Manos: The Hands of Fate (1966) -****

Manos: The Hands of Fate (1966) -****

I no longer remember where or when I first encountered the phrase “outsider art,” but given my tastes, it quickly became a very useful addition to my conceptual toolkit. Also known as intuitive art, visionary art, naïve art, and an inevitable constellation of borrowed French terminology, outsider art is exactly what it sounds like: art created by people operating in deep isolation from the mainstream of their chosen field. Outsider artists have little or no formal training, receive little or no support from the culture industries, and enjoy little or no prospect of achieving financial prosperity or critical approbation through their work (unless they’re dead, of course— then the critics start fawning and the sales to galleries and well-heeled private collectors commence). They may use improvised media, strange techniques of their own devising, or subject matter so particular to their own psyches as to be nearly (or indeed completely) incomprehensible to anyone else. Not infrequently, outsider artists are markedly eccentric if not downright crazy. They might be painters, drafters, poets, sculptors, musicians, playwrights, photographers, collage artists, or handicraft specialists. In fact, about the one thing you’d naturally expect an outsider artist could not be is a commercial filmmaker. After all, a feature film intended for exhibition to a paying public is an inescapably collaborative undertaking, whereas outsider art just as inescapably depends upon individual weirdos pouring out the contents of their peculiar brains, uninhibited by social norms, consumer expectations, or even considerations of talent. Making a movie is also more expensive by orders of magnitude than writing a novel, recording a song, or building an eight-foot scale model of the Lusitania out of toothpicks. Unless you’re independently wealthy, you’re going to need investors; investors are going to want their money back at some point; and the cinematic equivalent of a Wesley Willis album is apt to sell too few tickets even to recoup its lab costs, let alone pay anybody back. That being the case, it is perhaps apt that one of the rare examples of true outsider art among commercial motion pictures was made by a guy who literally sold bullshit for a living.

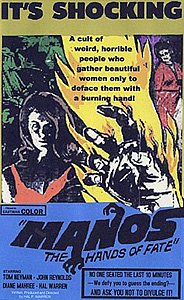

Well, technically I suppose it’s possible that Hal Warren’s El Paso fertilizer business specialized in the variety based on synthetic nitrogenic chemicals, but given the long-established prominence of the cattle industry in Texas, I’m thinking manure was a big part of the trade. In 1966, when a gig as an extra and location scout for the TV show “Route 66” brought him into contact with Stirling Silliphant (a very prolific screenwriter who was at that time a regular contributor to the program), Warren’s only entertainment industry experience was a bit of community theater acting, yet he somehow got it into his head that any fool could do what Silliphant was doing— and told him as much. Moreover, Warren bet Silliphant that he could make a movie himself, right there in El Paso, serving as writer, director, producer, and star, and get it released to theaters (or at least the local drive-in). This, as anyone with actual filmmaking experience would recognize at once, was a nearly insane boast, and it is only to be expected that the resulting film— Manos: The Hands of Fate— is a completely insane movie, bearing virtually no resemblance to anything normally seen on theater screens. It is a testament to the ravenous content appetite of independent exhibitors in the mid-1960’s that it managed to secure any bookings at all— especially after word of its ignominious El Paso premiere (from which many if not most of the attending cast-members stealthily fled in humiliation) got out.

Mike (Warren himself), his wife Maggie (Diane Mahree), and their little daughter Debbie (Jackey Neyman, one of the very few members of this cast with any other before-the-camera credits to their names— but since her one other movie was Curse of Bigfoot, maybe that’s nothing to be very proud of) are on a road-trip vacation, passing at the moment through the hinterland of El Paso. They’ve also brought along Debbie’s poodle, Pepe, but that won’t matter for some considerable while. It’s unclear whether the Valley Lodge is their actual destination, or merely a convenient stopping point for this stage of the journey, but when they see the sign identifying an ill-maintained turnoff as the route leading there, they leave Highway 10 in quest of the place. Along the way, they pass by a young couple (Bernie Rosenblum and Joyce Molleur, who are not nearly as young as they’re probably supposed to be) making out in a sports car parked beside the road. These two are here to do just one thing— to remark that nobody ever drives out this way anymore, because there hasn’t been anyplace to go on this road for years— yet they will repeatedly resurface throughout the film, as will the two even more functionless highway patrolmen (George Cavender and [get this] William Bryan Jennings) who roust them from one trysting spot after another.

Anyway, the turnoff goes on and on, becoming more and more raggedy with each passing mile, and true to the Makeout Couple’s word, there doesn’t seem to be so much as a farmhouse fronting onto it, let alone the Valley Lodge. Maggie begins to fret (she’s a veritable fretting machine, as we’ll soon see), and although Mike grumpily dismisses her worries at first, eventually even he is forced to conclude that they’re going the wrong way. A funny thing happens after they turn around to retrace their route to the highway, however. Even though Mike is certain that they’ve done nothing but to reverse their previous course, they nevertheless come upon a dilapidated but clearly occupied house where they could scarcely have failed to notice one had they driven by it before. It doesn’t seem likely that this is the Valley Lodge (at the very least, one would certainly hope it wasn’t), but maybe whoever lives there can provide some decent directions.

Or not… The man who greets Mike and his family at the front door is a twitchy, gnomish, gimpy-legged, creaky-voiced weirdo who introduces himself as Torgo (John Reynolds), and cryptically clarifies that he takes care of the place “while the Master is away.” Torgo avers not only that this is not the Valley Lodge, but indeed that no such place exists anywhere nearby. Then, making once more with the cryptic, he answers Mike’s request for directions back to Highway 10 by saying that there is no way back. The sun is noticeably on its way down by this point, so Mike counters by asking if he, Maggie, and Debbie can spend the night at Casa Torgo. This earns the most baffling reply yet. Torgo starts off by warbling that the Master wouldn’t approve of him letting unexpected guests stay overnight, yet changes his tune in mid-utterance for no readily apparent reason. Then he reverses himself again. And then he does so once more, this time on the grounds that the Master “likes” Maggie. Torgo does not volunteer how this unseen Master could be in a position to like someone whom he has yet to meet, nor does Mike or Maggie think to ask. Hell, it isn’t even clear at the moment who the Master is. In any case, Torgo hobbles over to the car to get the visitors’ luggage— because obviously you’d make the guy with deformed legs, who needs to lean on an iron staff to walk at even the most halting and feeble pace, carry all your shit. (And by the way, it isn’t often that an actor turns walking into a big enough production to merit its own musical cue, but I think you’ll all agree once you see him in action that Reynolds more than earned his unforgettable “Torgo Walks” theme.)

Stepping over the threshold into the living room does at least furnish something resembling the answers to our questions about the Master. For the most part, Torgo’s home presents the sort of rundown but ordinary aspect that one would expect from a house in the West Texas countryside with no one to maintain it except a guy who has difficulty walking a straight line. Two items are strikingly unusual, however: the fireplace, which has been converted into a very pagan-looking shrine, and the painting hung up on the adjacent wall, which depicts a mustachioed man in a black-and-red robe, holding the leash of a very large and obviously vicious dog. Mike correctly surmises that the man in the portrait is the Master, which provokes Torgo to another outburst of barely coherent rambling. This time, the caretaker says that the Master “is no longer with us,” but that “he sees us everywhere we go.” Maggie reasonably assumes that Torgo means he’s dead, but apparently not. Or something. Whatever the hell “not dead like you know it” means, in any case.

Even if Mike, Maggie, and Debbie had nothing more in mind for their vacation than watching their toenails grow at the Valley Lodge, I guarantee you that would have been preferable to what happens over the course of the night at Torgo’s house. To start with, there’s some kind of large animal prowling around outside, and its persistent howling terrifies Maggie. Mike goes out in the hope of scaring the creature away with the pistol he keeps in the car’s glove compartment, but all that accomplishes is getting Pepe killed. The dog runs out the door along with Mike, and unlike his owner, Pepe finds the mysterious howling beast; Mike finds only Pepe’s mutilated carcass. For once, Maggie’s trepidation is clearly warranted, and Mike summons Torgo to return the luggage to the car. The engine won’t turn over, though, and while Mike wrestles fruitlessly with that problem, the caretaker wobbles back inside to hit on Maggie in what I promise you is one of the most genuinely uncomfortable scenes you’ll ever see in a movie. While he’s at it, fondling Maggie’s hair and twitching incessantly, Torgo blathers about how the Master wants her for his wife, but how he can’t have her because Torgo means to get her instead. Mike comes back inside with the bad news about the car just after Maggie has finished setting Torgo straight, and then it’s on to the next bizarre crisis— Debbie has run off somewhere.

The girl returns soon enough, but she freaks her parents out even more by bringing with her an enormous dog which she calls “Fluffy.” Two things about this animal are immediately apparent. First, Fluffy has to be the thing that killed Pepe earlier, and second, he’s a dead ringer for the Hellhound in the painting of the Master. After Mike somehow manages to chase the beast away, Debbie explains that she found Fluffy in “a big place,” and that there were “all kinds of people” there. Thinking her discovery might translate into a way to put this increasingly unpleasant evening behind them, Mike instructs Debbie to lead him and Maggie back the way she came. What they find is a sort of tomb, in which the man from the painting (Tom Neyman— Jackey’s dad in real life) and six women (Stephanie Nielson, Sherry Proctor, Robin Reed, Jay Hall, Bettie Burns, and Lelanie Hansard) lie uncannily preserved despite being out in the open on stone slabs or propped against the pillars supporting the ceiling, arranged around a more developed version of the altar converted from Torgo’s fireplace. Obviously this is no way out of anything, and the family immediately high-tail it back to the dubious safety of the house. If they’d stuck around just a little longer, they might have witnessed the Master and his wives rising from their death-like sleep…

Now Manos: The Hands of Fate has been an extremely odd movie from the get-go, but only after the resuscitation of the Master and his harem does it become unmistakably apparent that Hal Warren cannot possibly have written anything more involved than a shopping list since the day he left high school. Certain plot developments do follow more or less logically from what we’ve seen thus far. Torgo, for example, makes the expected play to eliminate Mike with the aim of claiming Maggie for himself, and in the process sets up a later conflict between him and the Master. The Master and his harem also form evil designs on Mike and his family, seeking to enfold them into what might be very generously described as their web of corruption. But if you’re waiting for some kind of motivation for the bad guys’ behavior to emerge, or for anything more than the vaguest hints about the nature of the Master, his minions, or the demonic deity they worship (the titular Manos), then you’re going to be waiting in vain. What I’d describe as the third act if Manos: The Hands of Fate had any discernable story structure is a mind-paralyzing tangle of non-sequiturs, beginning when it cuts immediately from the Master intoning the invocation to Manos that will awaken his wives to the six women sitting around in a big circle, chattering away in an indecipherable Babel of bickering. Eventually, it comes out that what the ladies are arguing over is the fate of Mike, Maggie, and Debbie; between the two extreme positions (one wife demanding that all of the interlopers be exterminated, and another opining that she’s had her fill of killing for one eternity), the main bone of contention concerns whether to kill Debbie or to keep her around until she reaches the age at which she could become the eighth Mrs. Master (the number-seven slot being presumptively assigned to her mother). The debate eventually explodes into a free-for-all catfight that consumes nearly the whole final third of the film! The friction between Torgo and the Master doesn’t play out at all sensibly, either. Oh, it’s reasonable enough that the Master would find Torgo’s rebellion over the final disposition of Maggie intolerable, and that he, as an evil mastermind, would impose the death penalty for this perceived disloyalty. What isn’t reasonable is that Torgo would have to be killed three times— once by the Master’s mind powers, once by the wives (who apparently massage him to death), and once by the intervention of Manos himself— or that this triple killing would nevertheless prove markedly non-fatal. And as for the intrusion and re-intrusion of the Makeout Couple and their nemeses on the highway patrol, they become comprehensible only when you understand that Joyce Molleur had originally been cast as one of the Master’s wives, but broke her foot falling from her perch on one of the pillars in the tomb. Warren, having hired her, was determined to have her in the movie, so he wrote her a new part, and hauled jack-of-eighteen-trades crewman Bernie Rosenblum out in front of the camera for a nineteenth job playing her boyfriend.

Indeed, several of Manos: The Hands of Fate’s more puzzling characteristics become explicable in light of things going awry behind the scenes. You will notice, for instance, that characters who profess to be looking for something or someone at night invariably display a marked reluctance to do any credible searching. This is because the lighting for the outdoor scenes was wholly inadequate; those five-pace search radii are approximately congruent with how far the camera could see! Camera limitations similarly explain why the driving montage early on dissolves at roughly half-minute intervals between virtually identical bits of undistinguished West Texas countryside. The camera Warren acquired for the shoot used a clockwork motor rather than electric power from a battery pack or AC adaptor. It had to be wound up before each shot, and its mainspring could absorb only enough energy to power the other internal machinery for 32 seconds at a time. Nor did the camera allow for synchronized sound recording, although that technical shortcoming goes only so far toward absolving the wretchedness of the film’s post-looped dialogue. After all, with one conspicuous exception, there’s no obvious reason why Warren couldn’t have brought the original cast with him to the recording studio during post-production, rather than dubbing nearly all the male voices himself. The comically unflattering bullet bras and granny panties worn by the Master’s wives, meanwhile, may be attributed to a different sort of unforeseen complication. Originally, the women were to have been nude beneath their diaphanous robes, but the owner of Mannequin Manor (the small El Paso modeling agency from which the “actresses” had been hired) would tolerate no such heathen immodesty from any of her girls.

And then there’s Torgo. Depending on my mood, I find him either the most marvelously god-awful feature of this marvelously god-awful film, or the one thing about it that sort of accidentally works. And make no mistake— to the extent that Torgo works, it is very much an accident. John Reynolds was an extremely troubled young man, so much so, in fact, that he killed himself very shortly after the filming of Manos: The Hands of Fate was completed. He was a habitual drug user, and he reportedly spent pretty much the entire period of principal photography high on LSD. He never could figure out how the contraptions Tom Neyman designed to give Torgo his remarkable leg deformity were supposed to work, and wearing them wrong left him nearly incapable of walking while in costume. (Incidentally, according to Bernie Rosenblum, Torgo’s legs look like that because he was supposed to be a satyr. I can’t make up my mind whether never, ever mentioning that in the film was a commendable display of trust in the viewer’s intelligence, or merely one more example of how incompletely Warren thought Manos through.) The voice on the soundtrack belongs to somebody else altogether (it sounds like Warren’s, but the creaking makes it difficult to be sure), perhaps because Reynolds was already dead by the time the film was ready for post-looping; in any event, he certainly didn’t live to see the premiere. All these things add up to a performance so utterly outside the parameters of normality that it occasionally becomes a source of real discomfiture. Torgo is like an awkward silence in human (or I guess satyr) form, and to the extent that anything ever works in this movie, it works because of him.

The rest of the movie, though… Well, let me describe a single shot, in detail, and let it stand for Manos: The Hands of Fate as a whole— because it truly is representative. Toward the end of the film, the Master takes matters into his own hands and shows up at the house with the Hellhound at his side. Mike, understandably, is the first to face him, and it’s from his point of view that we see the Master’s entrance. He storms in looking very cross and moustachey, but a quick downward pan of the camera establishes that Mike’s attention is justly focused more on the dog instead. We get a zoom in on the Hellhound’s face, and then… the dog sits there, looking at the cinematographer. The camera stares. The Hellhound sits. The camera stares. The Hellhound sits. The camera stares. At long last, the dog barks happily, and Hal Warren evidently decides that’s good enough, finally putting the shot out of its misery. Retakes? Bah— film stock costs money, you know. Besides, you can always fix a thing like that in editing, right? Rosenblum recalls “We’ll fix it in editing” or “We’ll fix it in the lab” being Warren’s stock answer to everything that went unanswerably wrong on the set, which is rather puzzling in retrospect; if any effort was made to fix anything in either the editing room or the development lab, there’s certainly no evidence of it in the completed film! As Jim Morton says of Manos in Re/Search #10: Incredibly Strange Films, it’s hard to believe that Warren left even a single frame on the cutting room floor. One of the less-remarked virtues of outsider art is that exposure to it can deepen one’s appreciation for and understanding of art of the ordinary sort, for an untrained, unsophisticated, unprepared creator like Warren will frequently violate conventions and break rules that you didn’t even know existed, for the simple reason that they didn’t know those rules and conventions existed either. It’s nearly impossible to defend Manos: The Hands of Fate as a good movie, or even an entertaining one— not entertaining like you know it— but it undeniably represents as singular a vision as any commercial motion picture ever made.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact