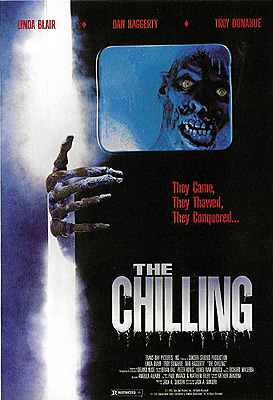

The Chilling (1989) **

The Chilling (1989) **

In 1954, researchers at the University of Iowa impregnated three women by artificially inseminating them with sperm that had been carefully frozen and thawed. It was the first time a living human cell had been treated thusly without being destroyed in the process. Eight years later, Robert Ettinger, who had been fascinated with the concept of cryogenic preservation ever since a childhood reading of Neil R. Jonesís sci-fi story, ďThe Jameson Satellite,Ē wrote a book of his own called The Prospect of Immortality, in which he argued that it was only a matter of time before advances in medical science made it possible to freeze and restore entire human bodies. Once frozen, Ettinger enthused, a person could be preserved indefinitelyó not merely for the purposes of interstellar travel, but to cheat death itself by waiting out however many centuries it might take to discover cures for this or that illness or injury. Indeed, as the title of his book implied, Ettinger saw no reason why cryogenic preservationó or ďcryonics,Ē as he called itó shouldnít allow us to outwait a cure for the aging process itself, so that no one from then on need ever die at all. We could all get frozen on the gangway to Charonís wharf, then thawed out to enjoy an unending second life whenever the necessary technology became available.

That might sound like utter crankery (not least because it is), but enough people found it convincing that by 1964, organizations of immortality enthusiasts started cropping up, with names like Cooperís Life-Extension Society and the Cryonics Society of Michigan. (The latter was Ettingerís own outfit, known today as the Immortalist Society.) The first person to take the whole thing seriously enough to have himself actually frozen upon his death was a University of California psychology professor called James Bedford, who succumbed to metastasized renal cancer on January 12th, 1967. Bedford remains packed into his high-tech cooler to this day, although several different cryonics firms have had custody of him over the years. I havenít been able to pin down exactly when cryonics became a business, rather than just an oddball area of research, but it happened no later than 1969. Should you happen to die with a few hundred grand burning a hole in your pocket, a number of different companies can pump you full of mysterious chemicals and lock you in a freezer. Some of them might even be able to keep you from rotting indefinitely the way they all say they can, but none of them as yet can make you any less dead.

In any case, for reasons I donít quite understand, cryonics enjoyed an anomalous moment of pop-culture visibility in the late 80ís and early 90ís. The Chilling was among the lesser products of that extremely minor fad. It uses cryonics as the jumping-off point for a zombie story, but stubbornly refuses to engage with any aspect of the premise that might make it interesting to do so. For all the impact that the process-specific details ever have on anything, it might as well be toxic waste, an experimental military defoliant, or radiation from a wayward Venus probe bringing The Chillingís dead to life.

Ilene Davenport (Suzanna Camp), longtime wife of fat-cat Kansas City businessman Joseph Davenport (Jack De Rieux), has just died. You donít have to take dead for an answer, though, if you have Davenport moneyó at least not if you believe Dr. Miller (Troy Donahue, from The Pamela Principle and Deadly Prey), the head of the ďlife-extension companyĒ Universal Cryonics. With UCís secret super-preservative and a refrigeration plant capable of sustaining temperatures of –320 degrees Fahrenheit, the dearly departed can be kept fresh as a daisy for however long it takes to develop a retroactive cure for what ailed them. Itís a scam, of course, but that doesnít mean Dr. Miller is a charlatan. No, his process really can do everything he claims. Itís just that instead of retaining his customersí corpses in anticipation of a resurrection that will never come, he harvests as many of their perfectly-preserved organs as are still usable for sale on the international black market for transplants. Some of Millerís employees, like cryogenic engineer Jerry Kardell (Steve Gluck), know whatís really going on at Universal Cryonics. Others, like office administrator Mary Hampton (Linda Blair, of Witchery and Grotesque), do not.

Six months later, on Halloween morning, Davenportís dirtbag son, Joe Jr. (Deeply Disturbedís Ron Vincent), gets himself and four accomplices killed while robbing a bank. Joe Sr. commits his body to Dr. Millerís care, too, but the bossís conduct during the intake meeting provides Mary with her first clue that her workplace isnít entirely on the up-and-up. She has no chance to share her newly-formed misgivings with Davenport, though, until quitting time, when the unreliability of her own car creates an opportunity to hitch a ride home in Josephís limo.

Meanwhile, night-shift security guards Vince Marlow (Dan Haggerty, from Bury Me an Angel and Hex) and Mark Evans (Michael Jacobs, of Love Me Deadly and The Dead Pit) are bracing for a fierce electrical storm thatís supposed to hit Kansas City later that night. After all, power outages are serious business for a cryonics firm. Sure enough, lightning knocks down the power lines to the Universal Cryonics campus just as the storm is reaching the peak of its intensity, but thatís only the start of the trouble. Universal Cryonics naturally has its own onsite emergency backup generator, but that system fails, too, after just a few minutesí operation. Thinking quickly, Marlow remembers the weather report saying that the storm was riding into town on a freak cold snap. That should make it markedly cooler outside the lab building than insideó not –320 degrees, obviously, but chilly enough that the frozen stiffs will be in less danger of thawing out before power is restored if Vince and Mark fire up the forklift, and shift all the cryogenic pods to the loading dock out back. Alas, that makes the freezers lightning-attractors in their own right. Also, it just so happens that one of the incidental properties of Millerís preservative fluid is its extreme electrical conductivity. Each lightning strike on a freezer pod jolts the corpse within into unlife as a zombie, their dispositions falling somewhere between the George Romero model and the Sam Raimi.

At first, the zombies are strictly the security guardsí problem. But because Vince had already made a round of phone calls alerting various responsible parties to the dual power failure, he and Mark will soon be far from alone against the living dead. The power company sends a pair of technicians (Matthew Riley and Robert Clark) to help get the emergency generator back online. Mary, ever the mother hen, has Davenport turn right around and return her to work when she comes home to a ringing phone and a harried guard on the other end of the line. Dr. Miller and Jerry Kardell turn up, too, under circumstances suggesting that they might never have left the office in the first place. And Maryís jealous, drunken lout of a boyfriend, Steve (John Flanagan), goes in pursuit of her, determined to have it out with Davenport; no rich asshole gives his girl a ride home, damnit! Inevitably, most of these folks are going to wind up zombie chow before the night is through.

Did you notice the big damn deal that The Chilling makes of including Joseph Davenportís loved ones among the corpses in Dr. Millerís refrigerators? And did you notice how far out of the way writers Guy Messenger and Jack A. Sunseri (the latter of whom was also The Chillingís co-director) go to place Davenport on the scene of the zombie uprising? So obviously that must mean Davenport will have to face undead versions of his wife and son, right? And on terms closer to Ash battling Linda and Cheryl in The Evil Dead than to Johnnyís ironic membership in the horde that kills Barbara in Night of the Living Dead? I mean, wouldnít such a fraught confrontation have to be the entire fucking point of setting a zombie movie at a commercial cryonics lab? Nope. Indeed, I canít even confirm that Ilene is among the risen corpses at all, and although Joe Jr. definitely is, his faceoff with his dad is a perfunctory affair, made still more annoyingly forgettable by its failure to take any account of what a nasty piece of work the kid had been even when he was alive. Thatís the kind of thing I meant when I accused The Chilling of refusing to engage with its own premise.

There are plenty of other examples, too. The zombies donít seem to have it in for Miller or Kardell any worse than they do for, say, the guys from the power plant, despite all the movieís emphasis on how Universal Cyronics fucks over its customers, both the living and the dead. Nor does Joe Jr. show any special animosity toward the father who handed him over to Millerís clandestine organ farm. And no distinctions are drawn among the zombies based on how long theyíve been in the companyís custody, having their body parts sold off to crooked millionaires with cancerous lungs and fatty livers. Itís impossible to overstate what a missed opportunity that is, too. Seriously, imagine how disturbing it would be if a significant cohort of the zombies were visibly incomplete somehow. Imagine how disturbing it would be if instead of eating the flesh of their victims, the undead were trying to replace the parts that had been stolen from them. The filmmakersí obliviousness to such possibilities makes it doubly disappointing that they delivered instead as rote and weary a gut-muncher as any to emerge from the micro-budget filmmaking scene in the decade to come, with considerably less excuse.

The Chilling is also objectionable on account of sheer narrative inelegance. Why send Mary home, only to call her back to Universal Cryonics after the zombies have escaped from their freezer pods? Why include two largely duplicative creeps in the form of Joe Jr. and Steve, especially if the formerís sociopathy isnít going to matter after he returns from the dead? Why waste time on Kardellís trashy affair with his lab assistant (Jori Goodman), and then not even keep her around to inflate the body count? And who gives a shit that this is all happening on Halloween, since the closest the date ever comes to mattering is when Messenger and Sunseri throw us all right out of the film by having Steve encounter a trio of trick-or-treatersó at midnight, in the midst of a ferocious thunderstormó on the way out the door to chase after Mary and Joseph? (Hang onó Mary and Joseph?! Really?!?!) No two pieces of this story fit together without an ugly glob of spackle or a row of crooked staples drawing attention to themselves.

Nevertheless, thereís just enough workmanlike competency on the technical side of the production to render The Chilling tolerable for most of its modest length, together with a solid core of redeeming thespian professionalism thanks to Linda Blair, Troy Donahue, and Dan Haggerty. The cryogenic lab and the zombies inhabiting it all look good, or at least good enough. So do the lighting and the cinematography, in a way that we used to be able to take for granted even in much cheaper films than this one, back before everything had to be shot with at least one eye toward facilitating digital post-production tweaks. Blair, Donohue, and Haggerty are all B- and C-listers, to be sure, but they know what it takes to leave an impression on the audience, and their presence here goes a long way toward making up for the dinner-theater nobodies who comprise the rest of the cast. So although itís very difficult to like The Chilling, it isnít really worth hating, either.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact