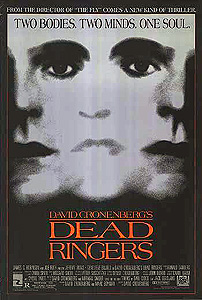

Dead Ringers (1988) *****

Dead Ringers (1988) *****

While reviewing The Brood, I remarked that David Cronenberg seems to have designed it, whether consciously or not, to play upon uniquely masculine fears. Well, with Dead Ringers, Cronenberg demonstrates that he is equally capable of exploiting distinctively feminine phobic pressure points. Though continuing with his favorite theme of medical horror, in this film Cronenberg delves into the little-explored field of specifically gynecological horror, while simultaneously giving a truly savage working-over to practically all of every woman’s most deep-rooted psychosexual worries. From genital mutilation to infertility to the gross betrayal of nearly every sort of trust, there’s scarcely a single thing that keeps women up at night which Dead Ringers doesn’t latch onto and shake with the vicious tenacity of an enraged bulldog.

At the center of the story are two of the most twisted characters Cronenberg has ever portrayed. (We can’t give him credit for inventing them, however. That distinction belongs to Bari Wood and Jack Geasland, whose novel, Twins, serves as the basis for the film.) Identical twin brothers Elliot and Beverly Mantle (both played as adults by Jeremy Irons, who sure did slip a ways between Dead Ringers and movies like Dungeons & Dragons and the Time Machine remake) are highly intelligent, somewhat withdrawn kids with a profound interest in both female sexuality and medical science. Like many pairs of twins, the Mantle boys are exceedingly close; as children, they invariably pursue their curious hobbies as a team, and when their conspicuous intellectual talents carry them from Toronto to Oxford University’s medical program, their partnership persists at each step of the way. Very early on, the Mantles make a name for themselves as innovative thinkers. When they are not satisfied with the standard tools and practices of their discipline, they don’t hesitate to invent their own, even in the face of undisguised disapproval from their instructors. Their persistence pays dividends, too. While they’re still undergraduates, Elliot and Beverly develop a new form of surgical retractor that almost immediately becomes the new standard in the profession. By 1988, the Mantles are back in Toronto with a thriving private practice in obstetrics and gynecology and a prestigious series of research engagements. Elliot, meanwhile, has in addition a teaching post at one of the city’s most important hospitals. These days, the partnership between the brothers is more specialized than it had been, with Elliot standing as the businessman and the public face of the company, while Beverly takes the lead in treating the patients and conducting the research.

The reputation of Mantle Inc. is such that they attract some pretty high-rolling patients. One of these is an actress named Claire Niveau (Genevičve Bujold, from Coma and Obsession), who is nearly desperate to have children now that she’s creeping slowly up on middle age. She’s been to one doctor after another, she’s gotten herself started on hormone treatments, and she’s been, in her own words, “extremely promiscuous” while taking no contraceptive precautions whatsoever. None of it has done the slightest bit of good, and Beverly Mantle has no doubt at all about why. Niveau’s reproductive anatomy is put together all wrong, her uterus divided into three chambers much too small to accommodate a fetus, each with its own separate cervix. Simply put, she’s a mutant, and there’s nothing that even the celebrated Mantle Brothers can do to make her conceive.

Actually, since Claire doesn’t know that Elliot exists, maybe I should rephrase that to eliminate the reference to “brothers.” In fact, that evening, when Elliot takes Claire out to dinner to discuss her case, and then ends up following her back to her place and seducing her, Niveau is under the impression that she’s still with Bev! What’s more, this sort of thing is pretty much standard operating procedure for the Mantles. Since nobody can tell the two of them apart anyway, they’ve found it easy enough to impersonate each other on a routine basis and thus share their social lives as completely as they do their research, their practice, and their apartment. But as it happens, Claire Niveau is the woman who is destined to undo not just this rather warped arrangement, but ultimately everything else in the twins’ lives as well. When Elliot passes Claire along to his brother the next day, Bev falls for her (although it’s going to be a while before Beverly himself figures that out), and is almost instantly struck by an irresistible desire to have her all to himself. Elliot sneaks in a few rendezvous here and there (always presenting himself as Beverly when he does it), but for the most part, Bev gets what he wants. However, even a few rendezvous with Elliot here and there are enough to make Claire notice the difference, and when a friend of hers (Shirley Douglas, of Really Weird Tales) mentions in passing that Beverly has an identical twin, she suddenly gets the picture. Claire pressures Bev into arranging for her to have dinner with both of the Mantle boys, at which point she lets the two of them know just what she thinks of the situation: “You know, I’ve been around a lot, and I thought I’d seen some pretty creepy shit, but this is the most disgusting thing that’s ever happened to me!”

Beverly doesn’t take the breakup nearly as well as Elliot. Elliot, after all, had no emotional investment in Claire, and indeed regarded her as a destabilizing influence on his relationship with his brother. But of equal importance, Beverly is doubly ill-equipped to deal with the loss because he picked up a slew of Claire Niveau’s drug habits while he was seeing her. Beyond that, Elliot has just been offered a promotion he’s been angling for since who knows when, with the result that he’s henceforth going to have a lot less time for stuff like making sure Bev doesn’t dope his way to the ruination of Mantle Inc. While Elliot is busy with his new professorship and his schmoozing for grant money and his own sort-of girlfriend (Heidi von Palleske, from Cybercity and 2103: The Deadly Wake)— in whom he tries without success to interest his brother— Bev gets himself hooked on heroin and goes so far off the deep end that he starts seeing “mutations” behind every set of labia he sticks his speculum through. Bev eventually hires metalwork sculptor Anders Wolleck (Stephen Lack, of Scanners) to build him an array of terrifying new instruments with which to operate on his “deformed” patients, and all hell threatens to break loose. As bad as all that is, though, it’s really only the beginning.

When it comes to sheer psychosexual ooginess, there’s a fair chance that Dead Ringers is David Cronenberg’s magnum opus— although I should qualify that by admitting that I have yet to see Crash. I think what impresses me most about it is the seemingly effortless way in which Cronenberg adopts what I would call a feminine perspective on the story, even though the key female character is entirely out of sight for much of the film. Dead Ringers is unquestionably about the Mantle Brothers, but it looks at them, if not through Claire Niveau’s eyes precisely, then through the eyes Claire Niveau has reason to wish she had. We know that Beverly and Elliot are trading off long before she does, we can see how unhealthy the bond between the Mantles is before Claire even understands that the bond exists, and when Claire and Beverly eventually resume seeing each other, we’ve seen ample evidence to which she is not privy that says such a reconciliation is an almost unimaginably bad idea. Meanwhile, we are given plenty of opportunities to contemplate the fact that, while the Mantles may be the best in the business from a technical perspective, ethically speaking, they’ve got to be the worst gynecologists in the world. At one point, we see Elliot giving some prospective donors a presentation on fallopian tube replacement mere moments after hearing him tell his reclusive brother that “One of the great things about our business is that you don’t have to go out to meet beautiful women.” When Beverly’s downward spiral of addiction and mental collapse finally lands him and his twin in hot water (and under grandly appalling circumstances, I might add), one marvels at the lack of official vigilance which permitted them to get away with everything short of that final climactic outrage.

Another thing you simply have to marvel at is Cronenberg’s success in crafting so skin-crawlingly effective a gross-out movie while using hardly any of the intensely explicit gore for which he had been notorious up to then. Except for a nightmare sequence early on, which sets up the Siamese twin theme that will become increasingly important as the film progresses (and which rivals the maggot-birth scene from The Fly for its ability to induce actual nausea), Dead Ringers is almost completely devoid of onscreen grue. Nevertheless, I defy anybody not to feel a twinge of revulsion when Beverly shows Anders Wolleck the blueprint for what looks like a macabre cross between a scalpel, a skeleton finger, and a bug’s leg, and then tells him, “They’re gynecological instruments for working on mutant women.” What Cronenberg gives us is a new corollary to the oft-invoked principle that a well-exercised imagination can frequently scare its owner far more effectively than a special effects artisan— it turns out a filmmaker who really knows what he’s doing can achieve matchless levels of pit-of-the-stomach disgust by implication and innuendo as well.

Even so, it is unlikely that Cronenberg would have succeeded as brilliantly as he did with Dead Ringers had it not been for some truly first-rate casting. Jeremy Irons turns in an awesome performance— two awesome performances, really. Both Beverly and Elliot Mantle seem entirely real, entirely living, and while it isn’t always possible to tell them apart with any certainty, I get a strong sense that the occasional ambiguity was deliberate. We are dealing, let us not forget, with two characters who habitually take each other’s places, and who are gradually shown to be something very much like complimentary aspects of a single, but bifurcated, identity. Irons is equally at ease with Elliot’s shallow charm and amoral efficiency on the one hand, and with Beverly’s awkward neediness and emotional vulnerability on the other. Furthermore, Irons puts across in no uncertain terms the vital point that Elliot’s love for his twin is the one profound and genuine thing about him, even if the form that love takes often makes it all but unrecognizable to anybody but the brothers themselves. Despite all we’ve seen by that point, it’s still a strongly affecting moment when Elliot answers the dope-sick Beverly’s question about why he doesn’t just cut his losses and get on with own life by asking Bev to recall the story of how Chang and Eng, the conjoined twins from Siam who gave the condition its popular name, died. It’s a considerable achievement to take a character as loathsome as Elliot Mantle and make him also sympathetic without diminishing that loathsomeness in the slightest degree.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact