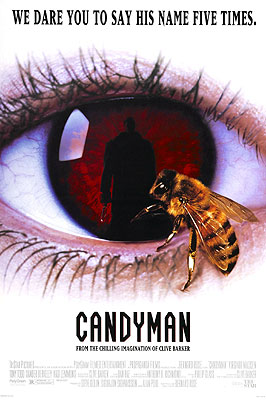

Candyman (1992) **½

Candyman (1992) **½

There is a smallish tradition in 20th-century horror fiction, not much celebrated or even remarked upon, which has nevertheless been a favorite of mine ever since I stumbled onto it in my teen years. Indeed, I suspect the fact that I had to stumble onto it goes some way toward explaining my outsized affection for it, since that’s always made it feel like my own personal discovery. These stories posit that industrial-age cities possess a numen as real and as powerful as any in the natural world, capable with time of giving rise to spirit beings functionally equivalent to minor pagan deities. Furthermore, these emergent divinities of factory, railway, and apartment tower reflect the character of the environment that spawned them, as do the older gods of the harvest, or the truly ancient gods of the wilderness. Like the modern city itself, they make onerous and often terrible demands of the humans living under their power, but can’t be trusted to grant any boons in return beyond another day’s bare survival. Fritz Leiber’s “Smoke Ghost” and Harlan Ellison’s “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs” are both superb examples of the form, but the first one I read, and the one that I still hold dearest, is Clive Barker’s “The Forbidden,” from the fifth volume of his Books of Blood (published in the US as In the Flesh). “The Forbidden” also enjoys the distinction of being among the few tales within this mini-genre to receive high-profile cinematic adaptation. Unfortunately, the first film version was made in 1992, when it was all but inevitable that Barker’s personification of urban violence and the fear of same would be reduced to a mere supernatural slasher.

Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen, of Dune and The Prophecy) and Bernadette Walsh (Kasi Lemmons, from Hard Target and The Silence of the Lambs) are graduate students at the University of Illinois’s Chicago campus, doing research for a thesis on urban folklore. Helen in particular is intrigued by stories of a local spook called the Candyman, who merges two of the common archetypes. On the one hand, he’s said to be the ghost of one of those hook-handed maniacs beloved of campfire storytellers nationwide, but he employs the methodology of the even more formidable Bloody Mary, manifesting whenever anyone is fool enough to chant his name five times before a mirror. (I confess that I’ve never understood how the latter type of boogeyman took such a powerful hold on the popular imagination. After all, it’s so easy to just not do the thing that calls them forth!) The main source from which Lyle and Walsh are collecting their lore is that inexhaustible pool of master’s thesis lab rats, their institution’s incoming freshman class, but while Helen is transcribing the day’s interviews one evening, she discovers that at least two members of the university’s janitorial and housekeeping staff have heard of the Candyman, too. What’s more, these women (Barbara Alston and Doppelganger’s Sarina C. Grant) associate him with a real, documented murder in the blighted Cabrini-Green housing project where they live. That gives Helen the idea that she might actually have run one of her ever-elusive tales to earth, and she convinces Bernadette that an investigatory visit to Cabrini-Green is in order.

It’s something of a double-edged sword that practically everyone who sees the two unfamiliar women— one of them white!— prowling around the projects immediately mistakes them for police detectives. On the upside, it means that the gang-bangers who might otherwise be inclined to rob and/or rape them keep their distance, doing no worse than to taunt and make nebulously threatening gestures at them from no nearer than just beyond arm’s length. It also means that barely anybody thinks anything of it when they illegally enter the still-abandoned unit where the crime they’ve come to investigate took place. On the downside, though, hardly anyone in Cabrini-Green is willing to talk to a cop, so Helen and Bernadette seem unlikely to gather further testimony about what happened there, or about the odd things Helen finds in the even more thoroughly ruined flat next door. Luckily for them, a young single mother named Anne-Marie McCoy (Vanessa Williams, from Thriller and Ice Spiders) proves unusually bold. Anne-Marie confronts the two strangers when she notices them snooping around an apartment that she knows perfectly well doesn’t belong to either of them, but ends up inviting the researchers back to her place after they convince her they’re harmless. Better still, it happens that Anne-Marie was one of those who called 911 when she heard the screaming in the murder flat, and she corroborates the appalling detail that no cops ever came in response until the next day, when there was nothing left to be done but to dispose of the body. She also volunteers that the murder which so many of her neighbors attribute to the Candyman wasn’t even particularly unusual around here. However, Anne-Marie has no insight to offer regarding the strangest thing Helen saw in the second abandoned apartment: the unsettling mural of a giant human face which some Rembrandt of the spray-can constructed around a vaguely mouth-like hole hacked through one of the interior walls. We might infer whom that painting was supposed to depict, though, from bundle of chocolates and razorblades which somebody had left in front of it like some twisted votive offering.

Soon thereafter, Helen and Bernadette have dinner with their respective husbands and a few of Trevor Lyle’s friends from the university faculty. (Trevor is played by Xander Berkeley, of Deadly Dreams and Terminator 2: Judgment Day.) Among the latter is an insufferably pompous professor named Purcell (Michael Collins, from Cold and Dead and Dorian Gray), who not only is acquainted with the Candyman legend, but wrote a paper on it himself ten years ago. Although he does so in the most obnoxious way possible, Purcell provides Helen and Bernadette with quite a bit of Candyman lore which they had yet to dig up on their own. According to the most detailed versions of the story, first recorded in 1890, the Candyman was both an artist and the son of a former slave turned shoe manufacturer, who settled in Chicago during the Great Migration. He was murdered after he got a little too friendly with a white girl whose land-magnate father had hired him to paint her portrait. The lynch mob that did the dirty work sawed off his right hand— his painting hand— and then goaded the bees from a nearby apiary into stinging him to death. Then they burned the corpse, and scattered the ashes over the land where Cabrini-Green stands today.

That enticing new information is nearly Helen’s undoing, for it drives her to return to the projects alone in the hope of uncovering the link between Purcell’s century-old lynching and Anne-Marie’s lethal present-day home invasion. The foolhardy venture seems to go well for her at first, insofar as she befriends a young truant called Jake (DeJuan Guy) who not only knows about another purported Candyman murder, but is able to point her to the dilapidated public toilet where he says it occurred. The trouble is, Helen has rather seriously misunderstood what the people of Cabrini-Green have been telling her. Their Candyman is no spook, but the leader of a drug-dealing gang called the Overlords (Return of the Living Dead, Part II’s Terrence Riggins), who has adopted the legendary figure as the basis for his own personal brand. Lyle is just lucky Candyman uses the blunt backward loop of his signature meathook when he beats her to a bloody pulp after hearing that some white lady has been coming around asking about him.

Some good does come of the incident, though, because the Chicago Police Department isn’t going to let a brutal assault on a University of Illinois grad student slide, even if it happens in Cabrini-Green. And unlike the poor stiffs who have to live there, Helen Lyle has no reason to fear reprisal from Candyman’s gang if she presses charges against him or testifies at his trial. Furthermore, it turns out that Detective Valento (Gilbert Lewis, from Grave Secrets and Gordon’s War) has been watching this particular creep for a long time, just waiting for him to fuck up this big. We don’t get to see what else Valento manages to pin on him at last, but under the circumstances, the charges seem likely to include at least a couple of the murders Helen heard about from Anne-Marie, Jake, and the cleaning ladies at school. If you ask me, the motherfucker’s going to be down in Joliet for a long, long time.

And that, perversely, actually is Helen’s undoing. That’s because in addition to being “real,” the Candyman is also, you know, real. With the flesh-and-blood Candyman behind bars, belief in his rumors-and-ectoplasm counterpart (Tony Todd, from Night of the Living Dead and The Crow) is in danger of waning— and since belief is what keeps him alive, for lack of a better word, that’s not a state of affairs that the true Candyman can allow to persist. The first time this Candyman appears to Helen, he offers her a chance to do things the easy way. If she will volunteer to be his next victim (which she knows how to do from the freshmen’s stories), he’ll make her death as fast and as painless as possible given his public’s expectation that it also be spectacularly gruesome. Then she’ll get to enjoy the same form of immortality as the Candyman himself, her tale told and retold whenever and wherever the superstitious gather to scare each other.

Helen doesn’t go for that, unsurprisingly, so it’ll have to be the hard way for her instead. The next thing she knows, she’s emerging from a blackout in Anne-Marie’s apartment, soaked to the skin in the blood of the other woman’s decapitated dog, and the lady of the house is not a bit happy to see her. Worse still, Anne-Marie’s baby is missing from his crib. Helen is the obvious suspect, and she can’t even explain how she got into the flat in the first place, let alone how little Anthony might have gotten out of it. Detective Valento looks at Helen very differently the next time he sees her— and you can bet he won’t be in any mood to hear about hook-handed ghosts trying to frame her! At least Trevor seems supportive (even if he does take a suspiciously long time to bail his wife out of jail), but he changes his tune after the Candyman butchers Bernadette in the Lyles’ own living room, rigging the scene to implicate Helen once again. Nor is the undead killer finished with Helen even after Trevor has her committed to a mental hospital. Since she refused to shore up his congregation’s wavering belief in him by becoming his victim, he’s now determined to turn her into a monster of legend like himself.

In Clive Barker’s telling, the Candyman was never a human being. Indeed, Barker’s Candyman isn’t even the subject of any particular urban legend. Instead, he’s something like the embodiment of all urban legends, and although he exists in the realm of rumor and anecdote, the key features of the tales that give him life are their vagueness and untraceability. The Candyman’s sacrament may be the telling of stories about senseless, horrid violence, but they must always be accounts of things supposed to have happened somewhere else, to people not directly known to the teller. To speak of the Candyman directly, to acknowledge his existence to anyone not already a believer, is a sin that must be expiated with bloody death. As for Helen, she runs afoul of the Candyman because her study of urban graffiti (not urban legends) leads her to discover one of his sacred places, and subsequently to get too close to the facts of one of “his” stories. Her investigations threaten to specify the Candyman, and therefore to limit him, so he comes forth to steer her into becoming the nameless victim-protagonist of a new tale of bad-neighborhood horror. (You know those council flats off Spector Street? Well, I heard that when they were clearing away the leftovers from the Guy Fawkes Night bonfire last year, they found a woman’s burned-up skeleton in there! Nobody even knows who she was…)

That’s obviously a very different proposition from what writer/director Bernard Rose gives us in Candyman, but the film might actually have been better if he’d diverged even further from the source material. Candyman is shakiest when it hews closest to “The Forbidden,” especially as regards the portrayal of the title character. Somewhat like the Cenobites of The Hellbound Heart, Barker’s Candyman espouses a value system in which unspeakable suffering is an experience to be savored, mortal life is an irrelevancy to be despised, and humanity as we understand it is an infancy to be outgrown at the earliest opportunity. That’s a perfectly reasonable perspective for the new god of urban blight to adopt, but for the ghost of a man, it makes sense only as a lesson learned in the transition to the afterlife. The trouble with Rose’s Candyman is that his outlook is as alien as that of Barker’s, even though he has the experience of mortality to compare his current condition against. Even when he attempts, for reasons that are not clear at first, to reassure Helen that it won’t be as bad as she fears to die horribly in order to be reborn as a personified story about horrible death, he shows no sign of appreciating what he’s requiring her to give up. He shows no sign of remembering the terror that his own human self must have felt as first the lynch mob and then the bees went to work on him, or the attachment that he must formerly have had to his material existence and everything that went with it. A being that has never known mortal life can plausibly scoff at it, but a ghost ought to know what it means to those who have it, even if the ghost in question considers undeath the better deal upon informed comparison. Rose must have sensed that something in the killer’s characterization was out of whack, too, because he supplements his approximation of the Candyman’s original reason for pursuing Helen with a new, utterly human motive, springing the latter on us as part of a twist ending. That actually makes matters worse, though, because it throws the incoherency of the revised Candyman into even starker relief. If the Candyman is still man enough to be susceptible to the tiresome old “reincarnated love” routine, then surely he’s also man enough to grasp how unappealing his form of immortality is apt to look to somebody who hasn’t been living it for more than a century.

There’s also a second major inconsistency in Rose’s portrayal of the Candyman, concerning how he relates to, and is related to by, the residents of Cabrini-Green. The idol-like mural in the ruined apartment and the votive offering of bonbons and razorblades comes straight out of “The Forbidden,” in which they serve as the first harbinger of the dark magic that Helen has accidentally uncovered. Again, idols and offerings are trappings appropriate to a god, but seem rather less fitting for a mere ghost. Furthermore, their presence in Cabrini-Green specifically flies in the face of the fakeout involving Candyman the drug-dealer. Pay close attention during the first act, and you’ll see that nobody from Cabrini-Green— not Anne-Marie, not Jake, not the University of Illinois cleaning ladies— ever says a word to imply anything supernatural about Candyman. Once he and the Overlords corner Helen in that bathroom, it should therefore snap into place that here in the hood, “Candyman” is merely the name of a common criminal. The people of Cabrini-Green all have way too many real-world problems to waste precious give-a-fucks on a sack of angry bees with a hook for a hand who hangs out in mirrors and cuts up dumbasses who won’t stop saying his name. If Rose’s Candyman has a congregation of believers, they’re the suburban white kids from whom Helen and Bernadette were harvesting their thesis data before the cleaners inadvertently sent them off on a wild goose chase after Cabrini-Green’s deadliest gang-banger. His shrine should be hidden under an overpass in Evanston, not in the bedroom of an uninhabitable upper-story unit in the projects. So what imaginable impact can it have on the belief that sustains the true Candyman’s existence when a bunch of people who show little sign of having believed in him in the first place no longer have to worry about getting murdered in their own homes by some asshole who appropriated his name in approximately the same way that I appropriated the name of a Mexican wrestling star of the 60’s and 70’s?

But although Candyman is a misfire as an adaptation of “The Forbidden,” it’s often pretty damned good when it ignores the source story completely and goes off in its own direction. Most notably, Candyman is one of the most overtly and incisively political horror films of its era, and easily the most socially conscious slasher flick since the 70’s. The movie’s most powerful and effective innovations follow naturally from the change of setting from 1980’s Liverpool (a white-as-fuck city where poverty was white as fuck, too) to 1990’s Chicago (an exceedingly diverse city, but also one of the most racially segregated in the northeastern quadrant of the country— with all the ills and injustices that such segregation usually implies in the United States). Once you’ve transferred a story set among the urban poor to the Northern field headquarters of institutional racism, it would be downright irresponsible not to address those realities, no matter how fantastical the core premise might be. Commendably, Rose never shies away from touching any of the perennially raw nerves exposed by his treatment of the tale. His version of the Candyman comes to stand in for all the thousand ways that life in America remains rigged against its black citizens. Affluent, educated, and possessed of a talent that even the wealthiest and most powerful of white men had to recognize, he still wound up the victim of brutal racist violence, and the territory he now haunts is a monument to his people’s continued degradation. Helen’s research into the murders at Cabrini-Green incidentally reveals that the luxury highrise where she and Trevor live had also been built as low-income public housing, but was hastily upgraded and privatized when the residents of the surrounding upscale neighborhoods complained to the city government. Official neglect is a recurring theme of all Helen’s conversations with the inhabitants of the projects, and the film explicitly acknowledges that her race and class make all the difference between the police department’s handling of the human Candyman’s attack on her and its effective refusal to handle any of his countless previous crimes. And while part of me wants to say that Anne-Marie’s opening salvo about Helen and Bernadette’s motives is a little too on-the-nose, I think maybe the average white viewer needs to hear her suspicions of the researchers spelled out this bluntly. (Intriguingly, Anne-Marie seems to include the light-skinned but nevertheless black Bernadette when she talks about what “white folks” do on those rare occasions when they show their faces around Cabrini-Green.) It’s possible to object to the ways in which Rose chose to explore the racial and class issues informing Candyman, to be sure. After all, Helen, the well-off white woman, is the viewpoint character here, and a certain amount of exoticism toward the black and poor inescapably follows from that. But at the same time, I’m not sure a white Hollywood filmmaker could plausibly do otherwise anyway.

Rose also deserves props simply for operating so far outside the usual boundaries of the supernatural slasher formula here. It’s weird enough that the true Candyman never shows his hand until the movie is roughly half over, and that the nightmarish murders in Cabrini-Green aren’t even his doing, but what really makes this movie stand out from the pack is the nature of the threat he poses toward Helen. Yes, the Candyman intends to kill her, just as you’d expect. But he either can’t or at least won’t do so without her permission, and so in the meantime he makes it look like she’s a serial murderer by repeatedly killing people with whom Helen comes into contact. It’s a bit like what John Ryder does to Jim Halsey in The Hitcher, although the Candyman’s ultimate objective is of course very different. And that unusual ultimate objective in turn means that Candyman’s version of the “Whoops… Looks like evil triumphs after all” stinger that came standard with latter-day slasher flicks is like no other I’ve seen. However much there is about Candyman that quite simply doesn’t work, it has enough going for it, too, to justify its position as a minor landmark of early-90’s horror.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact