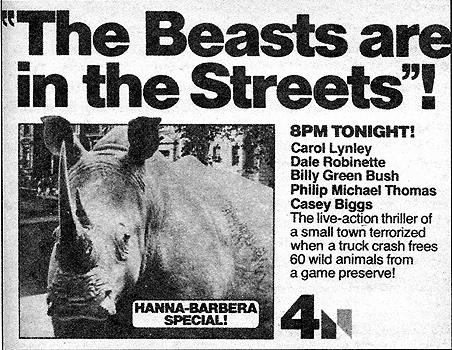

The Beasts Are on the Streets / The Beasts Are in the Streets (1978) -**½

The Beasts Are on the Streets / The Beasts Are in the Streets (1978) -**½

Do you remember me saying, in my review of Kingdom of the Spiders, that one of the principal lineages of animal attack movies was essentially a mutant form of disaster film, in which killer critters stood in for a burning building, a capsized ship, or an airliner whose pilot ate the salmon for dinner? Well, The Beasts Are on the Streets is a textbook example of that form, right down to its habit of paying more attention to its several concurrent family soap operas than to its rampaging lions, tigers, and bears. At the same time, though, it’s also a very weird example. For one thing, it gets started with almost unparalleled efficiency, knocking down the fence around the African Wildlife safari park before the first commercial break, and shortchanging in the process the setup for its interpersonal drama. And precisely because it was made for television, The Beasts Are on the Streets had no money for the cavalcade of slumming stars that was virtually de rigueur for disaster flicks even on the small screen; a 1978 TV budget would cover live rhinos and ostriches or a star-studded cast, but not both. Then there are the tonal peculiarities arising from the collision between the bleak mood of the 70’s and the vapidly sunny brand identity of Hanna-Barbera, which produced the film as part of an effort to expand beyond their accustomed niche as purveyors of the world’s shittiest cartoons. But what might be strangest of all is that two of the aforementioned family soap operas play out among the rampaging animals, as a camel gives birth to a sickly calf, and one of the lionesses searches high and low for her missing cub!

African Wildlife is a fictionalized version of the now-defunct Lion Country Safari theme park in Grand Prairie, Texas. Visitors to African Wildlife are taken on ranger-hosted trolley rides through the park, which is mostly one giant, free-range enclosure for animals of the veldt: antelopes, zebras, leopards, ostriches, rhinos, elephants, and of course a pride of lions led by a famously fecund male called Renaldo, who is said to have sired some 250 cubs over the years. Mind you, the park also has dromedary camels, which didn’t live on the veldt even before their wild ancestors went extinct, along with tigers and grizzly bears, which aren’t found anywhere in Africa outside of a zoo. Obviously there are situations in which Mr. Sherman (Carter Mullally Jr.), the do-gooding conservationist entrepreneur in charge of the whole operation, lets showmanship win out over educational intent. Most of the film’s major characters are affiliated with African Wildlife in some way. Kevin Johnson (Dale Robinette), Eddie Morgan (Philip Michael Thomas, from Black Fist and The Dark), and Rick Andrews (Casey Biggs) are all rangers. Dr. Claire McCauley (Carol Lynley, of The Night Stalker and The Shuttered Room) is the lead veterinarian. And Sandy McCauley (Michelle Walling) is Claire’s tween daughter, who fervently wishes Mom would quit beating around the bush, and marry Kevin already.

We wouldn’t really have a movie, though, with just that bunch and their quotidian-ass problems, so permit me to introduce Jim Scudder (Billy Green Bush, of Unholy Matrimony and Critters) and Al Loring (Burton Gilliam, from The Terror Within II and The Fanglys). These two drunken, snake-mean cretins are driving home from a successful buck hunt when we meet them, swerving all over the road like a couple of goddamned maniacs, taking potshots at signs and billboards as they rush past, and generally making a public nuisance of themselves all up and down Interstate 30. Among the fellow drivers whom they menace is a long-haul trucker (Bill Thurman, of Zontar, the Thing from Venus and Night Fright) lugging a 53-foot tank trailer full of gasoline. Exactly the sort of vehicle you most want to cut off while changing lanes, right? Worse yet, the trucker has a weak heart, so throwing a scare into him is a great way to cause a disaster fit to become above-the-fold front-page news in all the regional papers. In a bizarre inversion of Duel, Jim and Al take it upon themselves to become this poor guy’s nemeses, culminating in Jim hanging out the passenger side window of their station wagon to brandish a rifle at him! Inevitably, the trucker succumbs to a heart attack right alongside the African Wildlife perimeter fence. He loses control of the truck, runs off the road, and demolishes several hundred yards of fencing before the cumulative impact of all those posts and all that wire mesh brings the vehicle to a stop— at which point the rig rolls over and erupts into a massive fireball. The explosion panics every animal within earshot, and the next thing you know, the whole menagerie from gazelles to elephants has poured out onto I-30, and thence into every corner of Grand Prairie.

Obviously the park staff have a job of work ahead of them, rounding up all those animals. And just as obviously, the people of Grand Prairie are due for an exciting week, as bears crash birthday parties, elephants go on late-night strolls through the richest neighborhood in town, and big cats of every description acquire a taste for household pets. Johnson and his fellow rangers will face a second front in the struggle, too, as the local police do everything in their power to make the situation worse under the leadership of a lieutenant (Play Dead’s Robert Hibbard) twice as aggressive as the tigers and half as smart as the zebras. Then of course there are all the townspeople putting themselves up for Darwin Awards by trying to help— by lassoing ostriches, or giving bowls of milk to lion cubs, or heaven knows what other well-intentioned tomfoolery. The most serious complication, however, arises when Jim Scudder gets in on the action once again, for his tomfoolery isn’t well-intentioned at all. His head swimming with visions of glory and notions of finally making a man out of his sissy-Mary son (Jeff Bongfeldt), Jim leads Al and the boy out in the dead of night to hunt the lions that struck the Scudder homestead earlier, killing the family dog. And as if that weren’t sufficiently suicidal already, Jim bundles up for the hunt in a buckskin coat exactly the same color as a lion’s fur.

I’ve been able to dig up frustratingly little information on Hanna-Barbera’s live-action experiment. I can tell you that it spanned most of the 1970’s, and persisted a little ways into the 80’s as well— but the low volume of its output suggests that the project was not a great success despite its relative longevity. Hanna-Barbera produced both TV series and movies in live action during this period, with the latter seeming mostly to have been made for ABC to broadcast as part of its “Movie of the Week” and “Afterschool Special” programs. And most of the live-action H-B telefilms that I’ve uncovered sound about like what you’d expect when the studio responsible for Hong Kong Phooey and the Great Grape Ape tries to stretch its wings: a weary Western here, a dismal superhero team-up there, a Christmas special that could have been a 30th-percentile episode of “The Wonderful World of Disney” over thataway. But The Beasts Are on the Streets, so far as I can determine, was one of kind.

I don’t mean that just among its Hanna-Barbera stablemates, either. For better and for worse, I can’t think of another animal attack movie or disaster film much resembling this one once you dig into the details. A large share of The Beasts Are on the Streets’ uniqueness is a direct result of its cheapness, too, which pushed the film in some unexpected directions. As I said before, producer Joseph Barbera decided to spend the money on lots and lots of animals and their handlers, automatically ruling out the typical disaster movie all-star cast. I mean, how often did Carol Lynley and Billy Green Bush get to be the big names? Even Philip Michael Thomas was pretty much nobody at this point in his career, six years before “Miami Vice.” The disadvantages of such a William Girdler-style cast are obvious, but the makers of this movie found a hidden upside. If you can’t afford famous has-beens to cameo as victims, then why not put the handlers and trainers themselves in front of the camera to do things with the animals that any mere actor would have to be out of their mind to attempt? The attack sequences involve a shocking amount of hands-on roughhousing with exceedingly dangerous creatures, making up for the film’s censor-imposed mildness in other respects. We get tiger wrestling, ostrich racing, and, in what must surely be the most hazardous animal interaction of all, even a bunch of yahoos off-roading in a suped-up Volkswagen Beetle getting chased by a rhinoceros. (Those fat bastards can run at over 30 miles per hour, and wouldn’t have the slightest trouble flipping a VW stripped of every bit of nonessential weight. Definitely do not try this at home!) And as an interesting collateral result, the world of The Beasts Are on the Streets ends up being much less heavily populated by beautiful people than I’m used to seeing even on 1970’s TV, where guys who looked like George Kennedy could still get regular work. One doesn’t hire a grizzly wrangler for his glamorous appearance, after all.

This movie’s other abnormalities are not so easily explained, however. Given how badly writers Frederick Louis Fox and Laurence Heath want us to become invested in trivialities like whether or not Kevin Johnson will ever succeed in penetrating the elaborate security measures surrounding Claire McCauley’s heart, it’s odd that they’d allow themselves only enough time to establish that there’s no evident reason to like either one of them before setting the main plot in motion. And it’s even screwier that they try turning Jim Scudder into the focus of a redemption subplot only after making it perfectly clear that the best and surest tool to fix what’s wrong with him is the jaws of a hungry lion. Then there are Eddie’s and Rick’s individualized subplots (Will Eddie get that longed-for promotion? Can Rick find his way into the cute receptionist’s pants despite her repeatedly dismissing him as an uninteresting cad?), which are left to wither on the vine. Let’s not forget, either, about the sick baby camel or the lioness on the hunt for her cub. The former feels like a few pages from an “All Creatures Great and Small” script got stapled into the teleplay by mistake, while the latter suggests a complete alternate version of The Beasts Are on the Streets that got shitcanned in favor of the one that Hanna-Barbera actually made.

My favorite thing about this movie, though, is its ultimate inability to reconcile the demands of its genre with the instincts of its creators. When I learned that The Beasts Are on the Streets was a Hanna-Barbera production, my mind leapt immediately to Yogi Bear and Booboo breaking containment to plunder a small Texas town of its picnic baskets, but the only scene that comes anywhere close to such a mood is the one in which a team of African Wildlife rangers must ring the callbox outside a snobby old rich lady’s security fence in the middle of the night to inform her that she has elephants on her property. Otherwise, we have here a good-faith effort to take seriously the threat posed by several score captive, but by no means tamed or domesticated, animals running loose in a populated area— or at any rate, we have that most of the time. The filmmakers aren’t afraid to let bad things happen, even if they wind up being not quite as bad in the end as they might have. But because Hanna-Barbera can’t quite shake the habits of kid-vid, the lion cub’s adventures need to be part of the climax, and the means whereby they get folded in are downright insane. The little guy intrudes himself into the operating room where a team of surgeons is scrambling to patch up Jim Scudder’s son (didn’t I tell you that nighttime lion hunt was a bad idea?), with Kevin Johnson, Mama Lioness, and Jim himself all showing up in hot pursuit at the same time! How often do you see a movie paint itself into such an inescapable genre-expectation corner that it has to pull something like that in the hope of getting out?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact