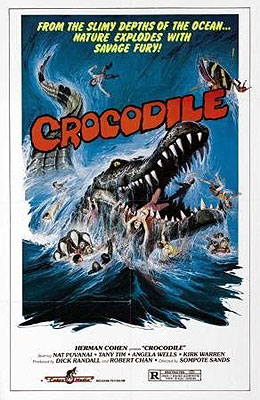

Crocodile / Giant Crocodile: Bloody Destroyer / Chorakhe (1979/1981) -**Ĺ

Crocodile / Giant Crocodile: Bloody Destroyer / Chorakhe (1979/1981) -**Ĺ

About 26 minutes into Crocodile, Dr. Anthony Akom (Nat Puvanai, from Hands of Death and Ghost Hotel), the closest thing this movie has to a protagonist, goes to the ophthalmologist to be fitted for contact lenses. Itís a very weird scene, seemingly intended to convey a great deal more meaning than is evident on its faceó and not merely because the newspaper on which Akom tests out his improved visual acuity provides him with the pivotal clue to a mystery that has been consuming his life of late. No, it seems as though the change in Akomís optical equipment is itself supposed to symbolizeÖ well, something. And yet in the very next scene, his familiar Coke-bottle glasses are right back in place, as if his curiously emphatic visit to the eye doctor had never happened. Then a few scenes after that, Akom accidentally breaks those glasses in a second heavily overemphasized moment of apparent opaque symbolism. Thatís when I understood. If Crocodile had been strangely scattershot and directionless so far, almost as if it had been cut apart at some point and then reassembled in the wrong order, it was because thatís literally what had happened to it. Indeed, as I discovered later, that fate had befallen it to one extent or another at least twice, and possibly as many as three times. No wonder this movie makes almost no goddamned sense!

Before one can attempt to understand Crocodile, it is necessary at least to know about Crocodile Fangs. The latter film was a South Korean-Thai coproduction, directed by Won-Se Lee and featuring special effects sequences created by Thailandís most notorious cinematic weirdo, Sompote Sands. It was released in South Korea in 1978, and may also have played in its other country of origin at the same time; subsequent developments make this part of the story extremely difficult to untangle for people without functional access to Thai- or Korean-language sources. Indeed, subsequent developments make it difficult for such people to say anything about Crocodile Fangs without having actually seen it, so weíll just have to table the subject until the bootleg copy I ordered online a few days ago arrives in my mailbox. What really matters for our present purposes is that the movie somehow came to the attention of globetrotting trashfilm impresario Dick Randall, who was splitting his time between Rome and Hong Kong in those days, producing movies like Escape from Womenís Prison and The Clones of Bruce Lee.

Randall must have figured that an Asian killer croc flick would be a smart pickup, getting him in on the still-fashionable Mother Natureís Revenge action dirt cheap. Once he saw Crocodile Fangs for himself, though, he decided it didnít quite suit his purposes after all. Still, the asking price was so low that Randall bought the overseas rights anyway. Then he evidently hired Sompote Sands to recut, reshoot, and otherwise transform the film into something more in tune with Western tastesó and at this point I simply have to ask whether Randall had seen any of the films that Sands had directed himself. I mean, hiring the director of Magic Lizard and Hanuman and the Seven Ultramen to make a movie marketable in the West is like hiring a blind man to paint your picture! Regardless, no one should be surprised that the Frankenfilm Sands turned in the following year wasnít exactly what Randall was looking for, either. He released it in Southeast Asia just the same, on the theory that Sands knew local audiences better than he did, but before sending what he was now calling Crocodile out to face the rest of the world, Randall had it recut yet again, along with commissioning still another round of minor reshoots. Most international markets got that version, but it evidently wasnít until 1981 that a buyer was found for the US rights. That buyer was former American International Pictures luminary Herman Cohen, who made changes of his own by trimming the sleaziest bits of Randallís cut. Cohenís version is the one I saw, and the one Iíll mostly be talking about from here on out.

By far the most unexpected thing about Crocodile is that itís a kaiju film as well as a Jaws rip-off. It announces that dual identity right up front, too, by starting with a recut version of the climactic typhoon scene from Sandsís rural poverty melodrama, Land of Grief, and then blaming the storm on nuclear weapons experiments. I donít know how the footage played in its original context, but here itís a dead ringer for the typhoon that strikes Odo Island in Godzilla: King of the Monsters. And as we see soon thereafter, deadly weather isnít the only nasty thing unleashed by those H-bomb tests, either. A saltwater crocodile got caught in the radioactive fallout, and has grown to mammoth size as a consequence. Every three days or thereabouts, this monster croc makes its presence felt somewhere along the Thai seacoast, killing swimmers (but usually spitting out their severed arms, oddly enough), devouring livestock, and occasionally laying entire villages and towns to waste. Perhaps as is only to be expected in a country impoverished by centuries of Western colonialism, thereís no sign of the military response that one usually sees in movies about giant monstersó only the hapless efforts of one obviously outmatched police inspector, whose final defeat comes when the crocodile swims away with the humongous leg-hold trap that was supposed to restrain it, tangling up the inspectorís men in the chain meant to anchor the device to the harbor floor and drowning the lot of them.

Among the crocodileís human victims are the loved ones of two doctors, the aforementioned Anthony Akom and his friend and colleague, John Strong (Min Oo). Strong loses his new bride, Linda (Eunee Wang, hiding behind the extremely plausible pseudonym, ďAngela WellsĒ), while Akom loses not only his shrewish wife, Angela (Ni Tien, from Black Magic and Cleopatra Jones and the Casino of Gold, whose ďTany TimĒ alias is somehow even funnier than Eunee Wangís), and pre-teen daughter, Anne (Nancy Wong, maybe?). Both men plunge into a pit of despair in the aftermath, not least because neither one of them was around when their womenfolk were eaten. Furthermore, no one at this phase of the story even knows whatís causing the rash of horrid aquatic deaths, so the doctors are denied even the dubious comfort of a specific target for their anger. As soon as the giant reptile reveals itself, however, Akom and Strong dedicate themselves to its destruction. Obviously theyíre going to need someone to play Quint to their Brody and Hooper, which is where an eccentric fisherman by the name of Tanaka Lujan comes in. (The credits say this is Kirk Warrenó ha!ó but at least some sources identify Tanaka as Thai action-movie regular Manop Aswathep, whom we may see again if I ever get a chance to review The Tiger Devil.) Tanaka saw the croc himself from the deck of his boat while at work, so he needs very little persuasion when the doctors come to him for help catching and killing the thing. The crocodile hunters also acquire an unwanted hanger-on soon after setting out for what Akom believes to be the most likely site for the monsterís next attack, based on his analysis of its movements so far. Just barely has Tanaka taken up a holding position in the bay in question when a reporter called Peter (Robert Chan Law-Bat, who evidently was also involved in the production side of Crocodile, Crocodile Fangs, or both) rides out to meet them in a motorized canoe, and asks to be taken aboard. After all, what newspaper, magazine, or TV station could resist a story like two personally motivated would-be monster-slayers taking it upon themselves to do what the Proper Authorities cannot? And at least if youíre watching either of the export cuts, Akom will ultimately have reason to be glad the little schmuck came along.

You wonít have to watch Crocodile for very long to notice the bewildering variability of the monsterís apparent size from one scene to the next. Most of the time, it looks like itís supposed to be some thirty to sixty feet long, with the full-sized puppet of its head and forequarters suggesting the lower end of that range, and the large-scale miniature used for some of the swimming scenes usually suggesting the upper. But throughout the film, the monster is also represented by an entire menagerie of real Siamese and/or saltwater crocodiles, and all bets are off when one of them is on the screen. Depending on the size of the actual animal, the scale of the miniatures associated with it, and the unpredictable effectiveness of Sandsís forced-perspective and editing trickery, the killer croc in these segments can seem to be any size from a completely unremarkable fifteen feet (as in the scene with the monkey eating crabs while perched atop its tail as it rests in a tidal swamp) to at least ten times that (as when it wades ashore to eat a water buffalo, or on either of the occasions when it swims up a canal to destroy a human settlement). Iím not prepared to attribute that wild variation entirely to careless incompetence, though, because of the extraordinary amount of cutting and pasting that Crocodile endured on its way to my eyeballs. It may be that the monster was originally supposed to grow steadily from the moment of its irradiation, and that that progression has been obscured because no two of the crocodileís scenes are presented in the correct order anymore. For example, those who have seen the Sands cut report that the two canal attacks were originally one extremely long sequence, and that the water buffalo scene (one of the bits that rightly earned Crocodile a condemnation from the Humane Society) occurs much earlier in that version than in the Randall and Cohen cuts. I doubt that all the inconsistencies can be accounted for that way even so, but it might suffice to clear up the most absurd ones.

The same extenuating circumstances might be pled for a lot of Crocodileís defects, for that matter. Maybe in the Thai cut, the monster attacks donít occur with such metronomic regularity as to interfere with the development of the human story. Maybe with all the scenes in their intended order, it isnít so hard to figure out which characters weíre supposed to be paying attention to until half of them are already dead. Iíve read that some prior incarnation of this film (be it the Sands cut, Crocodile Fangs, or both) devoted a lot more time to Akom and Strong trying unsuccessfully to cope with their trauma by less drastic means than picking a fight with a man-eating reptile, so perhaps their transformation into low-grade action heroes originally wasnít quite as implausible. And I similarly have it on good authority that the final round of reshoots altered the climax to the extent of changing which character delivers the killing stroke to the monster croc. If nothing else, that must have had a major effect on the filmís thematic integrity. I expect Sompote Sands will still have a lot to answer for if I ever see his cut of Crocodile, but my instinct is to blame Dick Randall first for the almost incomprehensible train wreck that is this version.

That said, some of us enjoy the occasional incomprehensible train wreck, and when thatís the kind of mood youíre in, Crocodile delivers. On top of everything Iíve already described, youíll get Manop Aswathepís (or whoeverís) performance as Tanaka, in which Quint is reinterpreted as a Yukio Mishima-like Asian leather daddy. Youíll get Akomís trip to the morgue, in which you wonít be able to tell until the end of the film whether heís just moping morbidly over the scattered bits and pieces that are all that remains of his family, or whether heís stealing cadaver parts to use as crocodile bait on his big revenge trip. Youíll meet an old herpetologist who seems genuinely surprised at the possibility of crocodiles surviving in salt water, even though exactly such animals are found in all the seas between Sri Lanka and Vanuatu. Most of all, youíll get the inimitable combination of ambition and ineptitude that characterizes any film on which Sompote Sands plied his trade as an effects artist. Just be aware that this is very much not a movie for animal lovers; frankly, Iím shocked that Sands didnít end it by blowing up a real crocodile carcass!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact