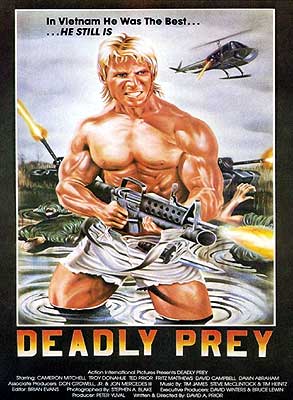

Deadly Prey (1987) -***Ĺ

Deadly Prey (1987) -***Ĺ

Itís been a big couple of months for me discovering unsung regional filmmakers of the direct-to-video era. Last time it was Bret McCormick, and now itís Alabamaís David A. Prior. Prior is a much more significant figure than McCormick, however, for he appears to be the original direct-to-video auteur. His debut feature, the surreal supernatural slasher Sledge Hammer, is the current record-holder for earliest known feature made from the outset for release on home video (indeed, it holds the further distinction of being actually shot on videotape). Horror was not Priorís real area of interest, though, if we may judge from his subsequent career. Rather, Prior aspired to make action movies of a sort that sound impossible given the resources he was able to commandó the kind with mercenary armies, terrorist cells, military-grade firearms by the truckload, and lots and lots of explosions. Sometimes the results were dreary and stultifying (as in Priorís tragically mishandled boobs-and-bullets opus, The Mankillers, in which an ad-hoc commando team of female convicts take on a vicious cartel of international vice traders, and apparently bore them to death), but damned if he didnít realize his ambitions. Heís still at it, too, although heís slowed down considerably since the turn of the century. Obviously that genre focus places most of Priorís work outside my purview here, but Deadly Prey manages to sneak in through the back door. This may be a Weightlifter with a Machine Gun movie first and foremost, but itís also a riff on ďThe Hounds of Zaroff,Ē and you know how I am about those.

The Zaroff analogue here is Colonel John Hogan (David Campbell, from Evil Altar and Speak of the Devil), a former special forces commander who resigned from the US Army in disgrace. He evidently doesnít like to talk about the exact circumstances, but I gather it had something to do with the methods whereby he trained and maintained discipline among his men. Whatever really happened, Hogan is now pursuing the usual second career for retired action-movie Green Berets, assembling a mercenary army of dubious legality. We never will learn what the aim is, but the funding is coming from someone named Michaelson (Troy Donahue, of Monster on the Campus and Hard Rock Nightmare), who could equally well be a corrupt businessman, a corrupt politician, or both. (Iím guessing heís at least a state senator if he holds elected office.) And as Iím sure youíve already surmised, Hoganís methods have grown even more unorthodox since he was drummed out of the service. His recruits practice guerilla warfare by abducting drifters and hunting them through the wilderness around their base camp 70-some miles southeast of Los Angeles. These hunts are led by Hoganís right-hand man, Lieutenant Thornton (Killer Workoutís Fritz Matthews), who is also charged with killing any trainee whose performance falls below a fairly unforgiving minimum standard.

Michaelson is unhappy with the pace of Hoganís preparations, however, and the resulting hustle to meet the clientís deadline becomes the whole operationís undoing. A nearer starting date demands an accelerated training schedule, which in turn requires more frequent ďfoxhunts.Ē More foxhunts means more foxes, and that means Hogan can no longer afford to limit himself to people whom nobody would miss. Thornton is driven to the crude expedient of snatching men straight off the street in broad daylightó and in suburban neighborhoods, no less, where the odds of the victims leaving a family to come looking for them approach one to one. But Mike Danton (Ted Prior, the directorís brother, to whom he turned for all his strapping, blond mullet-god needs) doesnít just have a wife (Suzanne Tara) whoíll notice at once when he doesnít come home from taking out the trash one morning. Mikeís father-in-law (Cameron Mitchell, from Knives of the Avenger and The Offspring) is a retired cop of the Dirty Harry persuasion, which obviously bodes ill for anyone who might try to harm any member of the family. But beyond all that, Mike and Hogan have already met. When Hogan was still in the army, pushing the limits of military ethics to create the perfect special forces killing machine, Danton was his star pupil.

From the moment Thornton escorts Danton to the edge of the mercenary camp and orders him to run, Deadly Prey consists almost entirely of Mike slaughtering the shit out of Hoganís minions. The carnage is almost literally non-stop. That isnít to say, though, that thereís no story here. As Iíve already implied, thereís Jaimy Dantonís attempt to find her husband by turning her father loose on the case. Thereís also a plot thread in which one of Hoganís newest recruits (William Zipp, of Future Force) turns out to have fought alongside Danton in Vietnam (nevermind that both of these guys would have been about fourteen years old when the last chopper lifted off from Saigon), and switches sides to aid Mike in his struggle for survival. But most interestingly within the context of this extremely narrow and rigidly defined subgenre, Hoganís objective quickly shifts from killing Danton to drafting him into the mercenary army. The colonel courts him at first with appeals to loyalty and comradeship, invoking their common experiences in ĎNam. When that doesnít work, he unleashes his heavily hairsprayed femme fatale sidekick (Dawn Abraham, from Prisoners of the Lost Universe) to play on a different side of Mikeís manhood. And when all else fails, Hogan turns to extortion. Jaimyís rescue mission starts looking less like a lifeline for her husband, and more like her playing right into Hoganís hands.

Nothing Iíve said so far remotely suggests what itís really like to watch Deadly Prey, however. To get that, you have to understand the utter amateurismó in both senses of the wordó that David Prior brought to the project. Priorís script reveals no concept of character motivation, no conscious awareness of story structure, no ear for dialogue. What it does show is a childlike enthusiasm for getting to and staying at the Good Part, together with an impressive if undisciplined inventiveness in devising set pieces. And above all, Prior displays the sensibility of a true fan seeking to make the kind of movie he most wants to watch. Simply put, Deadly Prey is a film in which things happen because theyíre totally awesome, and in which no other reason for them to happen is necessary. The best example is the final clash between Danton and Thornton. I wonít tell you what transpires, because itís the kind of thing you really should see cold, but I will tell you this: the young Peter Jackson or one of the more talented filmmakers within the Troma stable might have come up with something similar as a sick joke, but Prior appears to have done it in all sincerity.

Thereís also an interesting tonal effect in the third act which Prior seems to have arrived at naively, but which is no less potent for that. For the first two thirds of its running time, Deadly Prey is about as 80ís an action movie as itís even theoretically possible to be. Mike Danton is quite simply invincible, and at no point do the bad guys credibly stand a chance against him. Meanwhile, there isnít the slightest hint of ambivalence about the morality of answering extreme violence with even more extreme violence, and not even Jaimyís ex-cop father makes any attempt to deal with the situation through the approved channels. Until about the hour mark, then, Deadly Prey is functionally equivalent to Death Wish 3 and Rambo: First Blood, Part II in one. But as the endgame begins, the film goes all 70ís on us, with a bummer denouement full of madness and tragedy, and an almost arty open ending that resolves nothing, yet leaves no question about whatís going to happen on the other side of the closing credits. In that sense, Deadly Prey is almost a mirror image of the original First Blood, which starts off like a somber straggler from the previous decadeís New Hollywood movement, then goes 80ís Explosion Movie berserk after Rambo decides heís not done with that shitty little hick town after all.

As a director, meanwhile, Prior might best be described as sort of crudely competent, at least on the basis of Deadly Prey. Nothing really stands out as a shining example of the artó or even the craftó of cinema, but the action scenes are effectively blocked and coherently orchestrated, which is more than you can count on at this stratum of the industry. That isnít to say that the fights are especially credible (the one where Danton takes on a mercenary-crewed M-47 main battle tank is ludicrous even by prevailing genre standards), but thereís nothing like a modern shoot-íem-up picture to make you nostalgic for the days when action directors knew the importance of keeping the camera still once in a fucking while. And to return to that M-47, I have to applaud Priorís ability to marshal production-value resources. Deadly Prey looks like a much bigger movie than it is, and it takes a practiced eye to notice where the corners were cut. Most notably, Prior makes good use of the tank yard at the Military Heritage Museum to enhance the appearance of Hoganís encampment. Reasonably adept tank-spotters will quickly notice something fishy about the motley collection of equipment at the colonelís base, but all that heavy hardware undeniably serves to make the mercenary army look more formidable than the corporate team-building getaway at the local paintball range which they would resemble otherwise.

Iím even willing to give a little bit of credit to the cast, which apart from veterans Cameron Mitchell and Troy Donohue is mostly semiprofessional at best. These people clearly understand the concept of acting, even if the actual practice rather eludes them; that too is more than you can safely assume in productions of this kind. Ted Prior is fairly hopeless at first, when heís trying to portray Dantonís normal life, but he improves markedly once heís running around shirtless and barefoot in the woods with an automatic rifle and a brace of hand-whittled spears. Fritz Matthews is an adequate foil for him as Lieutenant Thornton, and David Campbellís Hogan is suitably slimy. Only the women are complete wastes of space, and their roles are pretty much just plot devices anyway. Even at their worst, thoughó hell, maybe even especially at their worstó these vehemently unschooled performances are crucial to the ďfever dream on filmĒ quality that makes Deadly Prey so much more enjoyable than many cheap 80ís action flicks that are technically far superior.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact