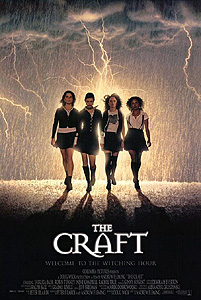

The Craft (1996) **

The Craft (1996) **

It’s funny. At the time, it seemed to me that the 1990’s were far too fragmented, culturally speaking, for the decade to have any coherent personality, and for the most part, I have little firm sense of what those years were “about” even now. So the last thing I expected when I saw that The Craft was coming on cable TV in a few minutes, and decided that I kind of wanted to see it again, was to be bowled over by its sheer, overwhelming 90’s-ness. To an even greater extent than usual, writing this review is going to be an exercise in sorting out what it was about the movie that I reacted to, because I think that if I kick The Craft around long enough, it might lead me toward a way to articulate some ideas about the era of my youth that had never properly solidified even after all these years.

The “craft” of the title is, of course, witchcraft. Its principal practitioners here are Nancy Downs (Fairuza Balk, from Grindstone Road and American History X) and her friends, Bonnie (Neve Campbell, of Scream and The Dark) and Rochelle (Embrace of the Vampire’s Rachel True). All three girls are outcasts at their Los Angeles Catholic high school, but it was apparently not their interest in the occult that made them so. Nancy has an extremely troubled home life, for starters. Her mother (Helen Shaver, from Starship Invasions and The Amityville Horror) is a drunk, and Mom’s boyfriend, Ray (John Kapelos, of Weird Science and The Relic), is a lout who takes far more avid notice of Nancy’s off-kilter beauty than is consistent with his quasi-parental role. The family also lives close enough to the poverty line that it doesn’t seem like they should be able to afford Nancy’s tuition, but maybe she has a scholarship. In any case, it’s no fun being the school hillbilly, and thus no surprise that Nancy would project the most confrontational goth persona that she can contrive— if she’s going to be ostracized anyway, it might as well be for something of her own choosing. Rochelle’s main problem is demographic. She is to all appearances the only black student in the entire school, and racist prom queen-type Laura Lizzie (Christine Taylor, from Night of the Demons 2 and Campfire Tales) has made it her mission in life to keep Rochelle always as miserable as possible. As for Bonnie, she was horribly burned at some point in the past, and much of her body from the neck down is covered in thick, rugose scars— and we all know how forgiving juveniless are of disfigurement, don’t we? As is the way of socially leprous teenagers, Nancy, Bonnie, and Rochelle became friends essentially for survival, and in the black arts, Nancy found for them something from which they could draw an illusion of power. Naturally an illusion is all it is, however, and although the three self-proclaimed witches diligently practice their rites, spells, and invocations, their lives remain as totally untouched by the numinous as that of any disaffected adolescent. Nancy contends that their failures stem from want of a fourth member in their circle (the school of conjuring they favor leans heavily on the Hellenistic concept of four as a mystically significant number), but, well… she would, right? After all, it’s far less traumatic that way than to admit that she and her friends are just three unhappy kids hunting desperately for a source of influence over a hostile world.

Or at any rate, that’s where the situation stands until Sarah Bailey (Robin Tunney, from End of Days and Supernova) moves to LA, and her folks enroll her in the same school as Nancy’s coven. Sarah doesn’t realize this, because her biological mother died giving birth to her, but the first Mrs. Bailey was a real witch— someone with an innate affinity for communication with the spirit world and a consequent ability to channel its forces into the material realm. For that matter, Sarah’s father (The Hunger’s Cliff De Young, who had impersonated Barry Bostwick a decade and a half earlier in Shock Treatment) and stepmother (Jeanine Jackson, of Red Dragon) know nothing about that either, and their ignorance is most unfortunate for Sarah. The girl inherited her mother’s gifts, you see, and if Mom were around, there would be someone to explain to Sarah what’s going on when, for example, a wish for rain seems to cause the pipes to burst in her bedroom wall. As it is, Sarah has little choice but to vacillate between thinking she must be crazy and fearing the unintended consequences of her every stray thought and passing whim. You’re beginning to see where this is going, aren’t you?

Sarah has a leg up on Nancy and her friends even despite being a low-wattage Carrie White, because she can at least pass for normal most of the time, and she’s much more conventionally pretty than they are. Presumably it’s the latter fact that captures the interest of senior class football hero Chris Hooker (Skeet Ulrich, also in Scream), and leads him to initiate contact with the new girl in class. Chris seems a nice enough lad by jock standards, but there are nevertheless a few red flags that Sarah would be wise to heed. First of all, his best friends, Trey (Nathaniel Marston) and Mitt (Breckin Meyer, of Escape from L.A. and Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightnare), are class-A prickweasels, and beyond that, Chris makes a point of warning Sarah away from the witches by giving her a crash course in all the malicious gossip about them that is currently circulating through the student body. Nevertheless, Sarah likes Chris, maybe enough to be interested in dating him. Meanwhile, Bonnie takes notice of the new girl as well, and more importantly, she takes notice of the small, strange things that always seem to happen when Sarah is around. Almost like she has magic inside her, or something.

Nancy initially balks at the suggestion that Sarah could be the person they’re looking for to complete the circle, but her sidekicks wear down her resistance soon enough. For her part, Sarah is a little puzzled by the abrupt reversal of the witches’ collective attitude towards her (Nancy had always been downright rude before), but she appreciates the chance to make a few friends in her new town. Besides, the owner of the boutique where the girls shoplift the paraphernalia for their witchcraft (Assumpta Serna) is interesting. No cynic out to fleece the local hippies, Lirio genuinely believes in the efficacy of the books, charms, potions, and other magical doodads she peddles, and more importantly, she recognizes at first sight that there’s something unusual about Sarah. Like Bonnie, Lirio is of the opinion that Sarah is a “natural witch,” but she seems to have a clearer idea of what that might mean than any of the girls. She could make a valuable mentor if approached correctly. In any case, there’s no denying that the addition of Sarah to the coven is having the desired effect. Levitating each other and casting glamours to change their apparent eye and hair colors are only the beginning. Once the girls have a bit of practice under their belts, they start to turn their newfound abilities toward fixing what’s wrong with their lives. Invoking the power of a divinity called Manon (Nancy puts it thusly: “If God and the Devil were playing football against each other, Manon would be the stadium”), Bonnie wishes for a magical boost to the experimental gene-therapy treatments she’s about to undergo in the hope of repairing her ravaged skin; Rochelle wishes for strength to bear up under other people’s hatred, as if she were a hard, reflective substance from which a bigot’s negative energy would harmlessly rebound; and Sarah wishes for love, both from herself and from Chris Hooker— who, as she just discovered in the most humiliating way, has merely been playing her. What about Nancy, you ask? Nancy wishes for power. Not power to accomplish some concrete goal, you understand— just power pure and simple, and lots of it.

All four girls get their wishes eventually, and for a while at least, it’s pretty great. But as Lirio warns Sarah (and as she would have warned the others if they’d let her), magic— even the magic of Manon— doesn’t just make stuff happen. There are costs to be borne, tradeoffs to be made, balances to be preserved. Consider Rochelle’s spiritual reflectivity. The hatred that now bounces off of her has to go somewhere, and while I certainly won’t be shedding any tears for Laura Lizzie when her repulsed bigotry starts acting on her like a moderate case of radiation poisoning, it does trouble Rochelle to see her nemesis losing her hair by the handful. Rochelle wished no harm even to Laura; she merely wanted to take away Laura’s power to harm her. Meanwhile, beauty makes a narcissist of Bonnie, bringing out in her unsuspected depths of shallowness. Sarah’s unintended consequences are the most complex, as is only to be expected when someone is fool enough to mess around with love. The truth is, she no longer really wanted to date Chris when she placed him under her spell. She just wanted to force Mr. Seduce-and-Destroy to experience the vulnerability that comes along with having feelings for someone. But what she’s done instead is to turn him into a stalker, a potential danger both to himself and to her. Sarah gets more bad news when she goes to Lirio seeking a way to undo what she and her friends have done: there isn’t one. Good and evil, right and wrong, prosperity and suffering— these are all human concerns. Manon, like the cosmos he personifies, just is; he has no vested interest in morality one way or the other, and his power, once deployed toward a certain end, can no more be recalled than a match can be unlit or a bullet unfired. Chris’s obsession, Bonnie’s descent into egomania, and Laura’s toxic reaction to her own vileness will simply have to run their courses. The most troubling implications of these tidings concern Nancy, however. Take someone with a naturally domineering personality, fill her with resentment, hostility, and rage, and then impart to her the power to distort the fabric of reality at will… It’s pretty much the recipe for a supervillain, isn’t it? Sarah, Bonnie, and Rochelle never gave any forethought to how their magic could inflict harm, but for Nancy that was always a large part of the point. And if, as seems increasingly likely, it’s going to come down to a confrontation between her and Sarah, which side to you think the two lesser witches are going to take?

There are two respects in which The Craft confirms my vague, old memories of it. First, Fairuza Balk was ridiculously hot back in the late 1990’s; and second, it isn’t a very good film. Acting ranges from fair to abysmal, often within a single cast-member’s performance. Balk in particular commits some atrocious scenery-chewing crimes, despite also contributing most of the movie’s thespian highlights. The resolution rings false, and Bonnie and Rochelle’s motivations fall badly out of focus as the conflict between Nancy and Sarah escalates. Chris makes very little sense as a character, and it’s never believable that Sarah would feel any attraction to him. And although this obviously isn’t a fair criticism, I could never hear any of the characters call Manon by name without mentally substituting “Manos.” Nevertheless, The Craft is serviceable enough when operating as a teen angst melodrama with a fantasy overlay. Unfortunately it abandons that mode almost completely a bit beyond the halfway mark, counterproductively emphasizing the power that Nancy can bring to bear against her enemies over her reasons for wanting to do so. By the third act, we’re left with nothing but a shitty PG-13 horror movie— albeit one which got slapped with an R anyway, because the mere suggestion of minors practicing witchcraft was enough to give Fundamentalist Christians the vapors, to say nothing of such overt treatment of paganism as a valid and potentially beneficial spiritual perspective as we see here.

On the other hand, although The Craft may be no better than I recalled, it is a great deal more interesting. The aforementioned guardedly favorable attitude toward paganism is a major reason why, but because that ties directly into what I was talking about at the beginning of the review, I’m going to postpone discussing it specifically for a bit. What first jumped out at me upon revisiting The Craft was the similarity of its premise to those of a whole phalanx of roughly contemporary movies and television shows that I had not previously perceived as being closely related. Think about entertainment aimed at the youth market of the 90’s, and consider how frequently one sees stories about groups of adolescent or post-adolescent weirdos— self-identified weirdos, more often than not— banding together in opposition to someone or something that can be taken as representative of “normal” society. Obviously that sort of thing existed before the 90’s as well, but there’s an important difference in how the subject was handled. In prior eras, the “misfits make good” plot template was almost exclusively the domain of comedies, where the upending of social order and conventional values implicit in that trope could be rendered non-threatening by deliberate absurdity. Animal House, Rock ’n’ Roll High School, Meatballs, Stripes, the Police Academy movies, The Belles of St. Trininan’s and its sequels— they all portray the rebellion and ultimate triumph of the outcast as a harmless underdog fantasy for the audience to laugh along with, and a fair proportion of them subtextually affirm the values that their protagonists profess to reject by letting the misfit heroes accomplish some goal that straight society considers laudable. That’s not necessarily the case with 90’s rebel youth movies, though. In the 90’s, the revenge of the ostracized took on a seriousness that it hadn’t previously had save in a few films like If…, which were consciously intended as indictments of institutional malfeasance. Not only were films of this new breed willing to face squarely the threat their protagonists posed to the status quo, but they frequently went the extra step of making that threat attractive. It was one thing to root for the boys of Lambda Lambda Lambda in Revenge of the Nerds, but something else again to cheer on Veronica Sawyer and J.D. in Heathers. The latter film, although released at the tail end of the 80’s, looks to me like ground zero for the 90’s approach to teenage rebellion, while the TV version of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” represents, I think, its final ascension to more or less mainstream respectability; not coincidentally, the outsider protagonists of those two works also stand as opposite poles of a continuum between antihero and superhero, along which the portrayal of insiders correspondingly softens from inherent and inoperable corruption to mere misguided cluelessness. And in between those endpoints, we find such transitional specimens as Pump Up the Volume, the Buffy the Vampire Slayer movie, Hackers— and of course The Craft.

One has to ask what happened in the 90’s to bring about this change. My own tentative hypothesis is that it has something to do with the end of the Cold War, and with the rise of the stock market-based casino economy. The collapse of the Eastern Bloc between 1989 and 1991 left the alliance systems designed to oppose it with no clear mission, and the curb-stomping Iraq received in the first Persian Gulf War at the same time demonstrated that not even the world’s third-largest land army was a match for NATO in a stand-up fight. For the first time since before the Napoleonic Wars, the governments and inhabitants of Western nations could afford to go about their business without sparing a thought for international balances of military power. Meanwhile, the shift from an economy based on making stuff and selling it to one based on trading IOUs back and forth created the illusion of such vast wealth that once the recession at the very beginning of the decade was sorted out, fifteen years went by before anyone seemed to worry much about the fact that none of that money actually existed. With the pressing matters of security and prosperity assumed to be no longer at issue, there was plenty of mental energy and surplus outrage available to be channeled into questions of cultural values. It should not be surprising, then, that Westerners in general and Americans in particular spent the 1990’s arguing most heatedly over subjects like the legality of abortion, women and gays serving in the military, and “speech codes” purporting to hold college students accountable for saying hurtful and offensive things on campus. Furthermore, a lot of effort went into inciting young people to take sides in those debates (witness MTV’s “Rock the Vote” campaign, for example), and teenagers being what they are, it was perhaps inevitable that they would do their side-taking along tribal lines. It was therefore easy, if you were eighteen years old in 1992, to see the social strife between weirdos and popular kids— or between teens and parents, or students and school authorities— as a microcosm of the culture wars grownups were waging at the same time. Whenever a zeitgeist exists to be tapped into, it’s a safe bet that the entertainment industries will try to do so, and it may be that in this particular decade, the perceived congruence between young people’s struggles and their elders’ gave the filmmakers, the TV writers, the comic book artists, and so forth an unusual incentive to get it closer to right. And so in The Craft, Nancy is not quite the shrill goth caricature we might normally anticipate. She and her fellow witches are shown to have legitimate grievances which not only help to justify their behavior, but also call into question the validity of a social order which has no place for them. And although Nancy, Bonnie, and Rochelle are punished to varying degrees for their misdeeds, it is made very explicit that turning to magic and paganism per se was not among those; witchcraft in The Craft is a tool that Nancy misuses, not something inherently evil or corrupting. So again, The Craft is not a good movie, but it is an interesting one, revealing more about its era than anyone involved in making it could possibly have known or intended.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact