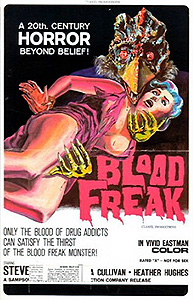

Blood Freak (1972) -****

Blood Freak (1972) -****

What is it with Floridian exploitation filmmakers and profoundly ridiculous forms of lycanthropy? First William Grefe gave the world its only known were-jellyfish in Sting of Death. Then Don Barton had another mad scientist turn himself into a were-catfish (or something like that, anyway) in The Blood Waters of Dr. Z. And now Brad Grinter and Steve Hawkes offer up what might be in practice the silliest of the bunch, the vampiric were-turkey of Blood Freak. Now I know what you’re thinking: there’s no way a were-turkey could possibly be sillier than a were-jellyfish. And if Blood Freak were merely a were-turkey movie, I’d have to agree. But my friends, Blood Freak is so much more than a cheap exploitation movie about a were-turkey. It’s a cheap born-again Christian exploitation movie about a drug-addicted were-turkey, as if an ABC After-School Special got into the Thunderbird and Oxycontin, and woke up five days later in the dumpster behind a whorehouse in New Orleans with no pants, no money, and half a dozen inexplicable tattoos.

Mind you, Herschel (co-creator Hawkes, who also acted in The Odd Triangle and The Sexiest Story Ever Told) doesn’t start out being a were-turkey. When we meet him, he’s just a young guy back from Vietnam with a screwed-up head, roaming the country on his motorbike in search of a place where he can fit in well enough to try putting his life back together on a halfway normal basis. While detouring into the great geographical cul-de-sac we call Florida, Herschel gives a lift to a hitchhiker by the improbably spot-on name of Angel (Heather Hughes, from Flesh Feast and Devil Rider!). This girl is on a giant Jesus trip, and while most of her friends find her incessant preaching well nigh insufferable, Herschel is at a point in his life where he’s ready to hear out anybody who claims access to The Answers. Angel can prattle on about the Holy Spirit all day long, so far as he’s concerned.

Yeah, well maybe a hippy pot party isn’t the best place to explore the limits of that willingness to listen. (Or maybe it is— some of the most stimulating theological discussions I’ve ever participated in happened in the company of stoned hippies.) At the very least, the particular party to which Angel brings her new pal is a distinctly hostile environment for That New Age Old Time Religion. Angel’s sister, Ann (Dana Cullivan), is doubly bummed to see her up to her old proselytizing tricks. I mean, where does that little goody two-shoes get off showing up with a guy hot enough to star in shitty Spanish Tarzan movies (as Hawkes did on two occasions), and then filling up his head with crap about chastity, purity, and abstinence from the pleasures of the flesh? It’s enough to make Ann want to lead Herschel into the worst damnation she can think of, just for spite’s sake. If she’s serious about that last part, one of the boys at the party might be able to help. Ann and her friends usually buy their grass from Guy (Larry Wright, from The Nest of the Cuckoo Birds), who deals in a far wider selection of pharmacological wares than this crowd habitually uses. If Ann felt like being truly nasty, he could set her up with something that’d make an addict out of Herschel in no time, Jesus or no Jesus. Ann accepts one of Guy’s laced joints as insurance against future contingencies.

Meanwhile, Angel introduces Herschel to her father, who owns the local turkey farm, and could use a big, strong guy like the troubled vet to help out with the 10,000 odd jobs that arise in the course of raising, slaughtering, and butchering poultry. Rather surprisingly, given the scale of this operation, the family farm has a professionally equipped biochemistry lab on the premises, with two full-time scientists on staff. Actually, “scientists” might be stretching the truth just a little. From the looks of these guys, I’m betting most of their hands-on experience with organic chemistry comes from cooking meth for Guy’s supplier. Be that as it may, it’s the turkeys that Angel’s dad is paying them to drug. He wants bigger and faster-growing birds, and the two lab-louts are apparently pretty close to a breakthrough. They’ve got a feed supplement that does indeed accelerate growth, but they’re not sure yet whether birds treated with it will yield meat fit for human consumption. If Herschel would like to earn a few extra bucks on the side (or to score a few ounces of weed— either way is cool), he could be a big help to the farm by eating some of those specially treated turkeys.

Herschel would indeed like to earn a few extra bucks. And Ann, for her part, eventually finds a way to make him toke up on Guy’s dusted devil-weed— she spins it for him as a question of courage. Hmm… Pot with a mysterious, secret additive; turkey that’s been exposed to a mysterious, secret dietary supplement… Sound like drug interaction to you? And what an interaction it is! By the time the two chemicals he’s been hornswoggled into ingesting have finished their little minuet through Herschel’s metabolism, he’s reduced to a helpless heap of twitches and spasms, to the point where the turkey farm’s meth-cookers feel compelled to dump him in a secluded field, hoping nobody notices until his bones are good and dry. And that’s not the worst of it, either. The worst of it, as I’m sure you already realize, is that when Herschel emerges from his seizure, he becomes a turkey-headed monstrosity with an addiction that only human blood can slake! Now that’s weird, but isn’t half as weird as how Ann and her friends react to his transformation. True to their “do your own thing,” “let your freak flag fly” convictions, they treat Herschel’s metamorphosis like it’s no big deal! (Angel, you will note, effectively vanishes from the story at this point. Herschel apparently thinks a nice girl like her shouldn’t have to deal with problems like his.) Ann even remains willing as ever to have sex with him, although she does worry aloud at one point about the prospects for an interspecies marriage. Still, the hippies do recognize that Herschel might not actually want to be a blood-hungry were-turkey (it’s no use just asking him, since all he can say anymore is “gobblegobble”), and with that in mind, they start looking for Guy, reasonably concluding that his laced pot might have something to do with the situation. That blood-drinking thing is going to be a real problem for everybody, though— or it would be, were everything we’ve seen since Herschel lapsed into his seizure not merely a hallucination he’s been having under the dual influence of the two unknown drugs.

Now I’m sure we can all agree that All Just a Dream endings suck, and have sucked since at least 1920, when J. Charles Haydon used one in his incoherent and ridiculous version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde for Louis Meyer. Blood Freak is different, though. What sets this movie apart is not so much that its version of the cliché is any less annoying, but rather that Grinter and Hawkes handle the reveal in a way that perfectly plays up their film’s most madly absurd aspect. You see, it’s misleading to call what happens here an All Just a Dream ending, because it doesn’t actually end the film when Herschel is discovered in his psychedelic state by Angel and Ann’s father. To explain what happens properly, I’ll have to backtrack a bit, because I haven’t yet said anything about Blood Freak’s narrator segments. At irregular intervals throughout the movie, the action is put on hold so that Grinter, looking like somebody’s drunken uncle in the throes of a mid-life crisis, trying to regain his youth by glomming onto the next generation’s version of edgy cool, and getting it conspicuously not quite right, can pontificate into the camera from the cheaply paneled confines of his rec room. The tone of these interludes is a different species of counterfeit cool— that of the non-denominational youth pastor trying much too hard to convince the unimpressed teenage offspring of his supervisor’s flock that church is a happenin’ place, and Jesus a swingin’ cat. That is, Grinter casts himself as the voice of righteous wisdom, warning the viewer away from the path of vice that Ann is eagerly leading Herschel down, so that when two thirds of the movie are revealed never to have happened, it becomes a chance for the characters to take back their fatal missteps. It wasn’t for nothing, in other words, that I referenced the J. Charles Haydon version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde at the beginning of the paragraph.

Again, though, Blood Freak is even weirder than it looks, and that extra weirdness explains why it carries on so long after we find out that there’s no such thing as a were-turkey after all. This may be a didactic horror story, but think about who the real sinners are. Herschel— and Grinter’s omniscient interjections are quite clear on this— does nothing worse of his own volition than to yield to a concerted campaign of temptation. It makes no sense to end with him getting a second chance to mend his evil ways, because his ways were never notably evil to begin with. The people who need straightening out here are Angel’s family and friends— Ann and the other hippies with their doping and promiscuity, and the girls’ father with his bad business ethics and his tampering in God’s… er… animal husbandry? Whatever. The point is, Herschel’s narrow escape is their moral wake-up call more than his. That’s why it can’t be a simple matter of Herschel coming to in that field and saying, “Whoo! What a terrible nightmare! I sure have learned my lesson…” That’s why Dad has to get worried about the new hand’s disappearance, extract from the lab-louts directions to where they dumped him, and hurry, chastened, to the rescue. Not knowing about Guy’s poison pot, he must take upon himself the responsibility for Herschell’s condition, and heed henceforth the words of the prophet: Poultry growth-rates are mine, sayeth the Lord. Ann and her friends, meanwhile, must hear from Angel about the state Herschel is in, and knowing nothing of the doctored turkey, must renounce their counterculture hedonism. To put it in terms of a different horror morality tale, Herschel may be the one who got visited by the ghosts, but he’s really just Tiny Tim in this Christmas Carol.

Amazingly, I can find no indication that Blood Freak is anything less than sincere about its intentions to inspire the audience to greater rectitude. Despite its troubled production history, I’ve uncovered no story equivalent to those about all the hassle Ed Wood was put through by the church group that semi-wittingly fronted most of the money for Plan 9 from Outer Space. No source I’ve consulted (although admittedly there aren’t exactly whole libraries of material available on Blood Freak) has mentioned any distributor with an axe to grind, proclaiming that no were-turkey flick would pass through his hands on the way to the drive-in unless it encouraged good Christian morals. That’s all the more remarkable because Brad Grinter and Steve Hawkes were not the sort of people I’d normally expect to serve up sermons alongside their blood-drinking poultry monsters. Hawkes, as I mentioned, played Tarzan in a couple of Spanish cheapies shot in Florida (which was easier to pass off as “the jungle” than anyplace in Iberia), and his involvement in Blood Freak was the unlikely end result of a pyrotechnics accident that badly burned him and his costar, Kitty Swan, during the production of Tarzan and the Brown Prince. Evidently the Spanish producers were operating without insurance (or at any rate, with grossly inadequate insurance), and rightly fearing a lawsuit, they fled to South America to complete the movie without the injured actors. Hawkes and Swan were left to pay their own hospital bills, and Blood Freak was intended to be Hawkes’s way of doing so. But before his swarthy complexion and powerful physique landed him the Tarzan gig, Hawkes had appeared in some of Joe Sarno’s pre-hardcore porn films, and indeed he closed out the 60’s by directing a roughie of his own under the name Gene Martyn. That was The Walls Have Eyes, in which he also played the starring role. Nor was he done with smut as the new decade dawned, for his next project after Blood Freak was the incredibly obscure The Sexiest Story Ever Told. Grinter, meanwhile, seems an even less likely purveyor of so crudely moralistic a fright film. A lifestyle nudist, Grinter made several very late, very weird contributions to the numbingly vast corpus of nudist camp cinema, including The Sweet Bird of Aquarius (which extols the virtues of partner-swapping alongside nudism), Barely Proper (the Inherit the Wind of nudist camp exploitation), and Never the Twain (in which— are you ready for this?— the hero is possessed by the spirit of Mark Twain during the 1974 Miss Nude World Pageant).

Grinter’s naturism may explain the seeming contradiction in Blood Freak between the film’s implicit sympathy for the concept of a counterculture (the destructive effects of Herschel’s military service turn into a pretty big issue during his post-drugging recovery, for example) and its explicit condemnation of the actual counterculture’s disregard for bodily purity. It might also account for the movie’s strongly negative attitude toward putting synthetic chemicals in things. The 70’s were a big decade for monsters spawned by pollution, of course, but I’m having a hard time thinking of other contemporary horror or sci-fi movies that specifically finger food and drug additives as a monster-making agent, let alone ones that emphasize the idea enough to suggest a conscious polemical intent. Those are about the only things in Blood Freak for which I can propose an explanation or accounting, however. The rest I can only marvel at, and invite you to do the same.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact