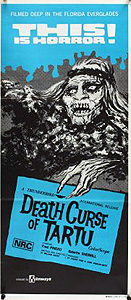

Death Curse of Tartu/Curse of Death (1966) -**½

Death Curse of Tartu/Curse of Death (1966) -**½

A lot of places have been dubbed “the other Hollywood” over the years (including even the San Fernando Valley, the LA neighborhood immediately adjacent to Hollywood, which has been the de facto headquarters of the American porn movie industry since the late 1970’s), but the city with the strongest claim to the title might well be Jacksonville, Florida. Indeed, Jacksonville was in the movie business before Los Angeles, with its first permanent film studio opening way back in 1908. There was a big difference between Jacksonville and Hollywood, though, even at the beginning; whereas the people who went to LA to make movies starting in 1911 were looking to escape from the monopolistic (and occasionally gangsterish) practices of the Edison-dominated Motion Picture Patents Company, Jacksonville was for all practical purposes the winter retreat of the firms that made up the aforementioned trust. New York in winter was a terrible place for filmmaking in the early years of the 20th century, and once Kalem Studios had pointed the way to the northeastern corner of Florida, the New Yorkers— Edison, Selig, King Bee, Lubin, and quite a few others— wasted little time in following. There were some important Jacksonville-based startups, too (most notably Metro, later to become the first “M” in MGM), but for the most part, the Floridian film industry remained a colonial outpost of New York through the end of the last century’s teen years.

Naturally, that was a big part of the reason for Jacksonville’s decline as a movie town during the 1920’s. For those who were trying to dodge the MMPC monopoly, Florida was nowhere near far enough away from New York, and Metro’s move west was not the only example of California-bound talent migration. World War I and the 1918 flu epidemic weren’t kind to northern Florida, either, causing a noticeable shrinkage in the region’s population. Local politics turned against filmmaking in 1917, with the election of Mayor John W. Martin, who was loudly moralizing against the movies before the Dos, Don’ts, and Be Carefuls were even a twinkle in Will Hays’s eye. And most importantly, the more successful the Hollywood studios became, the more their business model resembled that of the New York trust they had supplanted. Jacksonville remained a major nexus of production for race pictures until the end of the silent era, but by 1930, there wasn’t much for Floridian filmmakers to do at home except to shoot newsreels, educational shorts, and industrial training films.

Or so it was, anyway, until 1948, when a seven-to-one majority of the US Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Federal Trade Commission in United States v. Paramount, and ordered the dismantling of vertical integration throughout the motion picture business. The studios were forced to sell off their theater chains, and large-scale block-booking was disallowed, leaving the industry titans severely weakened at exactly the moment when cinema first began facing serious competition from television. The “Big Eight” (MGM, Paramount, Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox, RKO, Universal, Columbia, and United Artists) responded by making fewer, more carefully vetted films; the newly emancipated theaters responded by seeking replacement product wherever they could find it; and the massive dislocation of the old supply-and-demand balance opened up unprecedented opportunities for would-be producers who had formerly been shut out by the studio system. Some of these new players were Hollywood independents, like American International Pictures. Others were importers of foreign films, like Joseph Levine. And others still were small-timers all over the country, eager to expand beyond the likes of sex-hygiene one-reelers for the armed forces and scare films for driver’s ed classes. In places like Jacksonville, where there was plenty of production capacity lying fallow, the time was ripe for a golden age of cheaply made and regionally distributed exploitation movies. As the 1960’s dawned, Florida (including not just Jacksonville, but Miami as well) had come full circle, becoming both an attractive winter shooting location for exploitationeers based in New York and Chicago, and home to an indigenous, drive-in-oriented filmmaking scene.

That brings me to William Grefe. Unlike a lot of the drive-in luminaries who worked in Florida during the 60’s, (Doris Wishman, Herschell Gordon Lewis, Joseph Sarno, etc.), Grefe was actually from there, and he remained based in the Sunshine State throughout his career. He had a nearly Corman-like eye for emerging trends, and while he was never the first to do anything, he was quite frequently the second. Also like Roger Corman, Grefe got his start as a feature director with a couple of racing movies, Checkered Flag (essentially what you’d expect) and Racing Fever (about power-boat racing, rather than the usual dragsters or stock cars), before moving on to other, more profitable pastures. His first step in the direction of such bigger and nominally better things as Mako: The Jaws of Death was the mind-boggling teens-vs.-monsters flick, Sting of Death. The second came literally weeks after that film was in the can, when it became clear that the distributors (the newly launched and very optimistically named Thunderbird International Pictures) would be unable to find Sting of Death a mate for the all-important double bill before the inception of drive-in season in mid-April of 1966. Grefe wrote Death Curse of Tartu during a single 24-hour blowout, and was out in the Everglades shooting just over a week later.

Death Curse of Tartu follows a template that has been in wide use among lousy American horror movies since at least 1922’s The Headless Horseman— hook the audience in with something cool early on, so that maybe they won’t notice you boring the shit out of them until at least the end of the second act. A cowboy (Brad Grinter, who would later earn lasting infamy as the director of Blood Freak) lets himself into a cave somewhere in the Everglades. If the sliding, hexagonal stone block covering the entrance is any indication, somebody would really prefer he didn’t. Sure enough, no sooner is the cowboy inside than the stone swings shut behind him, and a mummified Indian medicine man (Grefe’s usual makeup artist and corpse impersonator, Doug Hobart) clambers out of the stone sarcophagus in the center of the cave. (Who knew the Seminoles made stone sarcophagi? I sure didn’t.) The mummy transforms into the likeness of his living self (transforming into Bill Marcus while he’s at it), and bashes in the cowboy’s skull with a stone-headed mace. Then he relieves the slain cowboy of a bundle of scrolls on which someone has considerately inscribed the title and the opening credits.

A totally indeterminate amount of time later, Sam Gunther (Frank Weed, the animal handler for both Death Curse of Tartu and Grefe’s later Stanley) is canoeing into the same stretch of the Glades in company with a Seminole named Billy (also Bill Marcus; the dual casting wasn’t meant to do anything but save money, but I kind of like how it implies that Billy is descended from the mummy in the cave). Gunther was expecting Billy to be his guide throughout whatever he had planned on getting up to out here, but the Indian is adamant that he will do no more than drop Gunther off and tell somebody named Tyson where to find him. There’s an old Seminole burial ground hidden someplace in this particular patch of swamp, and it inevitably is said to be inhabited by evil spirits. Westernized, educated, 20th-century Native American or not, Billy has seen enough dead bodies hauled home from the area over the years to believe that his ancestors knew approximately what they were talking about. Billy also points out to Gunther the extraordinary silence of the hummock (Marcus and Weed bafflingly pronounce it “hammock”) where he and Sam have stopped. Both men know the Everglades well enough to recognize that something funny is going on when there isn’t a bird, frog, or singing insect to be heard for miles around. Be that as it may, though, Gunther will not be dissuaded from pitching his camp, and thus it is that he succumbs in short order to the titular death curse. This time, the deceased shaman does not wait for his grave to be violated directly. Turning himself into a ten-foot anaconda, he heads straight to Sam’s camp and does away with the interloper immediately after the latter uncovers some large stone artifact that we don’t get to see clearly.

The Tyson Sam and Billy were talking about turns out to be college archeology professor Ed Tyson (Fred Piñero, the star of Grefe’s long-lost “white slavery in Mexico” sleaze-fest, The Devil’s Sisters). Ed and his wife, Julie (Babette Sherill, also of The Devil’s Sisters), are on their way into the Everglades with four of his students, presumably to rendezvous with Sam Gunther and take advantage of his experience and expertise in locating old Indian sites. Tyson is a bit taken aback to see Billy at home instead of out in the swamp with Gunther, but he doesn’t push the issue too hard when Billy explains his reasons. All Ed asks is that Billy refrain from saying anything about Seminole death curses to Julie or the kids.

You can see why Tyson would want it hushed up, too. Julie, Johnny (Sherman Hayes), Cindy (Mayra Gomez Kemp), Tommy (Gary Holtz), and Joann (Maurice Stewart, whom the sharp-eyed might recognize as one of Sting of Death’s anonymous jiggling butts) are all the kind of people who recoil from virtually any sort of wildlife, and who just about shit their pants when confronted with anything dead. (My favorite line in the whole film: Ed demands of the students, “Now how are you people going to study archeology if you’re afraid of a little skull?” when they stumble upon a pike-mounted cranium that once decorated the lair of a certain were-jellyfish.) Just imagine how they’d react in the face of a dead guy who can turn himself into alligators and anacondas and whatnot! On the other hand, one really does have to side with the pack of fraidycats on the subject of what Sam Gunther’s absence from his campsite might imply for his or anyone else’s safety out there in the swamp. Nevertheless, Tyson is even more dismissive of sensible worries than he is of “superstitious,” “irrational” ones, and he quickly concocts the first in a series of increasingly unpersuasive innocent explanations for Gunther’s vanishing act.

We must conclude that the kids buy their professor’s bullshit, too, because otherwise there’d be just no way to account for what happens next. At about high noon on the first night of the Everglades camp-out (the day-for-night cinematography in Death Curse of Tartu is worse than anything you’ll see this side of The Eye Creatures), Johnny interrupts Ed in the midst of translating the carvings on that big stone thingy that Gunther discovered (and which the undead medicine man strangely did not reclaim after killing Sam), and mentions that he and the others want to go down to the riverbank and roast some marshmallows. No, really. And Tyson, despite having just deciphered enough of the carvings to know that they spell out the vow of a Seminole shaman named Tartu to rise from the dead in animal form and slaughter anyone who dares disturb his rest, and despite having also begun to entertain worries of his own about the missing Gunther, thinks nothing of sending the four students along their merry way unsupervised. Furthermore, there is every indication that Tyson commits this gross abdication of chaperonal responsibility for the sake of an opportunity to get groiny with Julie. What the fuck, Ed Tyson?!?! Johnny, Cindy, Tommy, and Joann are thinking groinally as well, marshmallows or no marshmallows, and they quickly discover a very interesting fact about Tartu: he does not approve of go-go dancing. Evidently awakened by the raucous teen hullabaloo down the hill from his cave, Tartu takes the form of— get this— a shark, and proceeds to gobble up Tommy and Cindy (who had inexplicably decided that going for a swim in the most disgusting water in the American South was a fine idea). This— finally!— convinces Ed that something untoward is going on around here, and a plan is hatched to send the fleet-footed Johnny off to summon rescue, while the others try to find Tartu’s grave and destroy him. They’ll have a little bit of help in the latter department from Tartu himself, who concluded his carven threat with a boast that only “Mother Nature” could defeat him. Awfully sporting of Tartu to put a “here’s how to stop me” clause right there in his own curse, even if it is kind of a vague one…

Sting of Death vanished almost without at trace when the initial double bill finished making the rounds, but Death Curse of Tartu had real legs. Frank Henenlotter recalls it playing on 42nd Street as late as 1976. That makes a certain amount of sense, for although Death Curse of Tartu is rather the less entertaining of the two films, it’s also far and away the more conventional. I mean, sure— I’d much rather watch a movie about a mad scientist who turns himself into a jellyfish than yet another take on the venerable “leave my tomb alone, goddamnit!” theme, but as I’ve observed in other contexts, catering to my tastes is frequently a lousy way to make money. What most saves Death Curse of Tartu from being just another shitty mummy movie with the setting shifted from Egypt to the Everglades is the utterly daft way in which Grefe employs Tartu’s shape-shifting ability. It’s amusing enough that Tartu can take the forms of animals that aren’t normally found in the Glades (like, say, stock-footage sharks), but the anaconda and Billy’s story about finding a dead man once who appeared to have been mauled by a tiger collectively prove that the shaman can turn himself into creatures that he should never even have heard of! I also really enjoyed the prologue’s unintended implication that Tartu killed Brad Grinter because he wanted to study the credits to his own movie, memorizing the names of the responsible parties for the sake of a more specifically targeted death curse in the future. And while it’s nowhere near as important an element in Death Curse of Tartu as it was in this movie’s original co-feature, the continuation of Sting of Death’s “monsters exterminate the beach party” angle is sure to be much appreciated by my fellow Frankie-and-Annette-hating grouches.

Meanwhile, there are a handful of things that Grefe did legitimately right here, intermingled with all the more conspicuous stuff that he botched to one degree or another. Frank Weed’s wrestling match with the anaconda is a very impressive set-piece; you can see at once why Grefe would cast the reptile-wrangler himself in the part of Sam Gunther, because any actor in his right mind would have resigned the instant he figured out what was being asked of him. Snake-lover though I am, you won’t see me inviting a constrictor that much bigger and stronger than I am to coil itself around my neck and upper body! The Everglades locations are once again very well and thoughtfully employed, to the extent that the swamp itself becomes easily the film’s most compelling character. And on a related note, Death Curse of Tartu, like its companion piece, features some generally excellent and occasionally even inspired cinematography and editing from longtime Grefe collaborator Julio C. Chavez. Chavez— and a lot of the other people Grefe worked with over the years, for that matter— had fled Cuba when Fidel Castro’s Communists took over in 1961, and although he had been a player of some note in his home country’s small and mostly inward-looking film industry, he spent his first few years in Miami working a succession of the shit jobs one typically associates with Hispanic immigrants to the United States. Grefe gave Chavez a chance to resume his real career, and the director was so pleased with Chavez’s work on Racing Fever that their partnership would continue until Grefe effectively retired from the movie business after 1977’s Whiskey Mountain. We primarily have Chavez to thank, I think, for the fact that Death Curse of Tartu’s within-scene pacing and fluidity are so much better than those of the film as a whole, and for the air of technical professionalism it puts forward even though most of the equipment used on the shoot was cheap, primitive, and sometimes flat-out improvised.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact